Nigeria’s micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) are competing for relevance in the era of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

The agreement offers access to a $3.4 trillion market spanning 54 countries and 1.4 billion people, but that opportunity must be earned. Only those with efficient supply chains, strong industries, and globally competitive products will truly reap the benefits.

Nigeria’s MSMEs, which account for 96 percent of all businesses and employ 84 percent of the workforce, are at the center of this challenge. The opportunities are immense, but so are the obstacles: weak infrastructure, limited financing, and unpredictable policies continue to drag behind progress. As Ghana and Kenya move swiftly to position themselves, Nigeria faces a defining question. Will its SMEs rise to claim the AfCFTA moment, or be left watching from the sidelines?

Read also: Nearly two-thirds of Nigerian MSMEs owners are 26–45 age group

This is the crossroads where numbers meet strategy, and survival meets scale.

Benchmarking competitiveness: Nigeria vs. peers

To unlock AfCFTA’s $3.4 trillion opportunity, Nigerian SMEs must measure up against regional rivals already positioning themselves as continental leaders. BusinessDay’s SME Competitiveness Scorecard benchmarks performance across five indicators: productivity, logistics, access to finance, digital adoption, and regulatory environment.

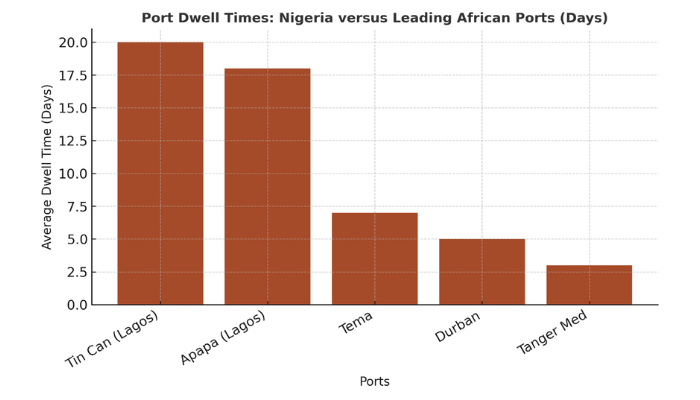

On productivity, Nigerian SMEs lag with output per worker nearly 30 percent below Ghana’s and 40 percent below Kenya’s, reflecting weak infrastructure and inconsistent power supply. Logistics remains a bottleneck. While Ghana’s modernised Tema Port ranks among West Africa’s most efficient, Nigerian exporters face delays averaging 20 days at Apapa, inflating costs.

Finance access tells another story: only six percent of Nigerian SMEs report access to formal credit, compared to 18 percent in Kenya, where fintech lending is reshaping SME capital flows. In terms of digital adoption, Kenya again leads, driven by mobile money and e-commerce penetration. Nigeria shows strong potential, with rising internet usage but uneven broadband coverage. Regulatory hurdles remain steep in Nigeria, with issues such as land titling, taxation, and policy unpredictability hindering the agility of SMEs.

According to the Bashir Adeniyi of the Centre for International Trade and Investment (BACITI), global supply chain disruptions and port inefficiencies pose a threat to Africa’s competitiveness. In Nigeria, where over 80 percent of trade flows through its ports, delays averaging 18 days–20 days continue to undermine export readiness. Strengthening logistics, digitalisation, and trade infrastructure is thus not peripheral—it is central to the success of AfCFTA.

Nigeria’s SMEs—representing 96 percent of businesses and 84 percent of employment—stand at the front line of this transformation. Their performance will determine whether the country becomes a continental trade hub or lags behind regional peers, such as Ghana and Kenya, who are already leveraging the potential of the integration.

The comparative snapshot is clear: while Nigeria has scale and market depth, Ghana leverages logistics efficiency, and Kenya thrives on digital-finance integration.

Barriers & Blind Spots

Nigeria’s SMEs continue to be hindered by structural barriers that impede their competitiveness in the AfCFTA era. Infrastructure and logistics top the list. Congested ports in Lagos, chronic road bottlenecks, and high transport costs often erase the pricing advantage Nigerian exporters should enjoy. Clearing goods through Apapa or Tin Can Island can take up to three weeks—compared to less than a week at Ghana’s Tema Port.

Read also: Kano govt boosts MSMEs, distributes ₦800m to 5,384 youths

In 2023, Lagos ports handled about 1.5 million Twenty-foot Equivalent Units (TEUs), accounting for 70 percent of Nigeria’s container trade. Yet, efficiency remains a major concern. The World Bank’s 2023 Container Port Performance Index ranked Lagos ports 311 out of 370 globally. With average dwell times of 18 days–20 days, compared to just three days –seven days at leading African ports, Nigeria’s trade competitiveness faces a significant logistical drag.

Finance access is another critical blind spot. Less than 5 percent of Nigerian SMEs have access to formal credit, which is significantly lower than that of their regional peers. High interest rates, collateral demands, and weak credit profiling exclude most businesses from capital needed for scaling and regional expansion.

Policy inconsistency further compounds the problem. Frequent regulatory shifts, currency volatility, and opaque tax regimes make long-term planning a gamble, discouraging investment in expansion and innovation.

Finally, skills and technology readiness remain limited. Only about 30 percent of Nigerian SMEs are digitally equipped, compared to nearly 60 percent in Kenya. This gap undermines participation in e-commerce, cross-border platforms, and digital payments—critical enablers of AfCFTA trade.

Unless these blind spots are addressed head-on, Nigeria risks entering AfCFTA with scale but without agility—watching others capture the gains.

Emerging strengths

Despite deep challenges, Nigeria enters AfCFTA with undeniable strengths. Its 220+ million consumer base is the continent’s largest, offering SMEs a domestic springboard before scaling regionally. This sheer demand gives local producers a testing ground that many African peers lack.

Sectorally, agro-processing clusters are expanding across states like Ogun and Kaduna, turning raw agricultural output into value-added exports. Meanwhile, the creative economy (film, fashion, beauty) is positioning Nigerian SMEs as cultural exporters with continental appeal.

The fintech ecosystem is also a quiet game-changer. From digital payments to trade financing, Nigerian platforms are bridging gaps in SME credit and enabling cross-border e-commerce flows, narrowing some of the competitiveness deficit with Kenya.

By 2027, Nigeria could emerge as AfCFTA’s consumer hub, leveraging its scale and fintech infrastructure. But without tackling infrastructure and regulatory blind spots, it risks being a market for others, rather than a leading supplier.

Read also: What Africa must do to unlock market potential for MSMEs

Investor, market implications

For investors, AfCFTA is as much about timing as it is about sector focus. Nigeria’s scale offers unrivaled opportunities, but the smart bets will be on agro-processing, fintech, and light manufacturing. Agro-processing, particularly in cassava, cocoa, and palm derivatives, offers the chance to move up the value chain from raw commodities to export-ready products. Fintech remains the backbone of SME trade enablement. Digital payments, credit scoring, and cross-border settlement are high-growth areas. Light manufacturing—textiles, packaging, and consumer goods—has strong regional demand if costs can be managed.

Yet, risks loom large. FX volatility remains a profitability killer, while policy reversals and regulatory opacity have derailed promising ventures in the past. Navigating Nigeria still requires deep local knowledge and active risk management.

For bold investors, underserved export niches—processed foods, fashion, and digital services—offer asymmetric upside. But the rule is clear: avoid overexposure to heavily import-dependent models and anchor strategies in Nigeria’s domestic demand base.

In the AfCFTA framework, success will hinge on aligning with resilient sectors, adaptive SMEs, and reform-driven enablers. Nigeria won’t be the easiest bet—but for those who get it right, it could be the most rewarding.