All eyes are on the new military regime that replaced the government of former President Andry Rajoelina, who fled Madagascar after several weeks of mass demonstrations. Malagasy are anxious to see whether the junta is a reincarnation of the past – Mr Rajoelina himself took power in a 2009 coup – or if it will deliver on its promises to work with the people to address their problems.

On 25 September, youths describing themselves as Gen-Z took to the streets of the capital Antananarivo and other big cities, protesting against incessant electricity blackouts, water shortages and spiralling corruption. Their demands escalated to include political reforms and Mr Rajoelina’s resignation.

After an initial security crackdown proved ineffective, Mr Rajoelina’s talks with the Gen-Z movement collapsed.

The support and protection of protesters by the powerful Army Corps of Personnel and Administrative and Technical Services (CAPSAT) gendarmerie unit forced the president to flee Madagascar.

On 14 October, parliament voted 130-1 to impeach Mr Rajoelina for ‘abandonment of office.’ The High Constitutional Court upheld the decision and appointed CAPSAT leader Michael Randrianirina as head of state.

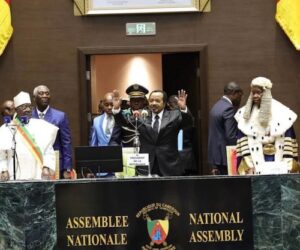

Mr Randrianirina was sworn in as president on 17 October. Despite the court advising him to implement a 60-day transition, he pledged a two-year transition and a constitutional referendum. Meanwhile, the exiled Mr Rajoelina continues to claim the presidency.

The African Union (AU) Peace and Security Council (PSC) responded swiftly to the crisis, suspending Madagascar from all AU activities on 15 October, citing an unconstitutional change of government. The PSC called for a rapid return to constitutional order through an inclusive civilian-led transition and elections. It had already, on 13 October, asked AU Commission Chairperson Mahmoud Youssouf to appoint a special envoy to Madagascar and reactivate the 2011 roadmap.

The AU decision to sanction Madagascar has angered many Malagasy, who see the junta as a legitimate government that came to their rescue.

By contrast, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) opted for a more conciliatory approach. On 14 October, the chair of its Organ on Politics, Defence and Security Cooperation, Malawi’s newly elected President, Peter Mutharika, announced that SADC’s Panel of Elders and Mediation Reference Group would be sent to mediate.

Madagascar’s crisis challenges the AU and regional economic communities’ mutually agreed principles of democratic governance. SADC is in a particularly awkward position because Madagascar – represented by its president – holds the SADC chair until 2026.

The AU’s reactive approach to coups and unconstitutional changes of government reveals its inability to deal with countries facing governance challenges and popular protests. As a result, the AU’s zero-tolerance policy often appears to indirectly protect ousted civilian heads of state even in the face of their blatant constitutional and electoral manipulations.

Gen-Z’s grievances reflect a much deeper malaise. As of 2022, 75 per cent of Madagascar’s 31.9 million people live below the poverty line, while the United Nations Development Programme ranks the country 183rd out of 193 on the Human Development Index 2024.

Graft compounds these hardships. Madagascar ranks 142 out of 180 countries (among the 20 most corrupt in Africa) on Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index. With a gross domestic product of just over $17 billion and a per capita income of $545, Madagascar is one of the world’s poorest countries.

This dismal economic outlook has aggravated Madagascar’s troubled political history. Since independence from France in 1960, political transitions have been punctuated by violence, making the Indian Ocean island vulnerable to insurrections.

The current crisis was initially driven by socio-economic grievances, as happened in movements that arose in Kenya in 2024 and 2025. Madagascar’s youth movement was a powerful mobilising force, but its limited organisational structure left it vulnerable to manipulation by political actors and the military, who have now hijacked the process.

As the country’s recent history shows, there is no guarantee that the transition will deliver a competent and accountable government that provides essential social services.

For the AU, the coup revives the enduring question – already raised during the Arab Spring – of how to address political crises stemming from fundamental governance deficits. The situation also exposes the AU’s early warning deficits and poor communication between its entities.

For example, in August, Mr Youssouf appointed a high representative to Madagascar. Sometime after that, the PSC recommended the closure of some AU liaison offices, including in Madagascar. This type of miscommunication is concerning. Why was the brewing crisis missed by the AU’s Continental Early Warning Mechanism? And what was the capacity of the liaison office to anticipate and exercise preventive diplomacy?

The issue also tests the relationship between the AU and regional economic communities. SADC traditionally tries to limit the AU’s involvement in its subregion, often resulting in different positions on political and security issues. Examples are the 2018 election crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the deployment of SADC troops to northern Mozambique in 2021.

In this case, Mr Mutharika – in his SADC role – pledged unconditional solidarity with the Malagasy people, which could undermine the AU and result in deadlock between the two institutions.

Although outsiders describe recent events as a coup, many Malagasy – including an Antananarivo-based civil society leader who spoke to ISS Today anonymously – see it as a people’s victory in removing Mr Rajoelina. However, they do insist on a return to fresh non-aligned civilian democratic rule.

Madagascar’s protests reveal the growing influence of Gen-Z. Many African countries could face the same, as already experienced in Nigeria, Kenya, and, more recently, Morocco. The civil society leader said many young Malagasy felt the AU reacted only to coups, while ignoring governance issues like the 2023 election boycott and the previous government’s growing authoritarian nature.

The AU and regional blocs have their work cut out for them. They must be better prepared to respond to a future spread of the Gen-Z movement. Many heads of state are aware of this. In 2025, they asked the AU Commission Chair to review the AU Peace and Security Framework to ensure that it adequately addresses contemporary threats.

The AU’s zero tolerance against coups should be matched by a similar attitude towards the type of poor governance that provokes youth protests. Should the AU not adjust, it will continue to grow unpopular to the point where its relevance is questioned.

Martin Ewi, Southern Africa Regional Organised Crime Observatory Coordinator, ENACT, Paul-Simon Handy, Regional Director East Africa and AU Representative, ISS and Zenge Simakoloyi, Research Officer, ISS Addis Ababa

(This article was first published by ISS Today, a Premium Times syndication partner. We have their permission to republish).