In the debt markets, perception can be as damaging as reality. Nigeria, despite being Africa’s largest economy by GDP, continues to borrow at a steep premium compared to its peers. Countries like the Republic of Benin, one-seventh of Nigeria’s economic size, access international markets at lower interest rates and on more favourable terms. South Africa, despite battling its own economic demons, also consistently secures better credit ratings and lower bond yields. This disconnect is not only puzzling but costly. Nigeria pays more to borrow, more to roll over debt, and gets less favourable tenors.

The rating gap and its cost

As of October 2025, Nigeria’s sovereign ratings remain in speculative territory: Fitch rates us B (upgraded from B- in April 2025), Moody’s at B3 (from Caa1 in May), and S&P at B-. By contrast, South Africa sits at BB- (Fitch) and Ba2 (Moody’s)—two to three notches higher. Even Benin commands a B+ rating despite having less than 5% of Nigeria’s GDP and far narrower economic diversification. This seemingly modest differential has profound implications. The gap between B and BB- represents the divide between “highly speculative” and “non-investment grade speculative”, a threshold that determines institutional investor eligibility and risk appetite. In practical terms, Nigeria pays close to 10% on recent Eurobond issuances, while South Africa secures similar-maturity debt at 7-8%. This 200-300 basis point premium translates directly into hundreds of millions of dollars in additional annual debt service costs. Consider the arithmetic: For a $1 billion 10-year issuance, a 250 basis point differential means $25 million in additional annual interest and $250 million in total excess cost over the bond’s life. When scaled across Nigeria’s $42 billion external debt stock, even a 100 basis point premium equates to $420 million in additional annual servicing costs—funds that could finance 840,000 children’s annual primary education or 2,100 primary healthcare centres.

Read also: Borrowing for growth or mortgaging the future? Nigeria’s subnational debt dilemma

The structural realities

To be clear, ratings agencies cite genuine economic vulnerabilities that justify caution. Nigeria’s tax-to-GDP ratio hovers around 6%—among the lowest globally and less than half of South Africa’s 15%. This chronic revenue underperformance creates a dangerous dynamic: petroleum revenues still constitute 50-60% of government income, exposing our fiscal position to commodity volatility, while interest payments consumed 50% of federal government expenditure in H1 2024, crowding out productive spending. The foreign exchange conundrum remains our single largest anchor on creditworthiness. Nigeria imports refined petroleum products despite being Africa’s largest crude producer—an economic paradox that drains reserves. The forex market’s illiquidity and multiple exchange rate windows undermine investor confidence. Investors lending to Nigeria in dollars are acutely aware of the risk that they may not be able to repatriate their profits or principal at a predictable rate. Benin, which uses the CFA franc pegged to the euro, offers investors currency certainty—a commodity more valuable than a few percentage points of yield.

“But economic journalism has a responsibility to inform, not just inflame. A well-structured report on Nigeria’s debt outlook, properly contextualised, can do more to calm markets than a hundred press statements from Abuja.”

Macroeconomic instability compounds these challenges. Year-on-year inflation above 20% throughout 2023-2024 necessitated the CBN maintaining benchmark rates at 27%, among the world’s highest. Projected GDP growth of 3.3-3.6% barely exceeds population growth, limiting per capita income gains. With debt-to-GDP approaching 50% (including contingent liabilities and state/local debt), trajectory concerns persist.

Read also: Reps approve Tinubu’s plan to borrow $2.35bn, issue $500m sovereign sukuk

Yet these fundamentals explain perhaps only 60-70% of the rating differential with South Africa. The remainder lies in perception dynamics.

The amplification effect: When media becomes a risk multiplier

Credit rating agencies explicitly incorporate “governance perception” and “institutional credibility” into sovereign assessments. Here, Nigeria faces a paradoxical challenge: the very media freedom and civil society activism that should signal democratic health instead often amplifies every misstep, creating a narrative of perpetual crisis. Consider two recent reform examples. The Tinubu administration’s June 2023 decision to eliminate petroleum subsidies—long advocated by the IMF and World Bank as essential reform—generated months of intense criticism. International media coverage focused almost exclusively on protests, hardship, and implementation challenges. Underreported were the economic imperatives: subsidies had reached ₦4.4 trillion annually (2.3% of GDP), with 70% of benefits accruing to the top income quintile. During peak criticism (July-September 2023), Nigeria’s Eurobond spreads widened by 180 basis points relative to the African sovereign index, despite the reform being fundamentally credit-positive. Investor surveys revealed media narrative as the primary concern, not underlying policy.

Similarly, the CBN’s exchange rate unification was portrayed primarily through the lens of naira depreciation (from ₦460 to ₦750+). Headlines emphasised “Naira crashes to record low” and “Economic crisis deepens.” What received less attention: elimination of ₦7.3 trillion in annual arbitrage losses, a tenfold increase in daily forex market turnover (from $40 million to $400 million+), and attraction of over $5 billion in previously withheld foreign investment. Rating agencies noted the reforms positively in technical assessments but cited “implementation risks amplified by public concerns” as limiting upgrade momentum. The perception lag cost Nigeria 6-9 months of credit improvement. This is not unique to Nigeria. However, the comparative media environment reveals stark differences. South African media, despite facing severe challenges (electricity crisis, 30% unemployment, state capture scandals), tends toward technical economic analysis. Headlines read “Treasury announces fiscal consolidation plan” rather than “Government to slash spending.” This framing—clinical rather than catastrophic—moderates investor panic.

Nigeria’s vibrant but often sensationalist media ecosystem operates on attention economy principles. A ₦50 billion ($60 million) procurement controversy receives weeks of front-page coverage, while ₦12 trillion ($14 billion) in infrastructure delivery passes with minimal notice. The psychological impact on investors cannot be overstated. Portfolio managers in London or New York—allocating billions based on partial information—rely heavily on media sentiment analysis. When every Nigerian economic data release is framed as a crisis or scandal, even positive developments get discounted.

The Digital Age risk premium

Rating agencies now explicitly monitor social media sentiment as a leading indicator of political and social stability risk. Nigeria’s massive digital population (150+ million internet users) creates unique challenges in volume, velocity, and verification. Nigeria generates 3-5x more social media content per capita than Benin, creating more data points for negative sentiment capture. Controversies escalate within hours, as the #EndSARS protests of 2020 demonstrated—initially a legitimate grievance about police brutality morphed via social media into a perceived governance crisis, with international media picking up user-generated content uncritically. False narratives about inflation figures, debt levels, and policy decisions circulate widely before corrections gain traction. By then, damage to investor perception is done. International financial institutions now apply what they privately term a “Nigeria noise premium”—typically 50-75 basis points—to account for the likelihood that any investment will face unpredictable social media-fuelled controversy.

Read also: State of States 2025: Anambra top states able to cover its expenditure without borrowing

Lessons from Benin’s quiet competence

Benin’s superior rating offers instructive lessons. Beyond its WAEMU membership and CFA franc peg, which eliminates exchange rate risk, Benin benefits from policy consistency and limited international media attention. Negative incidents don’t compound into sustained narratives. Benin doesn’t promise transformation, so it doesn’t disappoint; Nigeria’s potential creates higher expectations and greater disappointment when unrealised. The lesson: quiet competence sometimes outperforms dramatic ambition in capital markets.

The cost of perception

Nigeria’s challenge is not size but signalling. The country struggles to project a coherent economic narrative. Repeated FX policy reversals, weak fiscal buffers, and political inertia send conflicting signals to global investors. Each policy whiplash leaves a dent in investor confidence. Markets reward clarity, not size—which is why a small but predictable country like Benin gets a better deal. Nigeria’s excess borrowing cost, the premium paid above what fundamentals alone would justify, amounts to approximately $300-400 million annually. Over a decade, this is $3-4 billion. We are, in essence, paying a “perception tax”—financing the gap between our economic reality and our projected image. This is not a call for censorship. But economic journalism has a responsibility to inform, not just inflame. A well-structured report on Nigeria’s debt outlook, properly contextualised, can do more to calm markets than a hundred press statements from Abuja.

Rebuilding credibility

What Nigeria needs is not just capital, but credibility. The current administration has shown flickers of fiscal courage, from subsidy removal to FX unification. But reforms half-done or rapidly reversed hurt more than help. Markets don’t punish weakness—they punish indecision. If Nigeria is to pay less for debt, it must reduce the uncertainty premium attached to its name through stabilising policies, clarifying fiscal rules, and professionalising public communication. The rating agencies are not wrong to exercise caution. Our structural vulnerabilities are real and require sustained reform effort. But they are also not seeing the full picture. Nigeria’s vibrant democracy, free press, and engaged civil society—features that should signal resilience—are instead misread as indicators of instability. Every basis point of borrowing cost reduction translates to millions in savings for productive investment. Capital is global, but trust is earned. Nigeria must now do the hard work of rebuilding it. The premium of perception is too expensive to ignore.

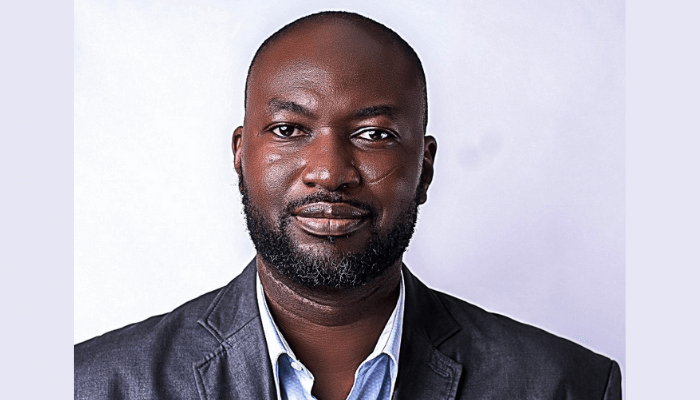

Dr Oluyemi Adeosun, Chief Economist, BusinessDay.