At the start of Governor Ahmed Aliyu administration, it felt like Sokoto state was hosting a permanent concert of criticism. Foot soldiers of the former governor, now Senator Aminu Waziri Tambuwal, took it as their calling to antagonise the new technocrat at every turn. They beat their ganga loud and strung their garayas long. Fast forward to nearly three years into Aliyu’s tenure, and the songs have simply stopped. The opposition that once made itself heard on every street corner has all but vanished. The question on everyone’s lips is: did the sponsors of that noise run out of funds, or did the hecklers simply run out of arguments?

Truth is, neither mystical river ran dry overnight. What happened is more straightforward and, to me, more interesting: performance trumped propaganda. While opposing noises were permeating the air, Gov. Aliyu kept his head down and got to work. While others were busy composing rebuttals and orchestrating campaigns of calumny, he focused on delivering things people can see and feel. So, in place of politics that thrives on volume rather than value, Aliyu delivered visible results in every sector of governance, and that has made all the difference.

Take security, the issue that has a way of cutting across party loyalties. Aliyu did not offer a litany of promises; he engineered practical responses. His administration distributed a large fleet of patrol vehicles to security agencies across the state and set up a supplementary Community Guard Corps to boost local security efforts. Those patrol vans and the new community corps have proven to be more than mere symbolic parade props; they are mobile, they move where the trouble is, and they help reclaim spaces that once felt unsafe. That tangible shift in the state’s security posture is one reason the loudest critics have grown quieter.

He also went after structural solutions. The state government moved to support the operational capability of the Nigerian Air Force in Sokoto, a step that has strengthened aerial surveillance and response for the wider region. In tandem with that, the administration initiated construction of a new military facility in Illela, a strategic location along the border that had long been vulnerable. The logic is simple: boots and wheels are good, but the right infrastructure and aerial support multiply their effect. Citizens who once feared nightfall are talking less about blame and more about movement. Market traffic has since blossomed, farmers are back in their fields, and kids are back in their schools.

Aliyu’s security moves have a second dimension: they come with attention to the men and women on the front lines. The state has increased allowances and improved welfare for security personnel posted to volatile areas. That gesture matters. A motivated and cared-for security force is less likely to give ground or give in to fatigue. It also signals seriousness to communities that have been told ‘help is coming’ for years, but often saw little follow-through. The calm in some of these villages is a testament that when people feel safer and security agents feel supported; the political theatrics of opposition lose much of their bite.

Beyond security, infrastructure has been the most visible proof of Aliyu’s intent. The administration has pushed a hefty rehabilitation programme for township and rural roads, projects that immediately change how people live. As we know, where roads are fixed, traders move goods faster, healthcare workers can reach patients, and farmers can take produce to market without losing days on bad tracks. The transformation of secondary roads and the ongoing housing and urban works programmes have a multiplying effect on everyday life; these are the sorts of changes voters notice and recall when the next slogan comes through the loudspeaker.

Energy is another example where the governor has combined promise with follow-through. His government moved decisively to complete and commission a major Independent Power Project which has significantly improved power supply in several local government areas that for years lived in the dark. Again, where small businesses can depend on electricity, livelihoods return and investments become less risky. The quiet hum of a functioning generator can do more to silence critics than a thousand press conferences.

Healthcare and education have not been left out of the equation. The administration approved renovations and upgrades for a number of hospitals and schools across the state, focusing on places that serve large swathes of rural communities. These tangible projects are everywhere. They are day-to-day fixes, clinic wards painted and roof-repaired, classrooms habitable again, essential equipment procured. For people who have watched clinics sit idle for years, these are the kinds of improvements that change faith in government. Recent coverage and releases from the state house have highlighted these projects as part of a broader push to make services reach the grassroots.

And when emergencies happen, Aliyu has been visible and hands-on. The governor’s presence in affected communities, his direct engagement with displaced families, and the rapid delivery of relief items and support have become a pattern. That personal involvement matters. People want leaders who show up in person, not just send statements. When a governor walks through an IDP camp, speaks with a bereaved family, and personally assures follow-up, those images reverberate in ways paid-for narratives cannot drown out. The rescue operations and coordinated responses to kidnappings and attacks, sometimes in partnership with federal forces, reinforced the sense that Sokoto is being governed by someone who will act rather than pontificate.

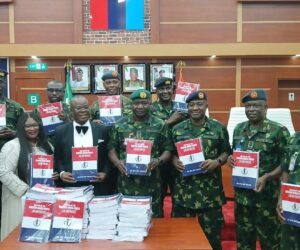

It’s also worth noting that the Aliyu administration has started to attract recognition beyond local talk shows. Awards and commendations have followed. These are acknowledgements that help shift the framing from partisan squabble to administrative competence. When outside observers take note, it constrains the space for mere noise. Praise from peers and national media gives the public a second source to confirm what they already see on the ground.

So what becomes of those who were once paid to heckle? Some will always be there, practicing the trade of loud politics. Others find the business model weak when the market they sell to — the electorate — becomes more interested in clean water, fixed roads, a safer street, a powered clinic. Performance changes incentives. When a government moves from promise to measurable action, the argument that worked before; that everything is a scam, starts to look empty.

I’m not saying the governor’s record is flawless; governance is a continuing set of tasks, and critics should exist where they are constructive. But there is a marked shift in Sokoto: the opposition’s volume has given way to the quiet evidence of improvement in daily life. The disappearance of the earlier, shriller antagonists has more to do with this record of impact than with anything else. People are trading slogans for utility, and that is a healthy sign for democratic accountability.

In the end, politics in Sokoto today feels less like a shouting match and more like a negotiation over what works. Governor Aliyu’s style, steady, hands-on, and focused on delivering outcomes, has altered the conversation. The proselytisers of noise have less purchase when the roads are smoother, patrol vehicles are on the beat, the airspace is better monitored, and schools and clinics are functioning again. That, more than any spin, explains why the opposition has faded: results are hard to shout down.

If politics is judged by the ability to improve daily life, then recent months in Sokoto state suggest a simple verdict. The people can see the difference, and when the difference is visible, the theatrics dissipate. For now, at least, Governor Aliyu’s record of impact is the clearest explanation for the vanishing opposition and for a state that is quietly beginning to breathe a little easier.