The 2025 Anambra governorship election, though largely peaceful and well-conducted, was once again blighted by widespread incidents of vote buying, revealing how the corrosive influence of money politics continues to define Nigeria’s elections.

Despite the peaceful atmosphere that characterised the election, multiple cases of vote buying and voter inducement were observed at several polling units, a recurring electoral malpractice that undermines the credibility of Nigeria’s democracy.

Governor Charles Soludo of the All Progressives Grand Alliance (APGA) was re-elected after sweeping the poll in all the 21 local government areas (LGAs), polling 422,664 votes. His closest challenger, Nicholas Ukachukwu of the All Progressives Congress (APC), scored 99,445 votes.

The Young Progressives Party (YPP) candidate, Paul Chukwuma, followed with 37,753 votes, while the Labour Party (LP) flagbearer, George Moghalu, garnered 10,576 votes.

Out of the 2,788,864 registered voters, only 598,229 were accredited, representing turnout of 21.4 per cent. Although this marks an improvement on the 10.3 per cent recorded in 2021, the low participation rate reflects deepening public distrust in the electoral system, largely driven by the pervasive culture of vote trading.

Cash-for-vote: Old tactic, new methods

At Polling Units 017 and 018 in Ward 2, Onitsha South LGA, PREMIUM TIMES observed a more discreet form of vote buying. Voters were asked to write down their bank details in a small notebook being passed around. On inspection, the notebook contained full names, phone numbers, and account numbers of voters.

These observations, made directly by this newspaper’s reporters, show how the practice of inducement has evolved from open exchanges of cash to quieter, subtler negotiations, designed to evade detection by security agents and election observers.

Similarly, in Onitsha North Ward 4, Polling Unit 008, a man believed to be a party agent or a political thug was seen going around and quietly asking voters whether they would vote for his party “so they can be sorted out.”

Elsewhere in Polling Unit 001, voters openly complained that the cash allegedly shared was little. One woman lamented that another unit was giving out N10,000 per voter. An official was overheard telling her, “Nobody begged you to vote,” implying that she could leave if dissatisfied.

At another polling unit, in Onitsha North, several voters expressed disappointment after promises of cash rewards were not fulfilled. Some women who had already voted refused to leave, saying they were still waiting for “the money that was promised.” One woman specifically stated, “APGA people have used my brain.”

A persistent rot in Nigeria’s elections

Vote buying is not new in Anambra or Nigeria at large. It has become a deeply entrenched feature of Nigerian elections, evolving with each electoral cycle despite repeated condemnation by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and civil society organisations.

Over the years in past elections, from presidential to local government polls, political parties have evolved from open cash sharing to distribution of food items, or the promise of post-election rewards to influence voter choices. The 2025 Anambra governorship election followed this familiar pattern, with subtle inducement replacing open bribery in many areas.

It is fair to say that the practice persists because of weak enforcement of electoral laws, widespread poverty, unemployment and decades of disillusionment with governance. Many voters, particularly in rural and low-income urban communities, see election days as a rare opportunity to “collect something tangible” from politicians who vanish after winning.

Vote buying not only compromises the sanctity of the ballot but also erodes public confidence in the process.

This sense of hopelessness has gradually turned elections into cash auctions, where politicians outspend each other to “buy” legitimacy. As a result, credible candidates who refuse to share money are often sidelined, while those with deep pockets or access to public funds gain an unfair advantage.

The implications are far-reaching. When votes are traded for money or material incentives, the people lose their power of choice, and elected leaders feel no obligation to deliver good governance. They owe allegiance not to the people but to the funds that secured their victory.

A citizen who sells a vote loses the moral ground to demand accountability from leaders. Likewise, a politician who purchases votes sees governance as an investment to be recouped, not as a public trust to be protected.

In Anambra, voter turnout, though improved, remains low at just over 21 per cent, showing that millions of eligible citizens stayed away from the polls, partly out of frustration that elections have become commercial transactions. For many, the feeling is that votes no longer count unless backed by money.

Peaceful yet morally compromised

While PREMIUM TIMES correspondents observed that polling was largely peaceful and BVAS machines functioned effectively in most locations, the pervasiveness of inducement painted a grim picture of democracy on sale.

INEC has repeatedly warned that vote buying is a criminal offence under the Electoral Act, yet enforcement remains weak. Security agents at polling stations often look away or intervene only when disputes arise among party agents over sharing arrangements.

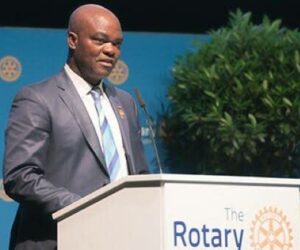

Mr Soludo’s sweeping victory makes him only the second candidate in Anambra’s history, after Willie Obiano in 2017, to win across all LGAs. His historic victory across all 21 LGAs affirms APGA’s continued grip on the state.

But his re-election also took place amid a system where financial inducement overshadowed genuine political conviction. These recurring reports of inducement cast a shadow over the achievement, suggesting that the success of Nigeria’s elections can no longer be judged solely by the absence of violence or the efficiency of technology, but by whether the process is free, fair, and truly independent of financial manipulation.

READ ALSO: Anambra 2025: INEC issues certificates of return to Soludo, deputy

Implications

The 2025 election has once again exposed how vote buying sustains political inequality, discourages voter participation, and corrodes democratic institutions. When citizens are compelled or enticed to sell their votes, governance becomes transactional and accountability, elusive.

Until the culture of electoral monetisation is decisively tackled through stronger law enforcement, civic education, and deterrent penalties, future elections in Nigeria may continue to be decided not by the power of persuasion but by the power of the purse.