1

LAGOS – With more than 86 percent of Nigerian households lacking access to safely managed drinking water, experts are warning that the country’s growing tilt toward water privatisation could deepen inequality, heighten public health risks, and worsen climate vulnerability for millions already living on the edge of thirst.

At the 5th Africa Week of Action Against Water Privatisation in Lagos, scholars, policy analysts, and campaigners from across the continent issued a stark message, stating that privatizing water; the very essence of life could become Nigeria’s final betrayal of the poor.

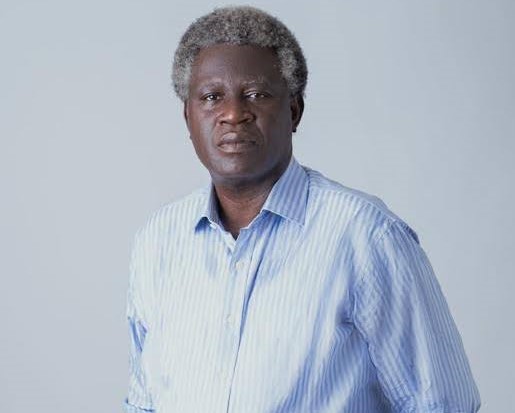

Setting the tone, Prof. Adelanwa Odutola Odukoya, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Lagos, warned that privatisation was “wired to produce poverty, inequality, and exploitation,” describing it as part of what he termed “disaster capitalism.”

According to him; there is water everywhere, but none to drink. “We now have water kidnappers and water bandits, both local and international,” he said. “It is because of them that we are here, so that their nefarious activities which compromise life can be addressed.”

Prof. Odukoya traced the crisis to the influence of international financial institutions that, he argued, “market privatisation as a development model” in Africa.

According to him, institutions like the World Bank and the IMF have for years promoted policies that push African states toward handing over essential public services to private interests, often under the guise of reform.

“The capitalist order that profits from people’s deprivation is at the root of this,” Odukoya said. “Even in capitalist countries, nationalisation of water is returning. Climate resilience cannot and is not compatible with privatisation. We must deprivatise because it denies people access and impoverishes them.”

He described water justice as inseparable from environmental justice and democracy itself.

“Privatisation says if you cannot pay for water, you perish,” he added. “But water is a common good. It belongs to everyone. The people own it. Democracy is about the people, therefore, water must remain a public good.”

Odukoya called for a continental front for public water, arguing that communities and workers should be empowered as co-managers of the resource.

“Water must be recognised as central to life and climate adaptation,” he concluded. “We must end corporate control of African water.”

For Zikora Ibeh, Assistant Executive Director at the Corporate Accountability and Public Participation Africa (CAPPA), the issue is both moral and existential.

“Water is not just a resource, it is life itself,” she said. “Yet, in a country where over 86 percent of households lack access to safely managed drinking water, Nigeria’s growing flirtation with privatisation risks pushing millions beyond the edge of thirst.”

Ibeh warned that treating water as a commodity instead of a public good could “become the final betrayal of the poor in a nation already gasping under inequality.”

The context is grim. According to the United Nations, Nigeria faces one of the steepest water access gaps in Africa, with rapid urbanisation, pollution, poor infrastructure, and erratic power supply compounding the challenge.

Yet, even as communities battle unsafe water, private sector proposals from Lagos to Abuja, have intensified, promising efficiency but raising fears of exclusion for the poor.

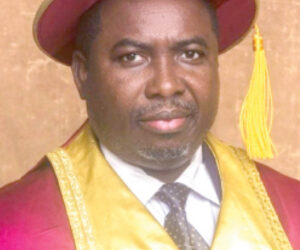

In his opening remarks at the event, Akinbode Oluwafemi, Executive Director of CAPPA, said the “growing pressure to privatise water systems and hand control of this essential resource to profit-driven corporations” was alarming.

“At a time when we need stronger, publicly accountable systems to guarantee universal access, we are seeing governments yield to corporate interests,” he said.

“While nature cries for justice in the face of the climate emergency, capital smells opportunity.”

Oluwafemi argued that multinational corporations were “peddling desalination and other privatisation schemes as climate solutions, selling back to us the very water that belongs to the people.”

He described the theme of this year’s week of action, ‘Public Water for Climate Resilience’ — as a call to defend public ownership and democratic management of water utilities, particularly as climate shocks worsen droughts, floods, and displacement across Africa.

“The resistance against the commodification of water is not an isolated struggle,” he said.

“It is part of a broader continental affirmation that public services, when transparently managed and democratically governed, form the foundation of social justice and climate resilience.”

Adding an international perspective, Neil Gupta, Water Campaign Director at Corporate Accountability (U.S.), said the crisis was driven by an “entire industry that aims to exploit humanity’s need for water to profit.”

“Multibillion-dollar corporations and their wealthy shareholders, mostly based in the Global North, have made riches from privatising community water systems across the globe,” Gupta said.

“They see the Global South — and Africa in particular — as theirs for the taking.”

He cautioned that even so-called public-private partnerships are forms of corporate control, explaining that privatisation shifts the focus from universal access to profit maximisation.

“This is why, in country after country, water privatisation is followed by unaffordable tariff hikes, labour abuses, and cost-cutting,” he added.

Gupta named French corporations Veolia and Suez as “the largest multinational water privatizers in the world,” accusing them of leaving “a decades-long track record of abuse in their wake.”

He also highlighted the role of Global North governments and financial institutions, including the World Bank, IMF, and even the French state, which he said was “one of the largest shareholders” in Veolia and Suez.

“From Lagos to Kenya and Gabon, Global North institutions are entangled with the water-privatising industry,” he said. “They’re using aid and policy leverage to open Africa’s water systems for profit. Building communities’ and workers’ power is the only counterweight.”

Experts say Nigeria’s water challenge mirrors a continental crisis: rapid population growth, mismanagement, and climate pressures are colliding with market-driven reforms that prioritise private capital over public need.

Across Africa, over 300 million people live in water-scarce regions, according to UN data.

While advocates of privatisation argue that it attracts investment and improves efficiency, critics counter that access to water — like education or healthcare is too fundamental to be left to market forces.