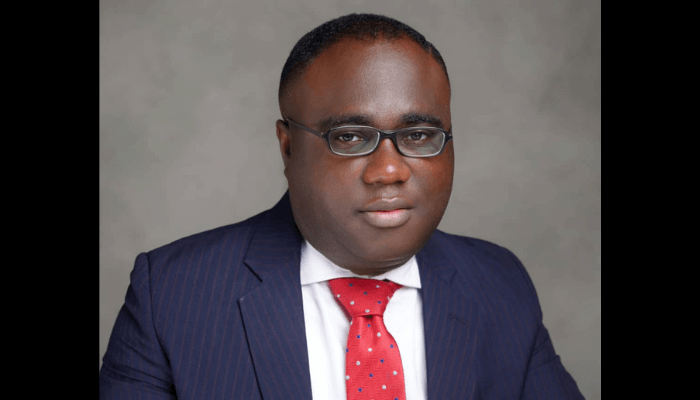

BusinessDay’s Go Local initiative spotlights Nigerian enterprises that harness local resources to create world-class products and services across fashion, food, manufacturing, agriculture, technology, and other industries, redefining innovation, generating jobs and strengthening Nigeria’s economic resilience. In this edition, we turn to the foundation upon which every thriving sector rests – energy. Ayodele Oni, Partner at Bloomfield Law and one of Nigeria’s foremost experts in oil, gas, and power, shares insights on how reliable energy can unlock the full potential of local industry and drive inclusive growth. He spoke with Stephen Onyekwelu. Excerpts:

From your vantage point advising on oil, gas, and power projects, how can Nigeria’s energy sector become the true enabler of local economic growth, particularly for small and medium-scale enterprises?

Picture a bustling market or a small food-processing unit that loses half its stock each season because power is unreliable and diesel is expensive. That’s Nigeria’s missed opportunity – our energy resources should do more than fuel exports, they should fuel businesses, jobs and local resilience.

With the Electricity Act 2023 (the “Electricity Act”) now giving states power to regulate their own electricity markets, there is a clear chance to localise solutions that directly serve small and medium-scale enterprises (“SMEs”). Yet, many of these enterprises are still trapped, spending more on fuel than on business growth, while agro-processors lose harvests because there is no steady power for cold storage.

The most viable way to change this is by supporting targeted energy solutions catering to SME clusters such as markets, industrial parks, ICT hubs and farms, etc. Mini grids, embedded gas plants and solar-hybrid systems, if linked to these clusters with fair tariffs and clear rules, can cut costs and raise productivity. To achieve this, regulators must create frameworks allowing flexible tariffs for productive use and also approve private projects that serve these clusters.

For the oil and gas industry, the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) already provides for domestic gas delivery obligations; it is key that this is adequately enforced and prioritised, particularly for SMEs, by ensuring that there is adequate feedstock. Finance is also a very important aspect of this enablement.

Energy projects for SMEs mostly fail because banks think they are too risky, but this can change if the government steps in with loan guarantees and local currency bonds that lower the risk for investors. At the same time, local energy service providers must be given space to thrive as they are more acquainted with local energy needs and can create tailored solutions. Again, I must state that if Nigeria begins to measure success in the oil and gas sector not by export capacity but by business growth and employment, then energy can truly be a driver of the local economy.

You’ve helped shape policy and regulation in Nigeria’s electricity and gas sectors. In your view, where does the real execution gap lie: policy design, implementation, or enforcement?

My view is that the core challenge isn’t so much about crafting policies as it is about their effective implementation and enforcement. Nigeria has made significant strides with robust policy frameworks, such as the Petroleum Industry Act of 2021 and the Electricity Act of 2023.

These laws lay a solid foundation for developing commercial gas markets, expanding state-led and distributed power solutions, and attracting private investments. However, the real impact depends on consistently delivering the fundamental infrastructure and ensuring these regulations are upheld. Without that commitment to effective implementation, even the most comprehensive policies can fall short of their potential.

For instance, despite the express provision of Section 114 of the Electricity Act that mandates metered supply of electricity, many customers in Nigeria still don’t have meters, so power use is often guessed or underpaid. These things reflect negatively on the sector. For instance, in the first quarter of 2025, none of the Discos met their Aggregate Technical, Commercial and Collection losses (ATC & C). Distribution companies still routinely fail to collect a large share of billed revenue, starving generating companies and gas suppliers of cash and forcing repeated government interventions.

For gas, the PIA and the Gas Flaring (Prohibition and Penalties) Regulations already prohibit routine flaring and even created the framework for flare commercialisation projects. The Integrated Operations Directive also clarified the split between the Nigerian Upstream Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) and the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) for integrated gas facilities.

However, as earlier stated, the gap is not policy but enforcement, as many operators still flare because penalties are weakly applied, and flare-to-power projects stall due to unclear midstream access rules, including the absence of fully operationalised network codes and transparent tariffs for third-party access to pipelines and processing plants.

Put simply, what the sector needs at the moment is a clear and enforceable implementation framework. First, metering must be completed so customers pay for what they actually use. Any government support, like debt relief or refinancing, should only go to companies that meet clear performance targets and for a limited time, not an endless bailout. Defaulting companies should also face real consequences as prescribed by law. If these steps are taken, the laws already in place will finally start delivering a steady gas-to-power supply and more investments

Energy infrastructure requires massive capital. What innovative financing structures – local or international – do you see as game-changers for Nigeria’s oil, gas, and power sectors?

One innovative solution already gaining ground is the use of prepayment deals, where investors or trading partners provide cash upfront in exchange for future deliveries of crude oil or gas. For example, Afreximbank recently arranged a multi-billion-dollar facility for Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (“NNPC Limited”) using this model. It is impactful because it delivers quick funding for projects while lenders are repaid directly from the sale of oil, reducing risks of delays or government shortfalls.

Another viable structure is through the use of green bonds, as it has great potential to open Nigeria to large pools of international sustainable finance. Nigeria has already done well in setting up frameworks to accommodate sustainable finance, particularly with the release of the Green Bond Rules by the Securities and Exchange Commission as far back as 2018.

Typically, Green Bonds are issued specifically to fund environmentally friendly projects, such as renewable energy plants, cleaner gas-to-power facilities, or grid upgrades that reduce emissions. What makes them powerful is not just the cheaper cost of capital they attract, but also the credibility they bring.

Investors know their money is tied to climate-positive projects because the bonds are backed by transparent reporting and often verified by independent bodies. Nigeria has already issued sovereign green bonds, setting a precedent that private companies and state utilities can build on. If scaled, this instrument could provide a steady flow of long-term capital for the country’s energy transition while positioning Nigeria as a credible player in the global shift to sustainable investment.

Another option will be the securitisation of future energy revenues. This works by packaging predictable cash flows into tradable securities that investors can buy. The proceeds are then used upfront to expand or stabilise energy infrastructure. The impact of securitisation lies in unlocking capital from assets that are already generating income.

For example, a distribution company could securitise part of its expected tariff could securitise part of its expected tariff collections, with safeguards like escrow accounts and credit guarantees to reassure investors. Although not as common in Nigeria, securitisation will not only bring in new financing without adding traditional debt, but will also encourage investments, as it is tied to real infrastructure performance

Nigeria has abundant gas reserves, yet industries and households still struggle with access. How can we accelerate gas utilisation for both domestic energy security and industrialisation?

Nigeria has always recognised gas as its transition fuel and has launched several well-meaning initiatives such as the Decade of Gas initiative, the National Gas Expansion Program and the Gas Flare Commercialisation Programme, among others.

However, to really turn these policy declarations into bankable projects that connect reserves to demand, there is a need to prioritise modular solutions such as Compressed Natural Gas (“CNG”) and mini-liquified natural gas (LNG) hubs, virtual pipelines and gas aggregation centres.

These smaller-scale systems can be rolled out quickly to bring gas closer to industrial clusters and commercial locations. Encouragingly, the government has already taken a strong step with the Presidential CNG Initiative, which signals a high-level commitment to gas-based solutions for households and industries. But for real scale, Nigeria needs an influx of private sector participation and capital to replicate and expand gas projects nationwide, ensuring that gas is not only produced in abundance but also delivered efficiently to the end-users who need it most.

There is also a need to encourage domestic companies involved in the production and supply of gas, as they are more acquainted with the gas demands of their local communities, and can provide tailored solutions and deliver gas to the end users who need it most.

Lastly, building financial certainty around gas demand is also critical to demand as it enables investors to confidently back gas-based projects. Large industrial users such as cement plants, fertiliser companies and refineries should commit to firm supply contracts, for example, take-or-pay agreements, which guarantee minimum purchases even if full volumes are not used.

You advised on Nigeria’s post-privatisation power sector restructuring. Looking back, what worked, what failed, and what reforms are still urgently needed?

In retrospect, I see Nigeria’s power sector privatisation as the starting point for building a more market-oriented industry. The process of breaking up the Power Holding Company of Nigeria (PHCN) into Generation Companies (“GenCos”) and Distribution Companies (“DisCos”) paved the way for private ownership and increased competition.

At the same time, institutions like the National Electricity Regulatory Commission stepped in to establish the regulatory framework that was previously absent. This combination of structural reform and new oversight has laid the groundwork for a more dynamic and sustainable energy sector.

I strongly believe post-privatisation is still a work in progress, although I must state that there are issues that need to be addressed. DisCos still struggle with high losses, poor collections, and limited investment in their networks, leaving large metering gaps. Tariff shortfalls and weak payment discipline have created systemic arrears across the value chain, while transmission bottlenecks, vandalism, and poor gas-to-power coordination continue to undermine supply.

There is also a need for effective regulatory coordination. For instance, the recent tariff clash in Enugu, where the state regulator lowered electricity rates but ran into resistance from the local Disco and eventually drew in federal authorities, highlights the cracks in the system. It shows how uncoordinated regulation can worsen the sector’s financial troubles and discourage investors.

What is now required are practical, enforceable reforms. Tariffs must be made cost-reflective, supported by targeted subsidies for vulnerable consumers. The Electricity Act must be fully implemented, including commercialising transmission and clarifying Nigerian Bulk Electricity Trading Plc’s (NBET) evolving role as a market stabiliser rather than as a direct trading partner with GenCos. Furthermore, there should be strict enforcement of applicable laws to ensure DisCos meet metering targets.