The recent warning from the World Food Programme (WFP) about rising hunger in Northern Nigeria confirms a reality many of us who study and report on this crisis have been following closely for years. Terrorist attacks and the widening insecurity across the region are now pushing nearly 35 million people towards severe food shortages as the 2026 lean season draws closer.

This figure is not inflated; it reflects conditions that have been building quietly across rural communities where violence, displacement, and economic strain collide every day.

In Borno state, where the Boko Haram conflict began, the situation is even more troubling. I grew up in this region and witnessed the early stages of this war. The estimate that 15,000 people are heading into famine-like conditions is consistent with what local monitors, aid workers, and community leaders have been worried about for months.

When entire villages lose access to farmland because of IEDs, ambushes, and shifting control between ISWAP and JAS, hunger stops being a risk and becomes a certainty.

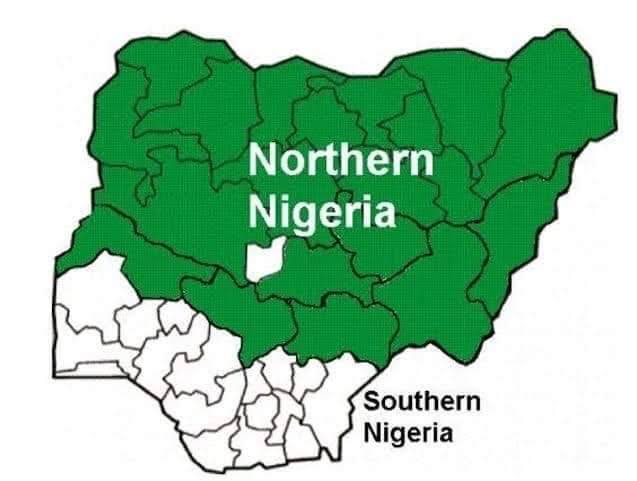

The conflict has already claimed more than 40,000 lives and displaced close to two million people. Yet, the crisis has expanded well beyond the North-east. The spread of armed groups into the North-west and North-central, commonly called “banditry,” although their tactics now resemble insurgent operations, has opened a second front.

The recent mass kidnappings in Niger, Kebbi, and Kwara states are not isolated. They fit a clear pattern of criminal and terror networks blending forces, extending influence, and testing the state’s capacity to respond.

While the war is not as intense as it was in 2015, the pace of attacks has risen sharply this year. From my own fieldwork across Borno, Yobe, Zamfara, and Katsina, it is evident that security agencies are stretched thin.

Reinforcements often arrive late, community warnings go unheeded, and local vigilante groups that once helped stabilise villages are now worn out or deliberately targeted.

Economic hardship is adding more pressure. The lean season has always been difficult, but inflation has stripped families of the little safety net they once relied on. In many rural towns, the cost of staple grains has more than doubled, forcing households to depend on aid that is itself shrinking.

The WFP’s reduced capacity is already visible on the ground. Nearly a million people rely on their support in the northeast, yet funding cuts have shut down hundreds of nutrition centres.

In Jibia, Damasak, Zurmi, and Sabon Birni, families now walk long distances seeking help, only to find that the nearest facilities have closed. When a fragile system loses a third of its capacity, a surge from “serious” to “critical” malnutrition is the natural outcome.

The growing presence of jihadist groups adds another layer of concern. The recent claim by JNIM, a group rooted in the Sahel, marks a troubling shift. Their operations reaching into Nigeria suggest the slow merging of the Sahel and Lake Chad conflict zones, an escalation regional analysts have anticipated for years.

The situation described by the WFP matches what communities across the North have been living through daily: shrinking farmland, repeated attacks, volatile markets, and aid pipelines drying up just when they are needed most. People who once showed remarkable resilience are now reaching breaking point.

As 2026 approaches, the humanitarian outlook is shaping into one of the hardest seasons since this conflict began. The numbers tell part of the story, but those of us from these areas have seen how hunger takes hold long before the statistics reflect it. The warning is credible, and it deserves urgent attention.