Part 7 recap:

In Part 7, Jimmy finally crossed the Mediterranean, but not without tragedy. When the overloaded boat capsized, he swam through the chaos of bodies and saltwater, clinging to life as helicopters circled overhead and rescue boats raced to pull survivors from the sea. He reached Italy alive but uncertain. This was a 17-year-old boy caught once again in a system that didn’t know what to do with him.

Migrant camps replaced cells. Endless interviews replaced chains. He poured out his trauma to judges and therapists, only to be denied asylum. After four years of waiting, Jimmy was still undocumented, still in limbo, and yet still fighting for his future.

Catch up here: Part 7: How a Nigerian teen trafficked through Libya became a celebrity barber in Europe

“Just like that,” he said. “They told me I had to leave.”

But the system allows for two tries.

After the first rejection, Jimmy had one year left in Italy, and one more opportunity to appeal. This time, he would be given a lawyer. Someone to represent him. Someone to fight for him.

But even lawyers can’t bend the truth into proof.

“They asked me for evidence,” Jimmy said. “Pictures, documents, proof that I was tortured. Proof that I drank my own piss in the desert. Proof that I was hung and beaten. But how? There’s no camera in the camps. No files in the ghetto. Who’s documenting trauma when you’re fighting to stay alive?”

There was no footage of the torture. No paperwork from the men who trafficked him. No stamp in his passport that said: “Survived Hell.”

“How do you prove a life lived in the dark?” He had one year left, and no idea what came next.

Surviving in Italy

Jimmy’s request for international protection was denied.

In Italy, you get two chances. After the first rejection, you’re allowed to stay and try again. So Jimmy stayed and waited. What was meant to be a temporary stop turned into nearly four years in the camp system.

He spent those years in limbo, living among other displaced people from across the world: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Bangladesh, and Gambia. Different languages, different scars, the same suspended future.

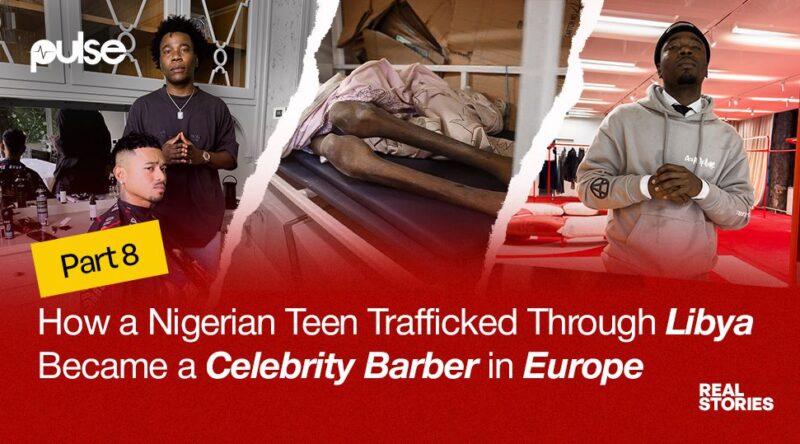

While waiting, Jimmy decided to put his skills to good use. “I started telling people I was a hairstylist,” he said.

It wasn’t exactly true, but it wasn’t false either.

Back in Libya, he had cut hair in prison camps using nothing but blades and combs. Now, in the camps of Italy, he had access to electricity, mirrors, and YouTube.

He started watching tutorials of American barbers explaining fades, tapers, blends, how to shape a hairline. He’d study at night, memorise techniques, then wake up and look for someone in camp willing to let him practice.

“They thought I already knew what I was doing,” he laughed, “but I was just learning. Every cut was practice.”

And it started working. One by one, the other migrants began lining up to get “fresh.” It was one of the few things that made them feel good, feel human again.

Then on his 18th birthday, one of the Italian volunteers, someone who had seen his dedication, who had watched him cut hair day after day, walked up to him with a gift.

A Wahl clipper. His first real tool.

“That clipper changed everything,” Jimmy said. “I wasn’t using blades anymore. I could actually start doing clean fades. That’s when I really felt like I could build something for myself.”

For a while, things felt like they were taking shape. He had found purpose. He had found his craft. But nothing lasts forever in the camp system.

In his fourth year, Jimmy was called for his second trial, the final chance to plead his case.

He went back into that room, told his story again, now with more language, more clarity, more strength. But the answer didn’t change.

They said no. And this time, it wasn’t just a rejection. This time, they handed him an official notice.

He had 60 days to leave Italy.

And when that letter comes, the rules are clear: you’re out of the camp. No support. No shelter, no food. Just the streets.

“I packed up my things, my clipper, my little bag, and left,” Jimmy said. Out into the world with no home, no job, and no plan.

For days, he slept in a train station. Curled up on cold concrete, hiding his bag under his body so it wouldn’t be stolen. His clipper was still with him, but there was nowhere to plug it in.

“It was the lowest I had ever felt,” he said. “After everything, I was back to nothing.”

But Jimmy wasn’t ready to quit. He found another lawyer. Paid what he could. Started the asylum process all over again. That bought him more time in Italy, but under different terms.

He could stay, but he couldn’t work.

Still, he had to eat. So he joined the invisible workforce of Italy: the “black jobs,” where migrants worked off the books. No contracts, no insurance, no safety. If you got hurt, you got hurt. No one was responsible.

One of those jobs took him to an olive farm. They harvested under the sun, cutting, bending, hauling heavy sacks uphill. It was brutal work. And they paid €50 a day. In cash.

But one day, while he was working, the police came for a routine check. They were looking for undocumented workers like him. So naturally, Jimmy ran.

He ducked behind a tree line, heart pounding, eyes scanning the road. If they caught him, he could be deported immediately. The man he worked for found him crouched in the dirt.

“Why are you hiding?” the man asked.

Jimmy told him the truth. He had no papers, and he wasn’t supposed to be there. The man looked at him for a long time. Then he said, “Come with me.”

He brought Jimmy to his office, pulled out some papers, and said, “I’m going to register you. I’ll pay your taxes. That way, you don’t have to run anymore.”

For a month, he kept Jimmy on payroll. Paid him officially, logged his hours, paid his taxes. At the time, Jimmy didn’t know what that meant. He just thought it was kindness. A rare break in the storm.

But later, when his back was against the wall again, that small act of humanity would become the key that unlocked his future.

Don’t miss Part 9 of Jimmy’s story next Friday, only on Pulse.ng