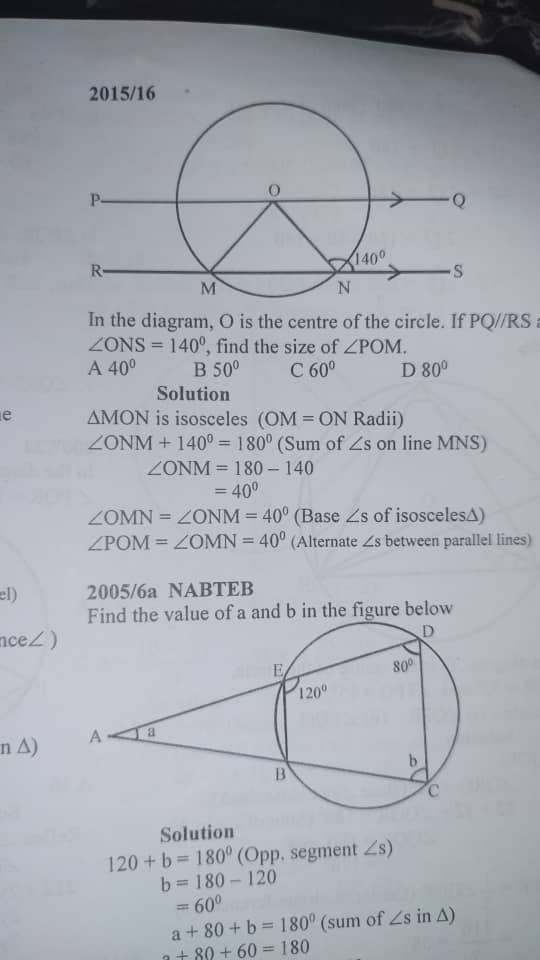

As one of the best network monitoring tools in the world, Wireshark is used by hackers and sysadmins alike to capture and analyze network packets across a myriad of situations for troubleshooting and logging.

As we’ll discover, it was also one of the earlier open source projects to cross the then prickly divide between Linux and Windows.

We talk to Gerald Combs and Loris Degioanni about how the project started and developed, and to discover more about their latest systemwide analysis tool, Stratoshark.

Linux Format talks to Gerald Combs and Loris Degioanni, about creating Wireshark, the origins of network packet analysis, and how they want their shark to fly...

This article was originally published in Linux Format magazine.

Linux Format: It’s nice to know people’s background, so what was your first experience with computers and how did you get involved with Linux and open source?

Gerald Combs: My first experience with a computer? I’m gonna be giving away my age here… My parents bought me a Timex Sinclair 1000 (the US ZX81 model), which was this tiny, very inexpensive, minimum viable computer. That’s what got me hooked. What got me into networking, I was studying computer science, took a networking class, and I got hooked from there.

At the same time as attending classes, I was working in the computing services department, and part of my job was to troubleshoot the network. They gave me this network sniffer. It was this device that weighed quite a bit. It cost as much as a luxury car, and I got to lug it around campus and plug it into different parts of the network and do troubleshooting.

After that I took a job at a small ISP that couldn’t afford a sniffer. It just didn’t have the budget for it and that’s what gave me the impetus to start writing a protocol analyzer. At this point, luckily, the PCAP library that lets you do packet capture had been released, so it was easy to plug into that.

Suddenly I had this analyzer and released it to the public. I released it as open source because at that time, I had used quite a bit of open source software and it just seemed like a really good way to give back to the community. As it turned out, this was a great move, because releasing it as open source let a whole bunch of people contribute, and that’s where we got our initial developer base. The project also just grew from there. We got a really big boost in our user community when we added in support for WinPCAP, which is kind of where Loris joins in. This let us expand our user base to Windows users, and suddenly we have this explosion of users and this large community.

Loris Degioanni: My first computer was a Commodore 64 – I’m old as well! The computer where I actually learned a lot of stuff and that made me a programmer was an Amiga. I was 14 or 15, and I got a summer job as a bartender in Italy. I got enough money saved to buy myself either a computer or a scooter. Everybody in Italy at that time wanted a scooter, and all my friends were buying them. I decided to buy the computer because I was so passionate about that, and that’s where I started programming. So, that’s what got me into operating systems and Linux.

From the very early days, I remember installing Slackware on my 486 with a tower of floppies, and going and using some of my savings to buy 60MB of RAM for my 486, so I could run X Window. Otherwise I could only run Linux on the command line. Those were the days when I was at university, I was studying computer science, really getting into software, and having access to an operating system where you had the source code and you could compile the kernel and study how it works and so on. And there was active development, and being able to contribute was so powerful and fascinating for me.

My story at the university continued with me getting passionate about networks, a little bit like Gerald, and I started working with a computer networking group at my university in northern Italy. As Gerald has mentioned, network analyzers were extremely expensive and were not really accessible. Very often, they were pieces of hardware, like suitcases, that you had to take around our computer networks. The professor thought that the best way to learn networks was to observe them and see what’s happening, see the packets go back and forth.

The problem is, we absolutely couldn’t afford to give a network analyzer to all of the students in the lab. And the other problem was that the labs at that point were running Windows. So, I got the project of hacking with the kernel of Windows to try to make a package capture library similar to the ones that were available for Unix and Linux. That was the first serious software project I did. While doing that, I also ported tcpdump to Windows.

I put all this stuff on the little server under the desk. By the time I graduated, that little computer under the desk was doing more traffic than the rest of the university combined.

And that’s how WinPCAP was born, and essentially it was the success of two people, me in Italy and Gerald in the United States. We’d never met in person, but we created two things that were complementary. He created the user interface part and I created the capture engine for Windows.

Linux Format: Just to whizz back, could you quickly go into a little detail about what packet sniffers are and why you then needed to do your own implementation?

Gerald Combs: As far as the actual network sniffer goes, it was a product of its time. They were trying to address the same problems we were, but they were developing it in the ’80s, versus in the late ’90s, so computers weren’t quite as fast. They had to get as much powerful hardware as they could into as small and portable unit as they could. They were called luggables and were suitcase sized. Maybe they had a CRT.

So, you were not only lugging around a computer, you were also lugging around two pounds of glass as a display tube. The computers weren’t fast, so you had to have special hardware for capture, so that included probably a full-length or half-length capture card with custom chips on it. So, that made it expensive and made it heavy, but it did the job at the time.

It’s just that by the time Loris and I came around, computers were fast, and you had things like Linux, where you could go and hack the kernel pretty easily and add something like LibPCAP, and network cards were cheap.

I should say that where Loris focused on Windows, I was kind of pathologically blind to it, because you asked about Linux experiences. Throughout the ’90s, I used Unix and Linux; that’s what we used at the ISP, and that’s what I focused on. I just had a minimal awareness of the Windows world for however that worked. It was very fortunate that Loris came along, because, that’s how we got our initial really big boost in the user community.

Linux Format: It highlights how important open source can be to people, with students learning and developing knowledge of how these systems work.

Loris Degioanni: Not only that, but I feel that the library I created was one of the first projects, if not the very first, that really bridged the Windows and Unix worlds. One of the reasons why I was saying the server under my desk was generating so much traffic is that I essentially enabled users to run tools that were powerful and popular in the Unix world, such as tcpdump, on Windows.

This was quite radical at that point. The tcpdump port for Windows was called Windump, so a different name. It wasn’t tcpdump for Windows, because the authors of tcpdump didn’t want to tie their name to Windows. In practice, this was quite game changing.

Across the decades, Microsoft had taken many steps to port the full Linux stack and Unix stack, all the tools, the shell, all this kind of stuff, to Windows. At this point, there was still a clear separation, not only technical, but philosophical and politically. This was essentially the first attempt to unite the two worlds and I think it was positive, not just for technical people who could use this tool on Windows, but it was also positive as a way to show a path for the Windows community to embrace open source.

For a while, there was a network analyzer created by Microsoft, that just wanted an alternative. But after a while, our open source tool was just better, more widely embraced by the community. Being open source enables your colleague or your friend to install it, then it’s easy to share information and to work together. So, it enables some workflows that not even Microsoft could enable on its operating system. It showed a path that has been followed by other projects, other companies, including even Microsoft. So, it wasn’t orthodox, but it was cool and exciting to be part of something like that.

Linux Format: You’ve almost answered our next question about developing the community around Wireshark.

Gerald Combs: One of my challenges throughout the entire life of the project has been keeping up with the community. I remember when I made the initial release, I think I started getting contributions the next day, and so early on, especially, it was kind of a struggle to keep up with the community, just because the infrastructure for hosting open source projects wasn’t there.

I had to go build everything myself. I had to go buy, say, a server off eBay, but it was this little Sun workstation, and go find hosting. So, I would trade consulting with ISPs around town, and ask, “Can I put my box here?” and then do that for a few months, and I’d have to go find another friend at another ISP and park my box there. Nowadays, you have GitHub and GitLab, and it’s very easy to plug all that in and just get up and running with an open source project.

I think Loris has mentioned in the past that Wireshark is the perfect open source project, because you can have a whole bunch of people developing protocol analyzers in parallel. If you know a lot about network protocols, typically you know how to write C code as well, at least enough to write a protocol detector for Wireshark. That really helped the project grow as well. You had all these experts from all these different industries going, “Hey, I can add this automotive protocol” or “I can add this telephony protocol,” and they all did at the same time.

Loris Degioanni: And I just want to remind you that especially in the early days, 1998-1999, there wasn’t GitHub, there wasn’t even Git. There was no social media, so even advertising your project was on newsgroups. With development, at least at the beginning, my releases were ZIP files.

It was a different world these very early days, so both from the technical point of view, but also from the community point of view, we sort of had to figure it out. There was a quick evolution during those times, not only on how to develop these tools in the open, but also how to talk to your users, manage your communities, and how to reach out to them, and how to receive their contributions and include them all, including licenses – all this kind of stuff.

Linux Format: So, what were the other main issues you had to overcome?

Gerald Combs: I hate to keep beating on Microsoft, but one of the things that really helped the project was the fact that in the mid-2000s, Wi-Fi was taking off, but it wasn’t quite reliable, not nearly as reliable as it is today. Windows XP had taken off, and we had a lot of users saying, “I’m trying to capture wireless on Windows XP, and it’s just not working.”

At the time, when you tried to capture wireless using the NIC drivers, they just shut the adaptor down, which wasn’t very useful. I got in contact with Loris and asked if there was a way to solve this problem. He’d founded a company here in Davis called CACE Technologies, and we decided that there’s a product to be developed here. Loris offered me a job, and that’s how I ended up moving from the Midwest to California, and in that move, we had to change the name of Ethereal to Wireshark, as my former employer had the trademark for Ethereal. You asked about challenges – getting licensing down, and trademarks down, and IP down has been one of those challenges.

Linux Format: You’re coders – you want to code, you don’t want to worry about legalese.

Loris Degioanni: It was a challenge, but it was also one of the testaments to how powerful open source and communities can be. Essentially, we decided that we wanted to do a company, and we wanted to build products around this network analyzer, and both Gerald and I and our business partner had zero entrepreneurial expertise or experience raising venture capital.

We decided to go rent an office and start building stuff, and doing consultancy to initially pay the bills, but we didn’t have the ability to acquire the assets of Ethereal, to be able to start the company around it. So, we formed the project. We picked a new name, Wireshark, we created a website, and we told the community, “We’re still the same people, but we are changing name.”

We picked the name; using an animal seemed like a great way to have good logos and good mascots. And in fact, you know, that proved to be successful. And the name Wireshark is memorable. Everybody who has done networks now knows Wireshark.

Linux Format: What is it that Wireshark does that’s made it so successful and where does it go next?

Gerald Combs: Wireshark’s job is to take all the packets that go across our network that it can capture and take that data and display it in a way that humans can understand. And it does this through a process called dissection. It takes every field in each of the packets and breaks it down and shows you. What’s the name, what’s the value, what are we looking at here. And that’s why I think it’s so successful, because it lets you see all the packets, it lets you filter them, drill down and do all sorts of analysis. That’s why I’m excited about Stratoshark – the intent is for that to be the same type of tool for system calls.

Loris Degioanni: Gerald and I are launching a new member of the Wireshark family. It’s called Stratoshark, and it applies essentially the same user interface, the same way to see discrete information and be able to drill down and take captures, apply filters and customize the columns, and all of this kind of stuff. But instead of doing it for network traffic, it does it for system calls and system information under Linux.

You can install this on your Linux workstation, a virtual machine, a physical machine, and it supports containers. You click the Capture button, but instead of capturing the network traffic, you essentially see all of the activity that is happening in the machine, the executed processes, all of the files that are open and closed, read and written, all of the network conversations, all of the data process communication.

It’s like an X-ray system that is going to be very familiar for people who are using Wireshark, but it’s a tool for Linux troubleshooting and security investigation, and we gave it a new name: Stratoshark. We’re excited after 25 years to bring a new flavor of Wireshark that is specifically designed and optimized to see inside the inner workings of a Linux machine and be able to troubleshoot at the process and system call level.

Linux Format: This isn’t expanding Wireshark or sitting beside it?

Gerald Combs: It’s a sibling application to Wireshark. It’s its own application that you can download.

Loris Degioanni: When we started working on this, we had a choice: do we just take Wireshark and add this functionality inside Wireshark and there’s a single tool that can do both things, or do we create a sister application that looks a lot like Wireshark, but it’s a separate tool that you can download? We chose the latter because there’s stuff that we wanted to make unique and optimised.

It could have been a bit overwhelming or confusing for users who had to switch between two operating modes. So, this looks like Wireshark, has the same filtering system, the same display system and so on, but there are also things in this tool – for example, the ability to track processes and users, the ability to display data in specific ways – that make it unique. We’re applying the Wireshark philosophy, but creating a new tool.

Gerald Combs: Along with that, when we were deciding whether or not to keep it all in one application or to split it, you have to keep the user experience in mind and what their needs are and how their workflow is going to be affected. If you’re focused on analysing systems, you really want a tool that’s dedicated to that and not have to wade through the huge Wireshark feature set, but if you’re focused on systems, you don’t want to wade through all the telephony and networking stuff!

Linux Format: This sounds as though it’ll have a wide application, are you aiming it at any particular deployments?

Loris Degioanni: The use cases are broad – they can cover anything from running these on your local machine to troubleshoot, system-level troubleshooting and observability to running these on cloud instances to see what your containers are doing, figuring out application issues or analysing an attack, which is another powerful thing that you can do, because Stratoshark is actually integrated in terms of capture analysing with Falco. This is another project Gerald and I have been involved with, which is more like a security camera for modern, containerised infrastructure.

Falco can generate signals, detect when there’s an attack and create the capture, and Stratoshark can analyze the capture. So, there’s actually a broad set of use cases, some which are more for personal use, which I really recommend readers of your magazine try, because it’s just fun and interesting to be able to take a capture of your system. There’s also professional applications for these in security and troubleshooting for modern infrastructures that are running in the cloud or in data centers and so on. The full spectrum of Linux applicability.

3 hours ago

20

3 hours ago

20

English (US) ·

English (US) ·