The IMF’s upgraded forecasts and plunging inflation suggest the reform gamble is paying off. But euphoria would be premature.

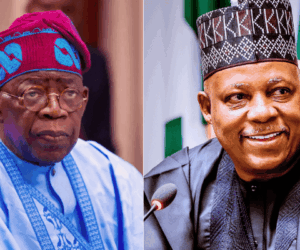

When the International Monetary Fund upgrades a country’s growth forecast not once but twice in three months, markets tend to sit up and take notice. When that country is Nigeria—a perennial underperformer saddled with chronic inflation, oil dependency, and a reputation for false starts—the attention becomes even more acute. The Fund’s October World Economic Outlook projects Nigeria’s economy will expand by 3.9 percent in 2025 and 4.2 percent in 2026, upward revisions of 0.5 and 0.9 percentage points, respectively, from its July estimates. Coupled with September’s dramatic inflation collapse to 18.02 percent—the first sub-20 percent reading in three years—Africa’s largest economy appears to have turned a corner. Yet this is a story less of triumph than of tentative vindication. The numbers confirm what many have privately hoped but few dared to state publicly: the painful reforms undertaken since President Bola Tinubu took office in May 2023—removal of the costly petrol subsidy, unification of the multiple exchange rates, and a hawkish monetary policy stance—are finally bearing fruit. But the light at the end of the tunnel remains distant, and the tunnel itself is still crowded with obstacles.

Read also: Founders, investors tap value creation, collaboration in driving Nigeria’s economic future

The reform premium

The IMF’s upgraded forecast rests on what economists call “supportive domestic factors”. Translation: Nigeria has begun to do things right. The naira, which was trading at over 1,900 to the dollar in the parallel market earlier this year, has appreciated significantly as the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) cleared its foreign exchange backlog and restored transparency to the forex market. External reserves have risen to $42.63 billion as of mid-October, supported by improved oil production, diaspora remittances, and portfolio inflows. Investor confidence, that most fragile of economic sentiments, has strengthened. Perhaps more critically, Nigeria’s limited exposure to the new wave of global tariff wars—particularly the protectionist measures emanating from Washington—has insulated it from the economic headwinds buffeting more trade-dependent economies. While advanced economies are projected to grow at an anaemic 1.5 percent and emerging markets face a slowdown, Nigeria has managed to buck the trend. The IMF’s Denz Igan noted that “reduced uncertainty and Nigeria’s limited exposure to US tariffs” have been key drivers of the upgraded outlook. The Fund also revised its 2024 growth estimate upward to 4.1 percent, reflecting the authorities’ GDP rebasing exercise, which now captures previously underreported sectors such as the digital economy, informal agriculture, and modular refining. This is not statistical sleight of hand; it represents a more honest accounting of what Nigeria’s economy actually produces. The oil sector, once the engine of growth, now accounts for just 4 percent of GDP, down from 8 percent in 2021. The economy is diversifying, slowly but surely.

“The National Bureau of Statistics’ rebasing of the Consumer Price Index, which shifted the base year from 2009 to 2019, accounts for part of the technical decline.”

Inflation’s dramatic surrender

If the IMF upgrade was a vote of confidence, September’s inflation data was a standing ovation. Headline inflation fell to 18.02 percent, down from 20.12 percent in August—a 2.1 percentage point drop in a single month. This marks the sixth consecutive month of decline and represents a stunning 14.68 percentage point reduction from the 32.7 percent recorded in September 2024. Food inflation, the scourge of Nigerian households, plummeted to 16.87 percent from 21.87 percent in August, driven by sharp declines in the prices of maize, garri, beans, millet, potatoes, and other staples. More remarkable still: Nigeria recorded its first month-on-month food deflation in over 13 years, with food prices declining by 1.57 percent in September. This is not merely a statistical quirk. It reflects the onset of the harvest season, improved farm-to-market logistics, and, crucially, the easing of insecurity in key agricultural zones. For a country where households spend up to 70 percent of their income on food, this is nothing short of a lifeline. But context is everything. The National Bureau of Statistics’ rebasing of the Consumer Price Index—which shifted the base year from 2009 to 2019—accounts for part of the technical decline. The IMF, ever the realist, projects average consumer prices will decline from 31.4 per cent in 2024 to 23 percent in 2025 and 22 percent in 2026. End-of-period inflation is forecast at 21 percent in 2025 and 18 percent in 2026. Translation: while the trajectory is positive, the absolute level of prices remains punishingly high.

Read also: Reps move to protect private investments from economic sabotage

The per capita problem

Here is where the enthusiasm must be tempered. A 3.9 percent GDP growth rate may sound impressive on paper, but set against Nigeria’s population growth rate of approximately 2.4 percent per annum, the real gain in per capita income is a paltry 1.5 percent. For a country with a population of 237.58 million—and growing—this is not the stuff of prosperity. It is the mathematics of marginal improvement. Moreover, the economy continues to face the structural challenge of absorbing an estimated 3.5 million new entrants into the labour force annually. Strong GDP growth alone will not solve this problem without targeted reforms to improve the ease of doing business, address the chronic power deficit, and expand access to credit for small and medium-sized enterprises. As Bismarck Rewane, CEO of Financial Derivatives Company, aptly put it, “You cannot grow the economy with what we’ve seen today without a broad power solution.”

Fragile gains, persistent risks

The September inflation data offers tangible relief, but the gains remain fragile. Food inflation is inherently volatile, and the structural issues that have plagued Nigeria’s agricultural sector—insecurity in food-producing regions, inadequate power supply, poor infrastructure—have not been resolved. The recent hike in fuel prices following the removal of subsidies has already begun to ripple through the economy, raising transport and energy costs. The IMF’s projection of 23 percent average inflation for 2025 is a reminder that the battle is far from over. Nigeria’s current account surplus, which stood at 6.8 percent of GDP in 2024, is expected to narrow to 5.7 percent in 2025 and 3.6 percent in 2026 as higher imports offset oil export gains. The CBN, having cut the benchmark interest rate to 27 percent in September for the first time in five years, will need to tread carefully. A premature easing of monetary policy could reignite inflationary pressures, undoing the hard-won gains of the past year.

Read also: Nigeria eyes science as new economic engine

The verdict

Nigeria’s economic story in 2025 is one of cautious optimism. The IMF’s upgraded growth forecast and the dramatic decline in inflation are welcome developments, signalling that the reform agenda is beginning to work. But this is a marathon, not a sprint. To turn these medium-term projections into sustained, inclusive growth, Nigeria must deepen its structural reforms: fixing the power sector, securing agricultural zones, improving infrastructure, and mobilising domestic revenue through effective tax measures. For now, the light at the end of the tunnel is getting brighter. But Nigeria remains very much inside the tunnel. Prudence, not celebration, should be the order of the day. The bitter medicine is working, but the patient is not yet cured.

Dr. Oluyemi Adeosun, Chief Economist, BusinessDay Media