When 32-year-old market trader Zainab Musa fell ill with malaria last year, she had to borrow N18,000 to pay for drugs and hospital tests, nearly half her monthly earnings.

“I don’t have insurance. Everything I pay is from my pocket. If I don’t sell, I can’t go to the hospital,” she said quietly.

Musa’s story mirrors that of millions of Nigerians who still pay for healthcare out of pocket. More than seven in 10 citizens fund their medical expenses themselves, turning illness into both a medical and financial crisis.

Those covered by health insurance, however, spend up to 80 percent less on hospital care, a stark reminder of what protection means in a country where over 90 million people live below the poverty line.

A promise still out of reach

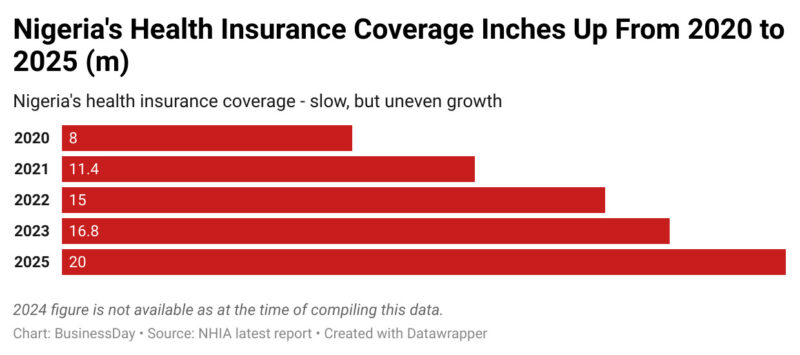

In September 2025, the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) announced that 20 million Nigerians were now covered, up from 16.8 million in 2023. Progress has been made, but it still leaves more than 90 percent of the population uninsured, particularly those in the informal sector and rural areas. Poverty, distrust, and inefficiencies have kept millions locked out.

The Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), the main federal vehicle for subsidising care for the poor, was designed to bridge that gap, alongside equity funds from state governments. But a 2024 report by the WellaHealth Foundation revealed that more than half of Nigeria’s State Health Insurance Agencies (SHIAs) failed to release their equity funds despite budgetary allocations.

Read also: More than half of Nigerians lack access to affordable, quality healthcare — Report

According to the State of States Health Insurance Report 2024, 52.8 percent of SHIAs did not disburse the funds meant to subsidise care for vulnerable groups, including pregnant women, children under five, and the elderly.

The shortfall is staggering. Legally, all states except Kogi and the FCT, have laws backing equity funding. Yet only 19 states made releases in 2024. Delta led with N1.89 million, followed by Jigawa (N173,030) and Kaduna (N79,329). States such as Anambra, Rivers, Benue, Kwara, and Zamfara released nothing, according to the report.

Behind these figures are real lives. In states where equity funding stalled, many delayed or abandoned treatment altogether. A recent NBS survey found that medical costs now account for over 15 percent of household expenditure in poor families, a burden that deepens poverty.

Health economists estimate that if states had fully released their funds in 2024, at least 10 million more Nigerians could have been covered under subsidised schemes. Instead, only about 2.5 million were enrolled through the BHCPF.

A radical idea: The five kobo health revolution

As traditional funding channels falter, some experts are looking elsewhere for solutions and one proposal stands out for its simplicity and ambition.

Bode Karunwi, a Nigerian dentist and health entrepreneur, believes that the telecommunications sector, which has transformed Nigeria’s digital landscape and generated trillions in revenue, could play a pivotal role in reviving the country’s collapsing healthcare infrastructure.

“We saw how liberalising the telecoms sector changed Nigeria forever, from less than 500,000 landlines under NITEL to over 150 million mobile subscribers today. We can replicate that success in health, through smart, technology-driven funding,” Karunwi told BusinessDay.

His model, dubbed the ‘Five Kobo Health Revolution,’ proposes a micro-levy of N0.05 (five kobo) on every second of voice calls made across Nigeria’s four major telecom operators: MTN, Airtel, Glo, and 9mobile.

With over 150 million active mobile lines, according to the Nigerian Communications Commission (NCC), and Nigerians spending billions of minutes daily on voice calls, the projected returns could be transformative. “A small levy that no one feels individually could raise as much as N2 trillion annually. That is more than four times what the federal government allocates to health today,” Karunwi explained.

Read also: A syringe for a life: How poor health facilities cost lives

He noted that MTN Nigeria alone earned N3.73 trillion in the first nine months of 2025, underscoring the vast financial potential of a telecom-linked health fund.

How it would work

Under the proposal, the funds generated would go directly into the National Health Insurance Authority (NHIA) pool, used to cover premiums for citizens who are not currently insured, especially in rural areas and among low-income households.

The levy would be collected automatically by telecom operators and remitted monthly, just as the NCC already manages the Universal Service Provision Fund (USPF) to expand rural connectivity.

Citizens could register for coverage through a mobile app or USSD code linked to their National Identification Number (NINs) or SIM cards and an independent National Health Regulatory Commission, modeled after the NCC, would oversee disbursements, quality standards, and consumer protection. “If the NCC can regulate 150 million telecom users efficiently, we can build a similar transparent system for healthcare access,” Karunwi said.

Why it matters

Nigeria’s healthcare sector currently receives less than five percent of the national budget, far below the 15 percent target set in the 2001 Abuja Declaration. Out-of-pocket spending remains dangerously high, with over 70 percent of total health expenditure, pushing millions of families into poverty every year.

By contrast, the telecom sector is one of the country’s most stable and lucrative industries. According to NCC data, the sector contributes about 14 percent of GDP, generates over N20 trillion in annual turnover and employs millions directly and indirectly. “The same private-sector dynamism that made phone calls accessible to everyone can make healthcare accessible to everyone,” Karunwi emphasized.

The long-term vision extends beyond funding to digitising healthcare, creating a mobile-based, consumer-friendly insurance system similar to mobile banking.

Each user would be able to check their insurance status and benefit package in real-time, locate approved clinics or hospitals nearby, switch Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs) as easily as porting between networks and file complaints or rate service providers digitally.

This system, Karunwi argued, would reduce corruption, eliminate ghost enrollees and improve service accountability. “You will be able to see where every naira goes, just like you can track airtime or data use. Transparency will drive trust and efficiency,” he added.

Stakeholders react

Akin Abayomi, Lagos state health commissioner, told BusinessDay the five-kobo levy aligns with Lagos’ push for innovative domestic financing. “Pooling micro-contributions from large populations is a practical, equitable way to close Nigeria’s health financing gap without overburdening citizens,” he said.

Njide Ndili, country director for PharmAccess Nigeria, called it a bold, forward-thinking idea that could transform healthcare financing. “It reflects the growing consensus that sustainable health funding must come from locally adaptable, technology-driven models,” she said.

Ayo Adebusoye, chairman of the Public Health Sustainable Advocacy Initiative (PHSAI), also hailed it as one of the most innovative public–private health financing ideas in recent years. “If implemented effectively, Nigeria could achieve universal health coverage within five to seven years,” he added.

But not everyone agrees

But Gbenga Adebayo, chairman of the Association of Licensed Telecommunications Operators of Nigeria (ALTON), strongly opposed the idea.

“I disagree completely. Why should telecom services, which have already become a social impact utility, be taxed again? The average Nigerian pays multiple taxes on almost everything they buy today. Every item, except food, attracts VAT. Salaries are taxed under PAYE. All these revenues are supposed to be used to fund the health sector,” he told BusinessDay.

Adebayo argued that another levy would burden consumers and undermine digital inclusion drives. “Why should somebody suggest that the government should come after telecom services again to fix the health sector? It is unfair to the industry and to subscribers,” he added.