On the humid evening of Monday, 29 September 2025, in Otuabagi, Ogbia Local Government Area of Bayelsa State, the faint cry of a newborn briefly lifted the spirits of a community long accustomed to subdued sorrow.

Patience Bulus had just delivered her fourth child after a long night of labour, assisted only by a weak flashlight with dying batteries.

There was no electricity at the Otuabagi Primary Health Centre, no doctor, no midwife, and no proper delivery bed. Her only support came from a volunteer Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW), whose stipend had been owed for over five months.

Twelve hours later, Mrs Bulus bled to death, a preventable tragedy in a state that receives some of Nigeria’s highest allocations from the Federation Account, in a community that helped launch the country into the petroleum age nearly 70 years ago.

Her widower, Bulus John, recounted how his joy at the birth of his child quickly turned into grief.

“I was very happy when the health worker called to tell me that my wife had given birth,” he said.

“She told me to wait for at least an hour before I could come and carry her and the baby. After an hour, I went to pick up my wife and baby. They were all fine.”

But before the community had even awakened, everything changed.

“My wife started bleeding heavily around 4 a.m., the next morning,” Mr John recalled.

He immediately informed Rejoice Raymond, the CHEW, who had assisted with the delivery. Realising that the situation, which she suspected was a postpartum haemorrhage, was beyond her capacity, Ms Raymond immediately referred Mrs Bulus to a doctor at the hospital in Ogbia town, the local government headquarters.

At the hospital, a blood transfusion was administered, but it failed to clot the blood flow.

“After observing that the situation remained the same, the doctor recommended that I take my wife to the Federal Medical Centre in the capital city, Yenagoa,” he said.

Mr John spent hours looking for a vehicle before finally reaching the hospital, where, tragically, his wife died.

Carrying his wife’s lifeless body back through the same journey that had earlier held hope, Mr John confronted a reality shaped not by chance but by the priorities set far from Otuagbagi, in the air-conditioned offices where budgets are written and resources allocated.

“If doctors were here, I don’t think she would have died because there would have been a prompt and immediate action,” Ms Raymond, the health worker, told PREMIUM TIMES.

Mrs Bulus is not the only pregnant woman to fall victim to a preventable death in Otuabagi.

Ms Raymond, the CHEW, recounted a story of Thank-God Dagogo, who died in November 2024 due to internal bleeding from a suspected ectopic pregnancy.

“Thank-God had a shortage of blood because she was bleeding internally. Before she could be referred to the hospital within the capital city, she was confirmed dead.”

The community that built Nigeria left without care

Otuabagi in Ogbia LGA is one of Nigeria’s earliest oil-producing communities. Yet, seven decades after Nigeria commenced commercial crude oil extraction in 1956, in Ogbia LGA, Otuabagi cannot provide a pregnant woman with even a source of electricity during childbirth.

Doris Egba, a community resident, insisted that there is no justification for the community to remain without a well-equipped health facility and adequate personnel.

“When we have an emergency, we run kilometres to reach the next health centre or hospital in other communities. Due to this, we have lost many of our women,” she said.

“How many women are going to die before the government hears the cry of this community? Oil production has already affected our health with different sicknesses. Now, there is no good health facility.”

When PREMIUM TIMES visited the Otuabagi PHC in early October, the facility was under lock. However, the dilapidated window allowed a view of the nearly empty outpatient department.

According to community reports, the PHC has two community health officers, but both reportedly reside outside the local government area and rarely report for duty.

The facility is left in the care of Ms Raymond, the volunteer CHEW who has served since 2018, often going beyond her legally defined scope to save lives.

“Since there is no electricity, I use a rechargeable touch light. Most times, when I put it on for pregnant women during their birth pangs, before it gets to the delivery point, the light has run down,” Ms Raymond said.

In addition to this, the facility has broken doors, missing windows, leaking ceilings, a lack of mosquito nets, no fence, and an absence of security, making it unsafe for both staff and patients.

Many women, like Mrs Bulus, leave the facility prematurely, exposing themselves to avoidable risks after childbirth.

The situation in the community has worsened amid ongoing strikes by volunteer health workers in Bayelsa, who have not been paid for over five months.

Consequently, the PHC now opens only for emergencies, further discouraging women from considering it as an option.

“When we ask our women to come to the facility for antenatal care, they reject it because there is nothing inside the health facility,” the Woman Leader of the community, Sarah Emiebo, told PREMIUM TIMES.

Ms Emiebo said that since there are no medicines or qualified personnel, women and parents do not visit the health centre; instead, they rely on local remedies and Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs).

Binaebi’s first pregnancy became her final journey in life

The situation in Otuabagi is not unique to the community. Communities in the Sagbama Local Government Area tell a similar story, albeit with different names.

In Bulou-Orua, Binaebi Emmanuel, who had waited six years for her first child, went into labour on 16 July. She arrived at the community health centre, only to be told bluntly: “There is no doctor, nurse, or midwife here.”

With no qualified personnel and no equipped delivery room, Mrs Emmanuel had to travel through multiple communities in search of care. By the time she reached the hospital, she was too exhausted to survive childbirth.

Her story is echoed in the testimonies of community leaders who no longer bother counting their dead pregnant women.

Daniel Smart, the chairman of Bulou-Orua Community Development Committee (CDC), said Mrs Emmaunel’s death is just one among many.

Mr Smart said the lack of qualified manpower and equipment discouraged many pregnant women and other community members from patronising the PHC facility.

“Our people refuse to go there because the place is not functioning properly,” he said.

“Sometimes, they go, and people who should be on duty are not available. Our people now travel to other communities where the facility is functional or the general hospital. But sometimes when there are emergencies which could have been addressed here, people die.”

Beyond the fact that the Bulou-Orua PHC, which serves a population of 8,465, has become overgrown with weeds, the facility lacks basic equipment, including mattresses, beds, electricity, and water.

At the time PREMIUM TIMES visited the facility, Ayibaere Rowland, the only health officer on duty, said the facility had only three staff: a Community Health Officer, and two health attendants, who, by Nigeria’s standard for PHC, are not qualified for midwifery services.

Due to inadequate manpower, Ms Rowland said they only provide antenatal services, saying she could not recall the last delivery handled at the facility.

As a result of this, pregnant women often bypass the PHC entirely, seeking care elsewhere or relying on Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs), with potentially fatal consequences.

In Toru-Angiama, also in Sagbama LGA, the struggle for maternal healthcare mirrors the experience of Otuabagi and Bulou-Orua.

The Chairman of Toru-Angiama Community Development Committee, Who-knows Ayunku, described how the lack of beds, mattresses, medical consumables, electricity, water and qualified personnel has forced many women to rely on TBAs.

“Many of our women visit TBAs, and many women die there,” Mr Ayunku said.

He lamented that the Toru-Angiama PHC was not a better alternative, noting that when women try to use the facility and cannot access the required services, they often never return.

When PREMIUM TIMES visited the Toru-Angiama PHC in October, the officer in charge, Biboere Churchboy, confirmed that the facility rarely handles deliveries.

Ms Churchboy said that although women visit the centre for antenatal care and after birth for vaccines for their babies, the last time a pregnant woman gave birth in the facility was in 2024.

She attributed this to insufficient staffing and a lack of basic equipment.

“The facility has two beds, there is no mattress, no borehole. We go to the river to fetch water to sterilise our equipment,” she said.

“The solar light here powers only the refrigerator for vaccines. No electricity either. Although there are some routine medications, there are no medical consumables to administer treatment. We buy them with our money for people.”

The OIC, who is a CHEW by qualification and not authorised to engage in delivery services, told PREMIUM TIMES that the facility does not have an employed midwife or doctor.

According to documents seen at the facility, the Toru-Angiama PHC is designed to serve a population of 10,095.

However, Ms Churchboy said the facility has only four employed staff: two CHEW, a dentist and a laboratory technician.

She, however, noted that the government had provided four volunteers – a midwife, two CHEWs and one community mobiliser but the volunteers have been on strike for over five months due to non-payment of their stipend.

Children are also victims

The lack of functional PHCs affects not only pregnant women but also children. In Toru-Angiama, Mr Ayunku recounted the death of a baby in August 2025 due to delays and reliance on TBAs.

“The mother, Joy, was first taken to the TBAs because the PHC is not functioning well. When she had a stillbirth, they took her to the health centre, and she was referred to FMC. When the operation was done, the baby came out dead because of the delays,” he said.

Similarly, in Otuabagi, a convulsing pupil was turned away because the PHC had no medication.

Awudumapu Eze, the secretary of Otuabagi Community Women Leaders, who is also a teacher at the community primary school, described how she and other staff had to take the child across multiple communities before receiving care at a private hospital.

“It broke my heart,” she said.

Health Centre that opens once a week

At Gbaran-ama in Kolokuma/Opokuma LGA, the LGA of the state governor, Douye Dire, the PHC operates only one day a week, offering only immunisation services.

The facility, which is dilapidated with a leaky roof, cracked and dirty walls, and overgrown weeds, lacks electricity, potable water, and basic health equipment.

Residents of the community told PREMIUM TIMES that the facility, which has only one staff member, opens only on Thursdays for immunisation, and when it rains, the activity automatically ends, causing the staff to return home.

They said the community relies on the health centres of other communities for their health needs.

Church-ere Wenikorogha, a resident living near the facility, said, “With the way the facility is, we don’t give birth here. We are often directed to other health centres in other communities.”

New PHCs without doctors

Even in PHCs with new buildings, the structure remains hollow shells, beautiful walls filled with emptiness, which confuses construction with care.

In Okoloba town, Kolokuma/Opokuma LGA, PREMIUM TIMES visited the newly constructed Koloba PHC, a well-furnished four-room and large OPD facility said to be completed in early 2025 under the federal government’s Community and Social Development Agency (CSDA) of the Nigeria Community Action for Resilience and Economic Stimulus (NG-CARES).

Despite its modern appearance, the facility lacks basic amenities such as electricity, toilets, running water, and sufficient beds.

Despite the existence of a new PHC, residents told PREMIUM TIMES that pregnant women in the community still patronise TBAs because the facility lacks qualified medical personnel.

According to documents from the facility, the total catchment population of the PHC is 21,673.

Bago Enebiboloemi, a volunteer staff member, was the only person present during the visit. “What I observe is that they believe in the TBAs. Our record for antenatal care is very high, but the delivery rate is low. After delivery, they come for immunisation,” Mr Enebiboloemi said.

He noted that the facility has only three staff members: two Community Health Officers and one recorder. There is no doctor, midwife, laboratory technician or pharmacist.

The situation is no better in Ofonibiri in Kolokuma/Opokuma LGA.

Despite a PHC renovation in 2021, the lack of adequate staff has stalled effective service delivery, forcing many women to rely on TBAs.

When PREMIUM TIMES visited the facility on 10 October, the facility was under lock.

Utakeme PHC in Ogbia LGA, though gated and equipped with some beds and staff quarters, lacks electricity, hindering emergency deliveries at night.

Yet, according to Charity Dressman, a dental surgery technician met at the facility, none of the five staff members are doctors or midwives.

Ms Dressman noted that a volunteer nurse supporting the facility under the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) programme was on strike due to unpaid stipends.

The real cause of preventable deaths

Across the communities visited, including Otuabagi, Bulou-Orua and Toru-Angiama, the pattern is clear: mothers and children are not dying from rare medical complications.

They are succumbing to common, widely treatable conditions such as postpartum haemorrhage, prolonged labour, and undiagnosed ectopic pregnancies. Each of these conditions requires rapid intervention by trained personnel with basic equipment.

A doctor, or even a nurse/midwife within reach, a functional delivery room, essential medications, an equipped health centre, and a working ambulance could have prevented many of these deaths.

The absence of any one of these critical elements leaves women vulnerable and children at risk, turning preventable health emergencies into fatalities.

Govt silent as lives slip away

Repeated attempts by this reporter to obtain explanations from the state’s health authorities met with evasiveness and outright refusal to provide information.

Specifically, on 8 October, this reporter submitted Freedom of Information requests to the Bayelsa State Commissioner for Health, Seiyefa Brisibe, and the Executive Secretary of the Bayelsa State Primary Health Care Board (BSPHCB), William Appah.

The request sought details on interventions carried out by the state government on PHCs and the amount spent on such interventions between January 2020 and September 2025.

While the commissioner acknowledged receipt but did not respond, the Executive Secretary of BSPHCB contacted the reporter to question why the inquiry was being made and insisted that he would not respond.

Subsequent calls in late October and early November for further inquiries went unanswered.

This reporter later sent a formal media inquiry via text message and WhatsApp to the Executive Secretary of BSPHCB, Mr Appah. The inquiry specifically requested details on the number of doctors and nurses/midwives posted to each PHC in Bayelsa, the amount spent by the Governor Diri administration on equipping PHCs, particularly labour rooms, and the steps the state is taking to address the alarming maternal and child health indicators highlighted by the 2023/2024 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS).

The inquiry also invited Mr Appah to provide any additional information he considered relevant to the subject matter.

Instead of offering clarity, the official grew increasingly evasive. Responding to the WhatsApp message, he questioned why the journalist contacted him through the platform. When reminded of earlier unanswered calls, messages, and the FOI request, he remarked: “If I called and told you I will not respond, why not respect my position and still insist on sending me a message?”

Despite the government’s refusal to provide basic transparency, credible sources within the agency confirmed that no PHC in the state has a government-employed doctor.

One of the sources said a few nurses/midwives are in PHCs in urban areas, but most are volunteers.

In all the PHCs visited by PREMIUM TIMES, none had employed staff beyond five. This is far below the 24 recommended by the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA) minimum standards for PHCs in Nigeria.

In a recent interview with PREMIUM TIMES, the Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer of NPHCDA, Muyi Aina, reiterated that it is the responsibility of the state government to revitalise its PHCs and keep them functional.

“It is not the responsibility of the federal government or NPHCDA to revitalise PHCs,” Mr Aina said.

“We develop it, but we don’t own these facilities; they belong to the states and, in some cases, local governments.

The delivery of services at that level is, structurally, by our health system, a responsibility of the subnational government.”

Statistics that confirm the stories

The experiences in Otuabagi and neighbouring communities reflect what national data has warned for years: Bayelsa’s maternal and child health outcomes remain among the poorest in Nigeria, and the gaps continue to widen.

third-highest in under-five mortalities.

The maternal care indicator is disturbing, too. According to the NDHS, the state ranks lowest in the South in the proportion of women who had four or more antenatal care visits during pregnancy, and it has the second-lowest percentage of women who received antenatal care from a skilled provider.

Furthermore, Bayelsa has the second-lowest percentage of live births delivered in a health facility and the third-lowest percentage of births delivered by a skilled provider in the 17 southern states.

Behind these numbers are the stories of mothers like Mrs Bulus, Mrs Emmanuel, Mrs Dagogo and children like Joy’s, which reflect a worsening health system where preventable deaths have become tragically routine.

Govt officials prioritise foreign medical care

Yet, despite this enormous wealth, Bayelsa’s primary healthcare system is severely underfunded.

Analysis of the state’s huge revenue inflow, together with the Budget Implementation Reports of the state indicates that the grassroots health crisis is not the product of an overwhelmed system; it is the result of a misaligned system where the financial lifelines flow upward to political elites while the primary health system, the structure that protects the largest number of people is allowed to decay.

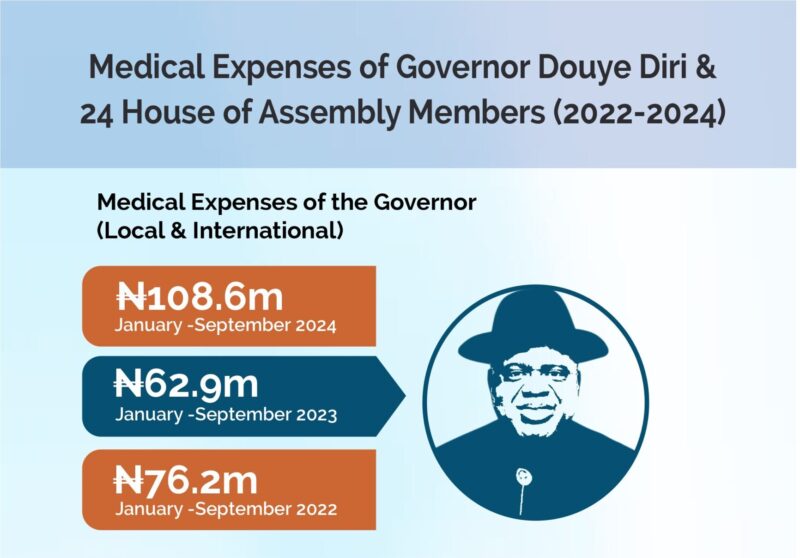

An analysis of the state’s revenue inflows and Budget Implementation Reports over the last three years shows a consistent pattern: while the facilities relied upon by pregnant women in Otuabagi, Bulou-Orua, Gbaran-Ama, Toru-Angiama and other rural communities continue to decay without trained staff, basic equipment or functioning infrastructure, political leaders receive nearly unlimited funding for local and overseas medical treatment.

For instance, in 2022, the only approved project for primary healthcare infrastructure was the rehabilitation of Azikoro PHC and the rehabilitation of other unmentioned health facilities, budgeted at N600.95 million. The state released just N201.5 million for this.

For instance, in 2022, the only approved project for primary healthcare infrastructure was the rehabilitation of Azikoro PHC and the rehabilitation of other unmentioned health facilities, budgeted at N600.95 million. The state released just N201.5 million for this. Yet that same year, the Bayelsa government spent N326.2 million on international and local medical expenses for the governor and the 24 members of the State House of Assembly, an amount 61.8 per cent higher than the total investment in all primary healthcare facilities.

In that same year, however, it disbursed N213.9 million for another international and local medical expenses of the governor and 24 house members.

Across communities visited, residents described the effects of these choices with a mixture of frustration, resignation and grief. Mothers died from bleeding and obstructed labour. Newborns failed to survive their first days of life. Children with fever or seizures were carried long distances because the nearest clinic had no staff or drugs.

Meanwhile, the state’s political elites continued to fly comfortably to foreign hospitals.

Residents repeatedly asked the same question: If the state’s health centres are good enough for the people, why are they never good enough for the leaders?

This reporting was completed with the support of the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID).