In Lagos’s Mile 12 market, a tomato seller begins her day before sunrise. Like many women who run informal businesses across Nigeria’s open markets, her daily earnings depend not just on how much she sells but on how stable her operating costs and access to basic financial services are.

Her story is reflected in national data that shows how women traders hold a large part of the informal economy but remain on the lowest rung of its financial ladder.

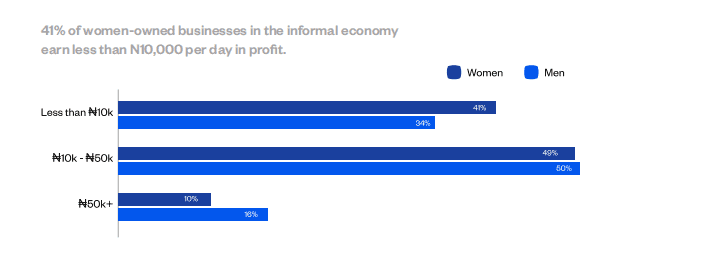

According to the 2025 Informal Economy Report by Moniepoint, women own 35% of businesses in Nigeria’s informal sector. The report shows that 41% of these women-owned businesses earn less than ₦10,000 in profit daily compared to 34% of male-owned businesses.

At the other end, only 10% of women-owned businesses make more than ₦50,000 per day, while 16% of male-owned businesses reach that profit level. This earnings gap means most women traders operate with narrow margins and little room for reinvestment or business expansion.

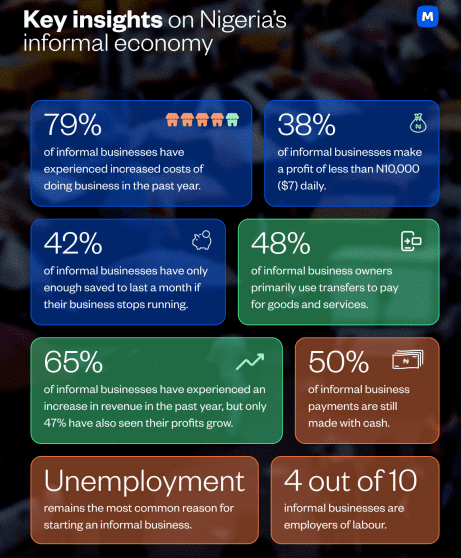

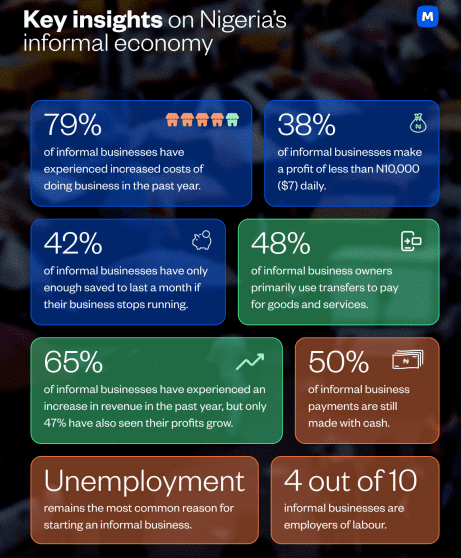

These numbers speak to a broader story about the structure of Nigeria’s informal economy. Women dominate visible retail trade, selling food, produce, household goods and daily essentials in local markets across the country. But ownership does not translate to financial power.

Most women traders operate on thin profit margins and are locked out of the systems that could give them leverage. Their daily earnings are quickly eroded by operational costs, unstable prices, and levies. Their businesses are visible, yet their economic agency remains limited.

An informal business by a woman is unlikely to receive a higher loan

The gender disparity extends to access to finance. Only 6% of women in the informal sector have received loans above ₦1 million, while men are twice as likely to access larger credit.

This limits their ability to scale. A woman trader selling foodstuffs in Oshodi or Aba often relies on what she can save from the day’s sales to restock. If she gets credit, it is usually from friends, cooperative savings groups or informal lenders, many of which charge high interest rates or require social guarantees. Formal banks remain out of reach for most.

The report notes that women traders mostly rely on cooperative savings schemes to keep their businesses afloat. 74% of informal business owners say they save regularly, and a majority of the women use informal savings groups such as ajo and esusu to do so.

These systems provide some liquidity but do not offer the flexibility or capital required for meaningful business growth. A woman who saves ₦500 or ₦1,000 daily over the course of a month can use that to restock or manage family expenses, but the amount is rarely enough to expand her business or invest in new tools.

Another pressure point is the daily levy structure that many market traders face. Nearly one in two informal businesses pays some form of levy or tax. A trader paying ₦500 every day in market dues ends up spending about ₦125,000 each year.

This is more than what many small traders invest in stock at once, meaning that a significant share of their income is going to daily operational costs they cannot avoid.

Unlike formal taxes that might come with some form of documentation or benefits, these daily levies are usually collected informally through market associations or local authorities.

The burden is particularly heavy on women because of their concentration in retail and food trade. These are low-margin businesses that require daily liquidity to operate. Inflation makes this worse. When the price of tomatoes or garri spikes, the woman trader bears the brunt. She may sell less, earn less, and still pay the same levies.

The 2025 Informal Economy Report also highlights that women traders are less likely to have formal business registration, less likely to receive credit from formal financial institutions, and less likely to own the stalls they trade from.

This lack of formal assets makes it harder to use their businesses as collateral for loans, locking many into subsistence-level operations. It also means they are excluded from many financial support schemes that require documentation or collateral.

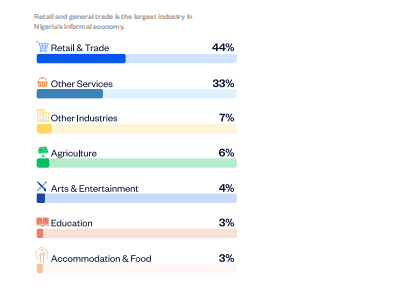

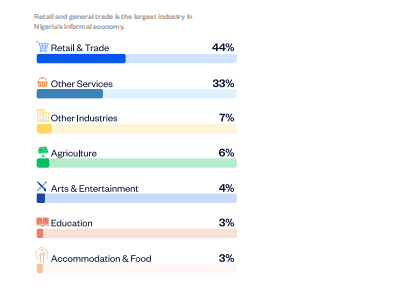

This exclusion is happening despite the size and influence of the informal economy. The report points out that a significant portion of daily transaction volume in Nigeria is generated by informal businesses, particularly in retail and food trade, where women dominate.

There is also a trust issue at play. Many women traders remain sceptical of formal banking services because of past experiences with hidden charges, delays, or inaccessible requirements. As a result, they prefer to operate with what they can control.

But this preference also limits their ability to build credit histories, access insurance, or benefit from government-backed financing programs.

The report concludes that women traders remain central to the functioning of Nigeria’s informal economy but are excluded from the structures that could help them grow. They drive daily transaction volumes, feed local economies, and sustain entire communities, yet they absorb the highest costs with the least security.