The Federal Government has reversed the National Language Policy, which stipulates that the language of instruction in early childhood to primary school (up to Year 6) be the mother tongue or the language of the immediate community.

In 2022, the Federal Government of Nigeria approved a National Language Policy (NLP), which provides that from Early Child Care Education to Primary 6, the language of instruction will be in the mother tongue or language of the immediate community.

The policy aims to promote indigenous languages, recognise their equal status, and improve early childhood learning outcomes, while English remains the official language used in later education and formal settings.

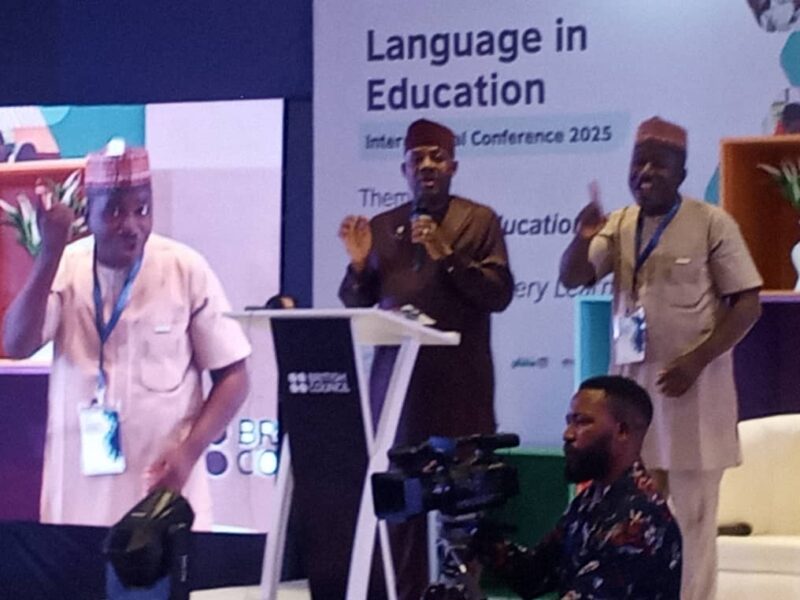

However, speaking Wednesday in Abuja, at the opening ceremony of the Language in Education International Conference 2025 organised by the British Council, Minister of Education, Dr Maruf Tunji Alausa, said English is now the language of instruction in Nigerian schools- from primary to tertiary levels.

Alausa said Nigerian children have been performing abysmally in public exams as a result of being taught in the mother tongue, saying evidence-based, data-driven research by the ministry has shown destruction of the education system because of learning in the mother tongue as pupils and students proceed to higher classes without learning anything.

He said: “The National Policy on Language has been cancelled. English is now the language of instruction in our schools- from primary to tertiary levels. As you know, one of the most important and powerful things in education is language. That’s how the role of language instruction is going to be developed in all subjects.

“The language policy in Nigeria states that mother tongue language will be used in the early stage of primary school, primary one. But then, we’ve seen significant over-supervision into geopolitical zone of the country, and no use of that policy in other forms of geopolitical zones.

“So we reviewed the data available to us, is it really working for us, teaching in the mother tongue? The unanimous outcome of our review, which is evidence-based, data-driven, compared, and now combined with real-life situations, is what we see in the geopolitical zones, where there’s over-supervision, over-use of this mother tongue language, right from primary one to primary six, JSS one to JSS three.

“We’ve seen total destruction of Nigeria’s system, and I use that word carefully, where children graduating from school, finishing up to JSS 3, and even SS 3, they haven’t learnt anything. They’ve gone to do their national exams, WAEC, JAMB, NECO, and they’re failing.

Exams are conducted in English, but we taught these kids through their education in the mother tongue. Also, we have a lot of peculiar situations in other parts. You go to Borno State, for example, in that region, the mother tongue language is Hausa.

“A larger part of people in Borno State do not speak Hausa, they speak Kanuri. You come to Lagos, my home state, and go to areas like Ajegunle, where you have predominantly people from the south-eastern part of the country, but 90% of our teachers are from the south-western part of the country. So we have a unique, God-given diversity.

“We love the challenge of ethnic diversity and language diversity, but then the mother tongue as a language of instruction in a foundational school, we tested it for 15 years, it hasn’t worked, and that’s why we made it strong, to do away with it and we went back to what we were doing 15 years ago, English as a medium of instruction.”

He added: “We have evidence that if we teach students in their mother tongue, especially in the early, pre-primary school, and the first three years, they do better. But then, let’s now look at the context of implementation and the result that we’re seeing, and that’s what this conference is all about.

“This conference is so critical, apt and germane. We need to get it right, and know what medium to use. As I said, earlier, because of the importance of language in education, we now need to really decide what’s the best language for us to use as a medium of teaching in our schools. Also, we’re talking about inclusivity. Inclusivity doesn’t mean getting people who are disabled, or who are physically or mentally challenged into the system. We also have to look at inclusivity in a broader context. How do you get the maximum number of people in school learning, getting the highest quality of education?

“As I said, the bedrock of that is the medium of teaching. And that’s why language in education is extremely important in what we have to do. In fact, that’s the beginning of education. That’s why we need to get it right, and we all need to be on the same page, so that we can deliver the highest quality of education that we hope to deliver in Nigeria, and also talk to other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Also speaking, the Director, English Programmes, Sub& Saharan Africa, Julian Parry, said the conference is to ensure that every learner, regardless of their language background, has an important human right, which is education.

She said: “This conference’s last-minute event is part of a long-standing dialogue to explore the vital questions. How can we ensure that every learner, regardless of their language background, has an important human right? We are proud to be convening this dialogue here in Nigeria – a country whose linguistic diversity is both a challenge and a challenge. But this is not just a Nigeria conversation.

“Over the next two days, we’ll be meeting with colleagues across Africa, South Asia and the UK. We’ll explore how you can help us with navigating the complex conversations between local languages and English. We’ll be examining how language positives are actually being implemented in our communities, and we’ll be discussing how we’re doing things in terms of ethics, development and innovation.

“This international exchange is one of the most powerful aspects of this type of conference, because while every context is different, the questions we face are often similar. How do we train teachers to teach in languages other than English? How do we build teachers at the level of discipline and confidence they need to successfully. How do we provide the resources needed to teach and to learn? How do we assess learning capability across countries? How do we ensure that no child is left behind because of the languages they speak at home and outside school?

“How do we ensure that the outcomes of this conference will help a disabled girl in a particular region of Nigeria with limited access to education? To start answering these questions, our aim over the next few days is simple but ambitious. To share evidence from multiple contexts around the world, to strengthen collaboration, and start a conversation that will help us reach those people all over the world where everybody, regardless of their language background, can participate.

“Over the next two days, we’ll hear from leading voices in education and language policy. For example, this morning the Ministerial panel will explore the role of language in achieving an inclusive and equitable process of education and sustainable development.

Sustainable development by the way of thought.

“What we are, and what we’ve always been, is a trusted partner who works alongside governments and institutions to help them achieve their own education goals drawing from their experience in multiple contexts. We do this by rolling out evidence, by sharing insights from over 100 countries, and by listening carefully to what works, and what might not work, in each unique context.

“Language in this context is not an ideological background. It is a practical, pedagogical, and policy. What ought to go for the school’s purpose? What amounts of learning and disability to access the curriculum in the way it should be? Language ensures a means to inclusion, not an end in itself.”

Speaking earlier, the Country Director, British Council, Nigeria, Donna McGowan, said the conference will provide stakeholders the opportunity of improving English language proficiency as well as administering different English language testing solutions as it brings together policymakers, educators, researchers and partners from across Africa, South Asia and the UK to explore how language can support inclusion and improve learning outcomes across education systems.