Nigeria’s recent high-profile delegation to Washington, led by National Security Adviser Nuhu Ribadu, was billed as a critical opportunity to recalibrate security and counterterrorism cooperation with the United States. Yet the optics tell a troubling story: a team featuring the NSA, the Inspector-General of Police, the Attorney General, and senior military and intelligence officials meeting with a first-term congressman with no formal role in foreign policy or appropriations committees. The question is simple but urgent: did Nigeria engage strategically or merely play for headlines?

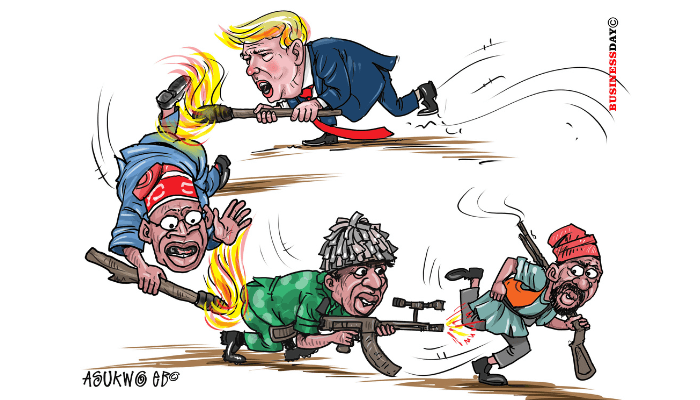

Congressman Riley M. Moore’s press release after the meeting was unambiguous. He framed Nigeria as failing to protect Christians and unable to contain terrorism, echoing President Trump’s well-publicised “no tolerance” rhetoric. Yet Moore is neither a policymaker in the State Department, AFRICOM, or congressional foreign relations committees, nor a decision-maker on U.S. security funding. His influence is political, ideological, and tied to Trump-aligned conservative blocs. If the Nigerian delegation intended to shape U.S. policy substantively, it appears they misread the landscape.

The issue goes deeper than one meeting. Washington is a layered ecosystem: the State Department sets policy, AFRICOM coordinates operational support, Congress controls budgets, and political blocs shape narratives. Effective diplomacy requires engaging all layers strategically, not allowing a single narrative amplifier to dominate. The absence of public reporting on meetings with the State Department, AFRICOM, or the Senate Foreign Relations Committee raises uncomfortable questions about Nigeria’s planning. If Moore was the centrepiece, Abuja’s approach reflects reactive diplomacy rather than calculated influence.

This is more than a misstep in protocol; it is a symptom of Nigeria’s broader foreign policy misalignment. Conservative U.S. actors have amplified reports of Christian persecution and insecurity in the Northeast and Middle Belt for months. Instead of proactively shaping the narrative with verified data, reforms, and intelligence, Nigeria responded defensively. By failing to own the narrative, Abuja ceded the moral high ground, allowing a U.S. lawmaker to frame the discourse unchallenged.

Beyond the optics, Nigeria’s security crisis is far more complex than religious persecution alone. Boko Haram, ISWAP, banditry, and farmer–herder conflicts intersect with systemic governance failures: ineffective arms procurement, weak intelligence coordination, porous borders, and uneven justice enforcement. A strategically aligned delegation would have presented this multidimensional reality, demonstrating how U.S. support could strengthen institutions, rather than simply highlighting the plight of one religious group.

Read also: US barred Nigerian officials from Nicki Minaj’s UN discussion on Christian persecution, Envoy says

Nigeria’s delegation, while impressive on paper, signals either misreading or misprioritisation: either Abuja does not fully understand Washington’s diplomatic hierarchy, or it prioritised visibility over policy outcomes. High-ranking security and intelligence officials rarely meet a congressman unless in the context of a major bilateral negotiation or urgent crisis. The lack of visible engagement with core U.S. foreign policy actors leaves room for scepticism.

What should have happened? A truly strategic mission would have:

Engaged the State Department’s Africa Bureau to shape policy directives;

Consulted AFRICOM leadership on operational counterterrorism cooperation;

Briefed the Senate and House Foreign Relations Committees on controlling security assistance;

Issued a data-driven joint press statement to correct misconceptions; and

Secured concrete agreements for intelligence-sharing and counterterrorism collaboration.

Congressman Moore’s role should have been limited to narrative amplification, not defining the visit. Nigeria needed to control the messaging with evidence, demonstrating both the complexity of its security environment and the reforms it is implementing.

Looking forward, Abuja must recalibrate. Washington is not a monolith; it is a maze of power, influence, and funding streams. Nigeria’s credibility depends on coordinated diplomacy, clarity of purpose, and confidence. High-profile visits alone, absent strategic targeting and evidence-based messaging, risk returning little more than photo opportunities and press releases.

If Nigeria seeks genuine cooperation, it must first show coherence at home: transparent governance, consistent security outcomes, and accountability in intelligence and law enforcement. Until then, even the most senior delegations risk leaving with optics but no leverage.

The takeaway is clear: engaging political amplifiers is not wrong; ceding the narrative to them is. Nigeria’s Washington gamble is only worthwhile if strategy, not desperation, dictates its moves. Otherwise, the country continues to travel far only to arrive at the same precarious place.