2

LAGOS – In a world drowning in discarded cables, nails and rebar, Chubby Daniels sees something most people threw away long ago: potential.

Originally trained in architecture and sustainability, he traded blueprints for welding masks, structural wires for narrative threads, and turned his civil-engineering instincts into a sculptural voice.

Where others only see junk, Daniels seizes every bent nail, every frayed wire, every forgotten piece of metal, and invites them back into the story of life.

Chubby Daniels sculptures aren’t merely metal forms, they are stories rewritten—of resilience, regeneration, identity, and the alchemy of what was deemed worthless into something incandescent.

His technique transformation is awesome.

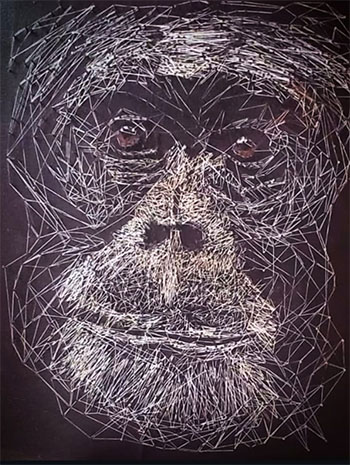

Daniels has developed a method that goes far beyond conventional metal-sculpture practice.

His signature approach might be called structural weaving: taking used nails, cables, sheet scraps, wires and rebar, then weaving, welding, bending and weaving again until the material transforms into something— alive.

For Daniels the stiff skeleton of rebar becomes the “bone”, the armature, the hidden architecture of the beast.

He transforms electrical wires to become “thread” for detailing—manes, muscles, sinew—allowing light to weave through the form, giving the heavy metal a surprising weightlessness.

Nails, often welded by their heads, create tactile textures: elephant hides, rhino skins, lion manes, each nail a micro-history—rusted, bent, marked.

Daniels acknowledges: “I am not forcing it to be something new; I am collaborating with it to reveal a new form.”

His method produces sculpture that breathes. The negative space is as important as the positive surface: light, shadow, tilt of head— all emphasizes motion, tension, emotion.

In his signature works and themes such as Skyward Kiss (the giraffe) and Lion King (the lion), Daniels brings both grandeur and detail together. The giraffe’s impossibly long neck is not a hollow tube but a woven column of tension-wires; the lion’s mane is a cascade of individually placed copper wires that shimmer; every shift of the viewer changes the light and the perception of movement.

Beyond the animal forms, the works speak of identity, resilience, transformation.

Coming from Nigeria and now practising in the UK, Daniels bridges materials, cultures and stories. He poses the question: if we abandon our waste, what are we also abandoning? And if we reclaim it, what can we become?

For Daniels, it is not art for art’s sake. He uses his work as environmental advocacy, a persistent challenge to the throw-away culture: every twist of wire, every strike of a welder becomes an argument for sustainability, reuse, regeneration.

As one Nigerian newspaper put it, “turning discarded materials into masterpieces … proving that art can be both beautiful and environmentally friendly.” – (Independent Newspaper Nigeria)

His community-facing initiative, Trash to Art (UK & Nigeria) sees him running workshops, transforming local waste into wonder, inviting communities—especially young people—to join the dialogue on consumption, creation and identity. Daniels remains a gift to our world.