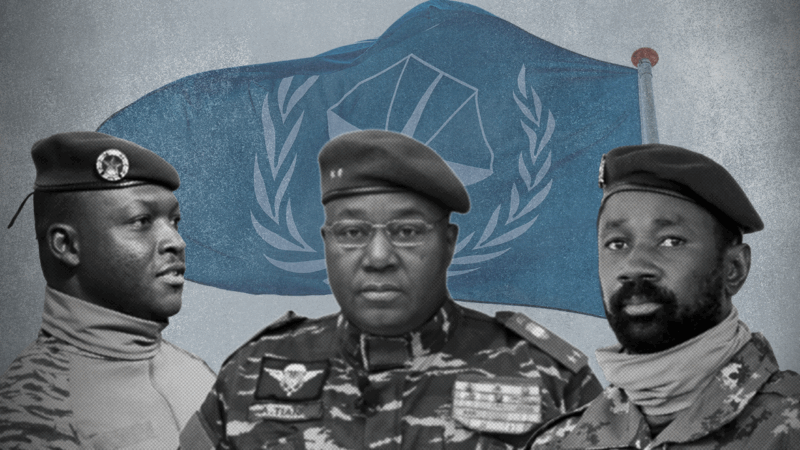

On 22 September, the Alliance of Sahel States (AES), comprising Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, declared it was leaving the International Criminal Court (ICC). This comes seven months after their official withdrawal from the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and ECOWAS Court of Justice.

Speaking at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, Mali’s Prime Minister Abdoulaye Maïga reaffirmed the AES’s commitment to a multilateral system (which would include the ICC) – provided all countries were part of it. He spoke on behalf of the AES and his country. The prime ministers of Burkina Faso and Niger echoed these sentiments. None of them referred to the ICC in their speeches.

The joint communiqué on their ICC exit was issued by Malian President Assimi Goïta in his capacity as AES President. It states that instead of relying on the international system, the three countries would opt for local and endogenous mechanisms to ‘consolidate peace and justice’ and fight impunity. Their primary reason for leaving the court was an accusation of ‘selective’ justice.

This is not the first time the ICC has faced this complaint. The court endured backlash from African countries and the African Union (AU) between 2009 and 2015 for having only African situations on its roll.

In 2022, Amnesty International warned that double standards – or the perception thereof – threatened the court’s future. At the time, the ICC appeared to have weathered the storm of a possible mass withdrawal by African countries.

It is too early to tell if the AES’s exit could reignite desires from the other 30 African ICC member states to follow suit. But that seems unlikely, considering African countries’ recent condemnation of United States (US) sanctions on the ICC.

African states played a critical role in developing the ICC’s Rome Statute and establishing the court. In the years leading up to Rome, countries on the continent collectively articulated clear principles on the form and function of an independent global court with criminal jurisdiction. When the Rome Statute was adopted in 1998, a third of the 120 states that voted in favour were African – the largest single bloc.

Much has changed in the 27 years since. Today, the ICC has 125 member states (33 from Africa, with four African countries joining in the past 15 years). Burundi and the Philippines left the court in 2017 and 2019, respectively. In May 2025, Hungary’s Parliament initiated a withdrawal process, but hasn’t followed through. Kenya, South Africa and The Gambia have expressed intent to withdraw, but either reversed their decisions or never proceeded.

The road to universal ratification hasn’t been smooth for the ICC, and with the court under increasing strain, the AES’s exit certainly undermines this effort.

As the single largest bloc, African ICC member states have been vocal on how to improve the court’s operations and advance international justice. This has led to reforms, including investigating situations beyond Africa, such as in Palestine, Ukraine, Georgia, Bangladesh/Myanmar and the Philippines.

Still, most ICC investigations and cases are in Africa, mainly due to self-referrals by affected countries. Ironically, in 2012, Mali became the fifth African country to refer a situation within its borders to the ICC.

Mali’s referral was the first to be backed by other states. The seven countries were members of the ECOWAS Contact Group on Mali (Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Liberia, Niger, Nigeria and Togo). If the AES states follow through on their withdrawal, the ICC can still work on its active cases in the country, but without the Malian authorities’ full cooperation, this will be challenging.

The sharp change of tack for the three Sahelian countries has been bubbling under since the coups that led to their current junta-led governments. Burkina Faso’s leader, Ibrahim Traoré, hinted at the breakaway almost immediately after taking power in 2022. He has gained popularity through a ‘Pan-Africanist’ message rejecting ‘Western imperialism’ and global institutions like the International Monetary Fund and ICC.

The AES communiqué reiterates the view that international institutions are tools of Western imperialism that apply double standards. Ironically, the US also accuses the ICC of double standards for opposite reasons, seeing the court as a tool to undermine US and Israeli interests.

In June this year, the AES announced it would establish a Sahel Criminal and Human Rights Court, which some analysts opined was an initial step toward ICC withdrawal. The AES says its proposed court will be grounded in local realities and immune from ‘the negative influence of imperialist powers on the organisation and functioning of certain regional and international jurisdictional bodies.’

Yet human rights groups have raised concerns that, without independent accountability mechanisms, the AES’s withdrawal from the ICC widens the impunity gap. The exit limits victims’ avenues for justice, especially in Burkina Faso and Mali, where war crimes and crimes against humanity have allegedly been committed over the past decade.

The contrast between the three states’ aspirations for global accountability in 1998 and their recent rejection of the ICC could not be starker. The three were for decades at the forefront of advancing international justice as a fairer, global platform for accountability. They were among the first countries to sign and ratify the Rome Statute.

Although their exit was announced as ‘immediate’, the Rome Statute provides for 12 months before the decision takes effect. This notice period has seen countries like South Africa reversing their withdrawal. However, the AES is unlikely to change its stance, considering the trio’s follow-through on leaving ECOWAS.

Their decision is a blow for the ICC in particular, and the international justice system in general. The AES is entitled to assert its sovereignty in this matter, but what are the implications for accountability? And does sovereignty without responsibility to citizens not risk degenerating into authoritarianism?

The ICC receives its fair share of criticism, some of which is warranted. However, it was never created to replace national and, in some cases, regional jurisdictions, but rather to complement them. Having multiple spaces for accountability – whether through truth-seeking, transitional justice, criminal justice, rehabilitation or reparations – remains essential.

Whether local, endogenous or transregional, mechanisms must enshrine three key principles underpinning international justice. First, no one is above the law. Second, complementary jurisdictions can provide victims with options. Third, victims’ rights to participate and seek reparations must be assured.

READ ALSO: Lassa Fever: Nigeria records 166 deaths as outbreak spreads across 21 states – NCDC

Unless these principles are factored into any new mechanisms, withdrawal from the ICC risks undermining the foundation of international justice.

Ottilia Anna Maunganidze, Head, Special Projects, Institute for Security Studies (ISS)

(This article was first published by ISS Today, a Premium Times syndication partner. We have their permission to republish).