Enugu is not just promising a better future; it is actively working towards it. With a young, dynamic population and a pressing issue of unemployment, the state is not clinging to traditional education models that merely issue certificates. Under the visionary leadership of Governor Peter Ndubuisi Mbah, and with the Science, Technical, and Vocational Schools Management Board (STVSMB) leading the charge, Enugu is charting a new course. It is transforming Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) from a last resort to a first-choice pathway. The slogan is ‘Tomorrow Is Here,’ but the reality is that the future is being meticulously designed, scheduled, and imparted.

The first task is cultural. For too long, TVET has suffered a branding problem: respected in private, overlooked in public. Repositioning it as a prestigious route to dignity and prosperity means telling new stories—and backing them with new systems. It means seeing a young woman with a welding badge as a leader, not an outlier; a rural boy with a mechatronics credential as a builder of local industry, not a plan B. It means integrating TVET into SS1–SS3 timetables so it sits beside mathematics and literature, not behind them. It means dual certification—WAEC/NABTEB plus a vocational skill badge—so learning produces both recognition and readiness.

But it needs infrastructure too. The Government Technical College, GTC, Enugu, inherited by Governor Peter Mbah was so dilapidated and an eyesore. First, he shipped the students to others schools, insisting that no Enugu child should study in such environment. In July 2024, he descended on the decrepit GTC with bulldozers so that the old, disgraceful relic could give way for something ultramodern.

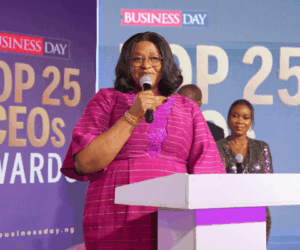

On June 9, 2025, less than a year later, the First Lady of Nigeria, Senator Oluremi Tinubu, commissioned GTC Enugu as the pilot launchpad for TVET in the state with seven more coming up in the remaining seven Federal Constituencies of Enugu State. The choice of GTC for the pilot is both symbolic and strategic: an institution with a history and a location with reach; a neely built ultramodern infrastructure blended learning, including multiple blocks of exquisite hostel with the capacity to take the expected1,200 students. This pilot becomes a statewide standard.

Yet the heart of any transformation beats in the classroom—and in the workshop adjacent to it. Enugu’s curriculum architecture is competency-based and aligned with the National Skills Qualifications Framework (NSQF). Learners won’t just cram; they will demonstrate their understanding. Stackable badges allow progression from foundational competencies to higher certifications, and the assessment is as much about what a student can build as what they can recall. Career guidance and mentorship are not add-ons; they are baked into the timetable. Apprenticeships and industry exposure are not favours; they are formal pathways. The state is making a simple promise to its young people: you will learn, you will earn, and you will be equipped to lead.

This requires a new kind of instructor pipeline—one that combines pedagogy with practical experience. STVSMB’s sourcing strategy is intentionally plural. Tertiary institutions like the Enugu State College of Education (Technical) (ESCET) will do what they do best: pedagogy, trade-specific teaching, and teacher training. IMT Enugu offers engineering, ICT, and business modules. The Colleges of Nursing, Agriculture, and Health Technology extend the frontier into health, biotechnology, and agribusiness. UNN supports curriculum design, mentorship, and research.

Industry will not sit in the spectator stand. Through the “Adopt-a-Trade” programme, artisans, technicians, and entrepreneurs step into classrooms as guest instructors. Corporate partners, such as Innoson Kiara, Haier Thermocool, and the Dewdrop Institute of Hospitality and Tourism, provide trainers and co-design modules. Retired professionals return as master craftsmen and mentors. Standards hold it all together: NBTE’s role in training and certification ensures that excellence is defined nationally, even as delivery is localised.

Two institutional innovations make this pipeline durable. First, the Enugu Centre for Experiential Learning and Innovation (CELI), located at ESCET and inaugurated by Governor Mbah in August 2024, serves as a hub for training and retraining educators across Smart Green Schools being built by Mbah Administration in 260 wards for as a remarkable paradigm shift from rote or memoralisation learning to experiential learning in a 21st Century environment. CELI is where teachers learn to teach the Fourth Industrial Revolution: inquiry-based learning, project studios, digital tools, and maker-space mindsets.

Second, the flagship ESCET–STVSMB Teacher Training Partnership Program, launched on August 11, 2025, and led by Dr. Amaka Ngene, Chairman of STVSMB, sets an ambitious target: to train 1,000 educators in 21st-century pedagogy for science, technical, and vocational education. Modules cover competency-based delivery, blended learning, inclusive and gender-sensitive pedagogy, entrepreneurship integration, and the gritty craft of classroom management and learner engagement. This is not a one-off boot camp; it is a culture. Quarterly workshops keep content current; peer networks and innovation labs keep practices sharp; certification upgrades and refresher courses keep credentials current; KPI dashboards keep everyone accountable.

Those dashboards matter. Transformation without measurement is theatre. Enugu’s outcomes are explicit: 100% of instructors are certified for NSQF-aligned delivery; at least 80% retention across GTCs; annual participation in professional development is at or above 90%; instructor satisfaction and performance are tracked and acted upon. And the learner-side indicators—badge completion, apprenticeship uptake, job placement, enterprise starts—will be defined, collected, and published as the pilot matures. If the promise is that TVET can be a lever for inclusive prosperity, the proof must be that graduates are entering jobs, building micro-enterprises, or progressing into further study without dead-ends.

Digital systems are not just a support, but a crucial part of the initiative, stitching the whole ecosystem together. A learner information system will track progress from SS1 through certification; a placement and apprenticeship portal will match talent to firms in real time; the professional development dashboard will help school leaders coach rather than guess. None of this ignores the human realities of access. Inclusion is a design principle: gender-responsive pedagogy, role-model visibility, and targeted supports for learners with vulnerabilities ensure that TVET does not reproduce old exclusions under a new name. In practice, this means offering scholarships, ensuring safe learning environments, providing flexible scheduling for caregiving students, and implementing community-anchored projects that showcase skills and their value close to home.

Industry partnership is the driving force behind this transformation. When firms actively participate in co-designing curricula, hosting apprentices, donating equipment, and hiring graduates, a trust loop is formed. Students see a clear path to employment; employers see a pipeline of skilled workers; and schools see the relevance of their education being rewarded. Entrepreneurship is also a key aspect, with incubations embedded in TVET Colleges, access to start-up kits and micro-finance, and post-graduation mentoring converting skills into viable businesses. Local economies are not just interested in what is known, but also in what is made, repaired, installed, and grown. TVET is speaking the language of livelihoods.

The timeframe of 2025–2031 keeps everyone focused. The pilot year establishes credibility; the replication phase expands to seven additional TVET Colleges; consolidation standardises NSQF alignment, professionalises the instructor corps, and deepens digital and data capabilities. Throughout, the Governor’s Office and Ministry of Education provide policy cover, funding alignment, and public advocacy; the First Lady’s commissioning lends national visibility; communities and alumni networks widen the circle of support. The North Star remains a bold social goal: to contribute meaningfully to achieving a zero-percent poverty headcount through education-driven empowerment. Lofty? Yes. But poverty is not persuaded by modesty.

There is, of course, risk. Instructor retention depends on meaningful career pathways and fair compensation. Industry engagement must outlast photo-ops. Data systems must protect privacy while enabling insight. And the social rebranding of TVET will take as much storytelling as infrastructure. Yet the architecture is sound because it is coherent: curriculum, capacity, partnerships, data, and dignity reinforce one another.

If Enugu succeeds, it will not merely produce skilled graduates; it will normalise a new social contract between school and society. Young people will not be told to wait their turn; they will be taught to make it. Parents will not measure success solely by university admission; they will also celebrate mastery and financial gain. Communities will not fear brain drain; they will feel brain circulation as skills root and multiply locally. By 2031, the phrase “TVET capital of West Africa” will read less like a boast and more like a description.

And so, the refrain becomes a roadmap: We create with our hands. We rise with our skills. We lead with our purpose. Tomorrow is here—Enugu is ready.

Dr Ukachukwu, a public affairs analyst, writes from Lagos