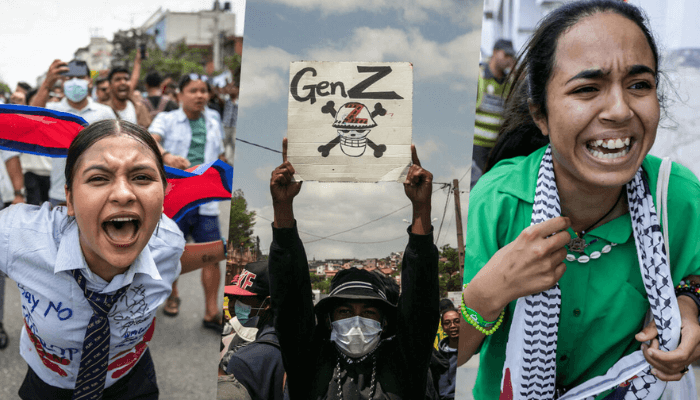

When I first saw images of young protesters flooding city squares in Nepal, Madagascar and Morocco with slogans like “corruption is sus, stop ghosting democracy” boldly written across placards, I half-smiled, thinking: that slogan could have surfaced in a Lagos teenager’s group chat. It is not a mere coincidence. The phenomenon of youth-led protest movements around the world, driven by the generation often labelled ‘Gen Z’ (roughly born in the late 1990s into the 2000s), has implications that localise powerfully to Nigeria.

In places as disparate as Indonesia, the Philippines, Kenya and Peru, young people connected through shared social media platforms and frustration with governance have emerged as potent forces. In Nepal, a sudden social media ban triggered mass mobilisation; in Madagascar, a breakdown in water and electricity services ignited revolt. Though the immediate catalysts differ, the underlying story is familiar: young societies, frustrated by systemic failures, harness digital networks for collective action.

“Nigeria must therefore watch out for trigger events: a large fuel-price shock, Internet shutdown, sudden spike in food inflation, election manipulation, consistent insecurity, police harassment, and unabated suffering. Any could spark mobilisation.”

It is easy to think back to the wave of uprisings during the Arab Spring in the early 2010s when young people in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya and beyond upended established regimes. Many of those hopes dissolved without meaningful improvement in youth lives. Today, the Gen Z wave feels like a sequel, faster, more global, and more digitally native, and Nigeria could well sit in its path.

In Nepal and Madagascar, median ages (28 and 21, respectively) helped frame movements built on a young population, high unemployment, weak governance and ubiquitous social media. The same structural realities are visible in Nigeria. According to the latest survey by Afrobarometer, Nigeria’s median age is around 18.1 years, and 58 per cent of the population is under age 30.

Young Nigerians are reporting sharply negative impressions of their economy and personal prospects. One poll shows only 6 per cent of youth think their government is doing “fairly well” on jobs, and just 2 per cent believe inflation control is handled competently.

And the unemployment story, even with statistical cautions, is troubling. Official figures report 6.5 per cent unemployment among 15-24-year-olds in Q2’2024, but many analysts argue the true level of youth disengagement is far higher.

Digital culture has helped knit these young citizens into a global tribe. Across continents, platforms like TikTok, Discord, Instagram, WhatsApp, etc., have become shared protest grounds. In Nepal, demonstrators cited movements in Indonesia; in Madagascar, even the young journalists noted inspiration from Nepal. The chain links from Lagos to Kathmandu.

What happens when the same ingredients come together in Nigeria? A massive youth population, rising cost of living, underemployment and a sense of being left behind. The setting is prime for unrest. In Nigeria, more than 80 million people live in poverty; youth unemployment (or lack of meaningful employment) is frequently cited as a root of insecurity and unrest.

Gen Z in Nigeria is not merely spectators. They are electronically connected, socially aware, and politically disappointed. According to Afrobarometer, 23 percent of youth aged 18-35 say they are unemployed and actively seeking work, while many others say they are unwilling to remain passive.

Could these young Nigerians mimic the sorts of uprisings seen elsewhere? It is possible. Many of the characteristics align: a young populace, digital connectivity, a sense of exclusion or betrayal, and visible failures of infrastructure and governance. And as we have seen elsewhere, these protests can escalate surprisingly quickly.

Read also: Madagascar plunges into chaos as Gen Z uprising drives president into hiding

Yet here lies the core paradox – Gen Z demonstrators can bring about change, but they may not control what happens next. In Madagascar, following the protests that chased out the president, a former opposition politician assumed leadership of the legislature, prompting dismay among the youth-led movement, who feared their energy had been co-opted. In Nepal, one young activist noted, “What if everything goes back to the same way, even after we lost our blood and fallen comrades?”

The crux of the matter is, even securing regime change does not guarantee structural transformation, especially when the issues are deep and systemic. As researcher Abigail Branford puts it, “Youth unemployment, weak institutions, patronage and weak economies aren’t easily reversed just by raising placards.”

In Nigeria, the stakes are high. Any protest may lead to demands, resignations or policy pledges, but unless deeper economic, governance and institutional deficits are addressed, the young activists may find themselves disappointed. The current administration’s focus on youth empowerment and skills (for example, through vocational training) is welcome, but critics argue it is insufficient against the sheer scale of the challenge.

Nigeria must therefore watch out for trigger events: a large fuel-price shock, Internet shutdown, sudden spike in food inflation, election manipulation, consistent insecurity, police harassment, and unabated suffering. Any could spark mobilisation.

Digital mobilisation: a flyer, a viral TikTok video from a Northern town, and a WhatsApp chain calling for “Walk for Jobs” in Lagos. Unexpected alliances: Young students, informal‐sector workers, and tech-savvy creatives unified by hashtags and common experience.

Post-protest risk: If the power vacuum is filled by the old-guard elite with no meaningful reform agenda, the next generation may feel disillusioned, and the protest energy may dissipate or turn destructive.

For Nigeria, this is not a distant scenario. The youth have shown they are ready. The question is: Will the political and economic system react in time? The old models of patronage politics, short-term programmes and marginal vocational schemes are insufficient. If young Nigerians feel their values, their vocabulary, and their demands for dignity go unheeded, they may write a new chapter.

Much like the Arab Spring before it, the Gen Z uprisings are both a promise and a warning: a promise because young people are no longer powerless and a warning because adapting to their voice requires structural change, not just rhetoric.

In Nigeria’s case, what may look like another protest wave could evolve into a critical juncture. The youth are connected. They are frustrated. They are watching, and they have power. The contagion is not destiny, but ignoring it just might be.