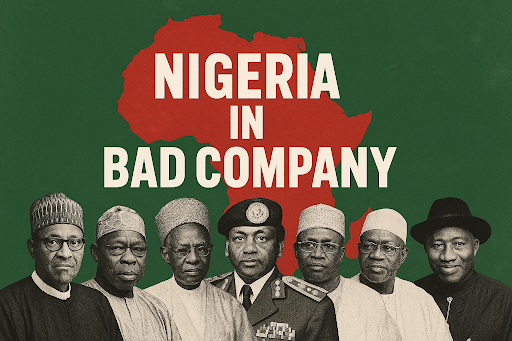

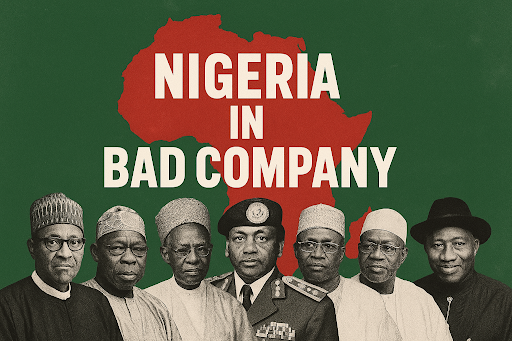

Nigeria prides itself as the “Giant of Africa.”

While there is no official declaration nor a precise year when this title was conferred, the moniker emerged in the early 1970s, when Nigeria blossomed as Africa’s wealthiest nation—especially after the 1973 oil crisis. The country enjoyed unprecedented growth, so much so that General Yakubu Gowon was quoted as saying, “Money is not the problem, but how to spend it.”

One is left to wonder: was it this very lack of ideas on how to spend our wealth that birthed the troubles bedevilling us today—exponential population growth without planning, corruption in procurement and governance, and decades of squandered opportunities? When the use of a thing is not known, abuse is inevitable. Perhaps this is why Nigeria now features prominently—sometimes even leading—in some of the worst global development rankings.

Let’s dive in to review the bad company we currently swim in.

Health, Education and Nutrition: The Human Capital Crisis

If a nation’s wealth is its people, then Nigeria is running on a bankrupt account. Today, we hold the unenviable record of the lowest life expectancy in the world—about 54 years—and the highest maternal mortality, with a woman dying every seven minutes during childbirth. I am shocked at this record, and I am quite certain many of my readers would be. It’s quite despicable that living in Nigeria is the greatest risk to life even greater than living in Afghanistan. These grim statistics are not the result of divine punishment, but of decades of underinvestment and policy neglect. Hospitals are under-equipped, health workers are underpaid and emigrating in droves, while primary healthcare—the bedrock of any system—remains weak. That horrible picture of the hospital in Kangiwa, Kebbi state easily summarises the ‘’state of art ‘’ care available in our general hospitals.

Education fares no better. Nigeria is home to over 10 million out-of-school children, the highest number globally. Classrooms are overcrowded, teachers poorly trained, and strikes by academic staff have become routine. Yet rather than confront these structural basic issues, there has been a plan to incorporate practical and technical skills like IT and entrepreneurship, and emphasize STEM education for primary and secondary students, beginning with the 2025/2026 academic session- this September. I mentioned on a X space – ‘’it is a policy somersault. You don’t have schools but you’re talking about what you’re going to teach them in schools’’.

To compound this crisis, Nigeria now carries the heaviest burden of food insecurity in the world, with over 31 million citizens facing hunger. In a land blessed with fertile soil and vast arable land, millions are trapped in malnutrition, children grow up stunted, and adults lose productive capacity. Hunger makes learning impossible, weakens the body against disease, and deepens poverty cycles. That such a basic need is unmet reflects not a shortage of resources, but the failure of governance to turn Nigeria’s natural wealth into nourishment for its people.

Taken together, these realities paint a damning picture: Nigeria ranks worst in global life expectancy and maternal mortality, leads the world in out-of-school children, and now tops the chart for food insecurity. These three “bad records” strike at the very core of human capital—health, education, and nutrition—without which no society can dream of meaningful development.

Infrastructural Decay

In electricity, Nigeria is the world leader in deficits: in 2023, 86.8 million people lacked access, the highest number globally for the third consecutive year. Only about 61% of the population had electricity and even connected households received an average of just 6.6 hours per day. While installed capacity is around 13,000 MW, only a fraction—roughly 4,000–6,000 MW—actually reaches homes, leaving millions reliant on costly fuel generators.

Roads tell a similarly sad story. Nigeria has approximately 195,000 kilometres of roads, but over half are in poor condition, particularly in rural areas. Adjusted for population and land area, road density is low, and Nigeria’s road network ranks well below global standards, leaving it in the same league as countries often considered less developed. Poor roads impede trade, increase transport costs and risks of mishaps, and isolate communities, making economic development slow and expensive. Nigeria’s rail network spans about 3,798 kilometres, placing it far behind other African nations like Kenya or Ethiopia when adjusted for population and economic size. Rail projects are expensive and slow: the Abuja–Kaduna line cost roughly $4.4 million per kilometre, while Ethiopia’s Addis Ababa–Djibouti electrified railway was completed at a lower cost per kilometre despite being double-tracked and modernized. This shows inefficiency in both planning and execution, limiting the impact of rail infrastructure on national development.

Together, these figures tell a story of stagnation. With unreliable electricity, crumbling roads, and an underperforming rail network, Nigeria struggles to move goods, sustain businesses, or provide basic services efficiently. This infrastructural decay keeps the nation in bad company, alongside countries often seen as “less developed,” and it is a major reason why economic growth and social progress remain painfully slow.

Governance and living standards metrics

Nigeria’s governance crisis is evident in the daily lives of its citizens. With a rank of 116th globally on the 2025 Chandler Good Governance Index, the country struggles with weak leadership, fragile institutions, and poorly enforced legal frameworks, placing it firmly among nations with deep governance deficits. Poverty is widespread: as of 2023, nearly 39% of Nigerians—about 87 million people—live below the poverty line, very much recognised as the poverty capital of the world. These figures are not most numbers; they represent millions of families trapped in cycles of hardship with limited access to opportunity.

Human rights protections in Nigeria are extremely poor. The country scores only 3.2 out of 10 on the Human Rights Measurement Initiative’s “Safety from the State” metric, signalling a high risk of arbitrary arrest, disappearance, torture, and other violations. Citizens are often forced to live as second-class residents in their own country, with internally displaced persons (IDPs) scattered across camps and temporary shelters—over 3.5 million people remain displaced, many without access to basic necessities. Stories of Nigerians fleeing to other African countries illegally- Ghana, Benin Republic, South Africa, Libya etc, seeking safety and opportunity abroad, have become all too common. NIDCOM has been returning them, hopefully the situation at home won’t make them wilfully go back to captivity.

Remember that young woman, Mercy Oluwagbenga, rescued from Libyan captivity? She was driven by away by extreme poverty, including lack of basic health care for her ailing mum. She eventually lost her mum to the cold hands of death despite that much suffering in Libya. A very sad story. One could perceive the regret in her voice, the sadness in her face and the broken heart with which she delivered her experience. Mercy’s situation highlights the extreme exploitation that citizens endure when their own country fails to protect them.

Written by Dr Tolulope Ogunmuko – Teeboi001@yahoo.com