…Arrears distort state balance sheets, discourage investment – Analysts

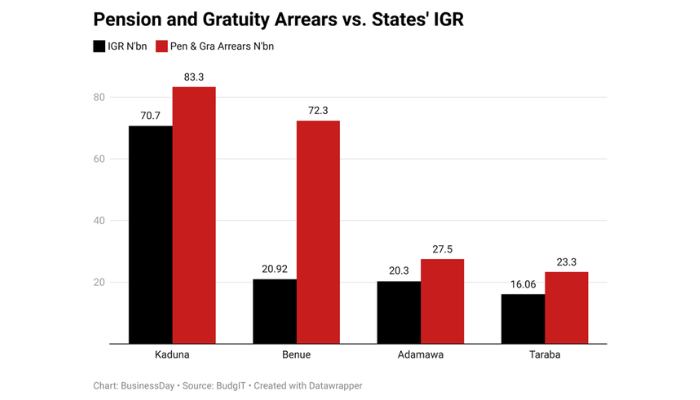

The pension liabilities of Kaduna, Benue, Adamawa and Taraba surpassed their Internally Generated Revenues (IGRs) in 2024, highlighting the fiscal distress facing these subnational governments.

According to BudgIT’s ‘2025 State of States’ report, the four states collectively owed more in pension and gratuity arrears than they generated internally – a troubling imbalance highlighting years of weak planning and heavy reliance on federal allocations.

The combined pension arrears stood at over N206 billion, compared with a total 2024 IGRs of N127.98 billion.

Kaduna tops the list with N83.3 billion in pension arrears against N70.7 billion in IGR. Benue follows with N72.3 billion pension debt, while generating only N20.9 billion internally. Adamawa’s N27.5 billion liability surpasses its N20.3 billion revenue, just as Taraba owes N23.3 billion well above its N16.06 billion IGR.

The human impact of pension arrears

The crisis is not abstract. It is mostly felt by pensioners who, after decades of public service, are left waiting indefinitely. In Benue, where repeated fiscal breakdowns have become routine, the frustration is palpable. “Many of our pensioners have died waiting,” a civil servant in Makurdi said, reflecting the despair among retirees who have gone months or years without the benefits they are owed.

The Nigeria Labour Congress (NLC) has also raised the alarm about the poor treatment of pensioners in Africa’s most populous nation. “Retirement ought not to be a death sentence,” Joe Ajaero, NLC president, warned at a pre-retirement summit, noting that arrears at multiple tiers of government have eroded the very purpose of the pension system.

The widening North–South revenue gap

The fact that all four affected states are in northern Nigeria points to a broader structural divide. While southern states such as Lagos, Ogun, Enugu and Rivers have steadily grown their IGRs, many northern states remain overwhelmingly dependent on federal transfers. BudgIT data show that Kaduna, Benue, Adamawa and Taraba rely on federal funds for more than 85 percent of their revenues.

Weak local economies, slow reforms, insecurity and poor financial planning have amplified the gap. Pension schemes in these states have been pushed aside for years, with liabilities rolled over rather than properly funded, and no credible sinking funds established, financial analysts argue.

Economic cost and long recovery

The failure to pay pension arrears has consequences that stretch far beyond retirees. Economists say unpaid entitlements reduce consumption, deepen poverty, weaken institutional credibility and may fuel corruption. Younger workers, observing the treatment of retirees, tend to save less and spend cautiously, eroding confidence in the system.

“If a state owes more in retirement benefits than it earns in a year, it’s not just a labour issue, it’s insolvency in slow motion,” said Muda Yusuf, chief executive officer of the Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise (CPPE). He explained that these arrears represent “quasi-debt burdens that distort state balance sheets and discourage new investment.”

To understand the scale of the problem, a BusinessDay analysis estimates how long it would take each state to clear its arrears if 25 percent of annual IGR were devoted solely to pension repayments, assuming stable revenues and no new arrears. The results are sobering: Kaduna would need about five years, Adamawa and Taraba about six years each, while Benue, because of its weaker revenue base, would need roughly 14 years.

This long repayment horizon underscores the gravity of the crisis. For pensioners, it means years more of waiting. For the states, it reveals how deeply unbalanced their finances have become.

Read also: Four northern states now owe more in pensions and gratuities than they earn — BudgIT

What can be done?

Experts say the first step is a proper audit of pension liabilities, combined with full payroll verification and the removal of ghost workers that inflate wage bills. States must also create dedicated pension funds and make consistent payments, even if small, to gradually reduce arrears.

Strengthening IGR through tighter tax collection, digital payments and sector-focused investment is equally vital.

Some progress has been recorded. Kaduna and Taraba have begun automating parts of their systems, but reforms remain too limited to address the scale of the challenge. High-burden states such as Benue and Adamawa require stronger fiscal discipline, improved coordination and clearer long-term strategies to restore stability.

The federal regulator’s position

At the federal level, regulators acknowledge the bottlenecks slowing pension payments, particularly accrued rights and delayed remittances by government entities. Omolola Oloworaran, director-general of PenCom, recently noted that “challenges remain in accrued rights and transition issues,” even as the commission works with ministries and agencies to improve compliance and cash flow into retirees’ Retirement Savings Accounts (RSAs).

Her comments highlight that the pension crisis is not exclusive to states, but part of a wider national pattern of underfunded obligations.

Beyond the numbers

BudgIT’s findings make one point clear: pension arrears are not just audit entries; they are broken promises. For many in northern Nigeria, the debts represent years of neglect and short-termism. Without urgent reforms, the next generation of workers may retire into the same uncertainty that today’s pensioners face.

“The cost of inaction is rising. For these states, the longer the delay, the harder it will be to rebuild trust and restore financial stability,” said an Abuja-based economist.

Read also: Twenty-eight states owe retirees N626.81bn in unpaid pensions, gratuities

Ike Ibeabuchi, an emerging markets analyst, urged states to explore ways of raising more revenues.

“States must diversify their revenue sources, but they must also manage their earnings properly. Owing pensioners is a sign of fiscal indiscipline and discourages investment.”