1

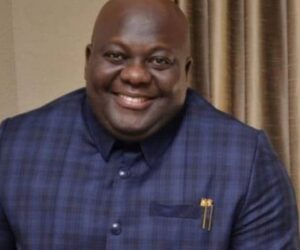

There are moments in a democracy when the truth must be spoken bluntly, and Adams Oshiomhole just did that. His rebuke of the Senate under Godswill Akpabio’s leadership was not only timely but necessary. It captured a sentiment long murmured in the corridors of power and loudly echoed on the streets — that Nigeria’s legislature, particularly the upper chamber, has become a submissive extension of the executive arm of government.

By calling out the speed and superficiality with which bills are being passed, Oshiomhole pierced through the pretense of legislative independence that the current Senate leadership often parades. His warning about the chamber “rubber-stamping” every proposal from the Presidency is not an exaggeration. It’s a reflection of what Nigerians have been seeing: a Senate that rarely questions, never delays, and hardly rejects.

When laws — the very foundation of governance — are treated like routine paperwork, the legislature loses its soul. Oshiomhole’s outrage that four different bills were tabled, debated, and passed in minutes was both rational and patriotic. His insistence that lawmakers cannot meaningfully contribute when complex documents are circulated and adopted on the same day was a reminder that scrutiny, not speed, defines good lawmaking.

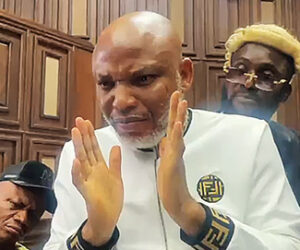

In a functioning democracy, parliament is the conscience of the nation — a check, not a cheerleader. Yet under Akpabio’s Senate, cooperation with the executive has degenerated into subservience. The chamber that should question presidential requests for loans, appointments, and agencies has instead become a conveyor belt, approving everything with applause and prayer.

It is ironic that Oshiomhole, himself a member of the ruling party, is now voicing what the opposition and civil society have long accused this Senate of being — an institution that has traded oversight for convenience. But that irony only makes his words more powerful. Coming from within, his criticism cannot be dismissed as partisan noise; it is a cry for legislative redemption.

Deputy Senate President Barau Jibrin’s admission that Oshiomhole was “right” underscores just how deep the problem runs. When internal voices begin to echo public frustration, the institution should listen. Nigerians are not fooled by the façade of “harmonious executive-legislative relations.” They see what’s happening — a Senate that rubber-stamps budgets, defends questionable policies, and shields the powerful from accountability.

Oshiomhole’s statement that if this continues, “we don’t need a bicameral legislature,” was a brutal but valid point. Why maintain two chambers if one merely imitates the other and both exist only to please the Presidency? Why pay billions in salaries and allowances to senators who pass bills they barely read?

For too long, the Nigerian Senate has confused loyalty to the ruling party with loyalty to the nation. It has forgotten that its allegiance should be to the Constitution, not to the President. A parliament that cannot say no is not a parliament; it’s a department of the executive.

To understand why Oshiomhole’s statement hits so hard, one must go back to the very foundation of democratic governance — the principle of the separation of powers, as famously articulated by the French political philosopher, Baron de Montesquieu, in his 1748 classic “The Spirit of the Laws.” Montesquieu argued that liberty and justice can only exist in a state where the legislative, executive, and judicial powers are distinct and independent.

According to him, “When the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person, or in the same body of magistrates, there can be no liberty… Again, there is no liberty if the judicial power be not separated from the legislative and executive.” Montesquieu’s point was simple but profound: power, if unchecked, inevitably becomes tyrannical. The only safeguard against tyranny is to divide power among institutions that can restrain one another.

The legislature, in this framework, is meant to make laws; the executive to enforce them; and the judiciary to interpret them. None should usurp or submit to the other. Montesquieu’s doctrine was not just a theoretical abstraction — it became the cornerstone of modern democratic constitutions, including Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution (as amended), which clearly separates powers among the three arms of government.

Yet, the reality in Nigeria has often made a mockery of this noble principle. Instead of functioning as an independent lawmaking body, the Senate has too often acted as a political extension of the Presidency. Whenever the executive sneezes, the legislature catches a cold. And whenever the President demands urgency, the Senate responds with obedience, not oversight.

This is the condition Oshiomhole lamented — a legislature that has surrendered its power of debate, its duty of inquiry, and its moral obligation to act in the interest of the people. By fast-tracking bills without proper scrutiny, the Senate is not only undermining its constitutional duty but also violating the spirit of Montesquieu’s separation of powers.

The danger of such complacency cannot be overstated. When lawmakers stop questioning, the executive becomes unaccountable. When senators rush to approve every proposal without examination, corruption finds shelter, incompetence escapes penalty, and democracy loses its meaning. The result is what political theorists call executive dominance — a system where the President effectively governs without institutional restraint, even though democratic forms still exist.

Nigeria’s history offers painful lessons about this. During periods of military rule, there was no legislature to act as a check. The Head of State ruled by decree, and the concentration of power led to abuse, repression, and economic collapse. The framers of Nigeria’s current democracy deliberately designed a system that would prevent such concentration. But what happens when the legislature willingly abdicates its powers? The result is a civilian version of authoritarianism — where power appears distributed but is, in practice, centralized.

Oshiomhole’s concern about the “speed” of lawmaking is not a trivial procedural complaint. It is a deeper philosophical one. Lawmaking is not about efficiency; it is about deliberation. Every bill, no matter how technical, affects lives and institutions. Passing laws in haste, without debate, is legislative recklessness disguised as productivity. It may please the Presidency, but it betrays the people.

The irony is that Oshiomhole is not an outsider to the system. As a former governor, party leader, and now senator, he understands how power is wielded in Nigeria. That he chose to call out his own colleagues — and by extension, his own party’s leadership — makes his intervention even more significant. It signals a moment of rare honesty in a political culture dominated by sycophancy.

What Montesquieu feared centuries ago is exactly what Nigeria risks today: a collapse of institutional independence. If the legislative arm continues to behave like an annex of the executive, then the delicate balance that sustains democracy will crumble. The Senate will cease to be the people’s voice and become, as Oshiomhole warned, a “rubber stamp.”

Deputy Senate President Jibrin’s response, admitting that Oshiomhole was right, offers a glimmer of hope — but words must be matched by reform. The Senate should adopt procedures that guarantee adequate time for bill review, encourage dissenting opinions, and resist executive pressure. Legislative debate is not a nuisance to governance; it is its lifeblood.

Oshiomhole has, whether consciously or not, rekindled the Montesquieuan question in Nigeria: Who checks the powerful? His warning should awaken lawmakers to their sacred duty — to act not as servants of the executive but as custodians of public trust.

If the Senate takes this moment seriously, it can begin to restore faith in democracy. But if it continues to serve as an obedient branch of the Presidency, it will hasten the erosion of the very freedoms the doctrine of separation of powers was designed to protect.

Oshiomhole hit the nail squarely on its head. The tragedy would be if his colleagues pretend not to hear the sound.

(Word count: 1,172)