As a Nigerian woman, I often hear stories about “family curses”, the ones whispered at gatherings when an aunt is newly widowed or when someone’s daughter turns thirty-five without a husband in sight.

In these stories, the tragedy is almost always marital, with women who never marry, women who die once they do, women whose husbands die, or women who lose children or struggle to birth them.

It’s always some affliction tied to love, tied to men, tied to marriage, as if womanhood itself is a battlefield where affection becomes collateral damage.

So, going into Cursed Daughters, the core theme wasn’t new to me. What I didn’t expect was how deeply unsettling it would feel to witness these patterns play out through the Falodun women, a family so eerily familiar that I felt like I knew them.

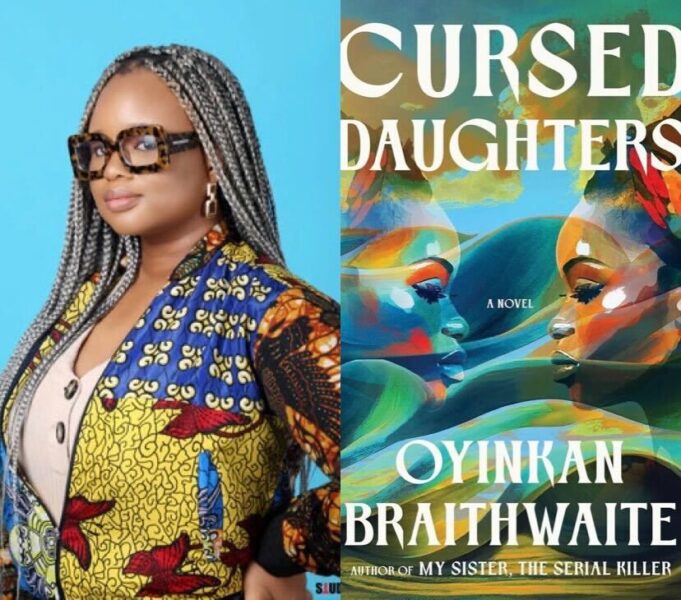

Oyinkan Braithwaite, the Nigerian-British author best known for My Sister, the Serial Killer, steps into new territory with this novel.

In an interview with the Chicago Review of Books, she admitted she could have written a sequel to her bestseller but chose instead to challenge herself. “I wanted to try to do things I had never done before in my journey as a writer,” she said. That she did, because Cursed Daughters feels more mature and more intimate.

A Story That Begins at an Ending

The novel opens at Monife’s burial. Ebun, heavily pregnant and emotionally frayed, returns home from the funeral only to discover that Aunty Bunmi has already wiped away all traces of Mo: her photos, her things, her presence. When Ebun confronts her aunt, her water breaks suddenly, and she goes into premature labour.

Her daughter arrives safely, and almost immediately, the supernatural undertones creep in. Ebun dreams of Monife holding her newborn, and she wakes up violently. Aunty Bunmi, late Monife’s mother, hints at calling Mama G (the mamalawo) if things get stranger. And things do get stranger.

How It All Began: The Day Mo Entered the House

The narrative pulls us back into Ebun’s childhood: a lonely, muted existence in the large Falodun house where her mother, Kemi, was mostly absent, leaving her with chores and silence. Ebun was a painfully shy child with no friends and no imagination to compensate for the solitude.

Everything changed the day Aunty Bunmi arrived from England with her two daughters: Tolu, the standoffish teenager, and Monife, the warm, curious fifteen-year-old who found Ebun in all her hiding spots and pulled her into life.

Mo became Ebun’s compass. Her joy. Her first friend. But Mo was unpredictable, as she was deeply loving one day and withdrawn and unreachable the next. Her bouts of sadness cast shadows over the entire house, but whenever she resurfaced, she returned with sunlit affection. She is the one who told Ebun about the Falodun curse.

READ ALSO: If Heartbreak Had a Soundtrack, It’d Be A Broken People’s Playlist

The Origin of the Falodun Curse

The novel rewinds further, tracing the lineage to Feranmi Falodun, whose beauty attracted a travelling stranger. After she seduced him, her family insisted on a full bride price, turning what he saw as a spiritual encounter into a forced union.

Feranmi bore him twins, only to discover he already had a wife. When the two women clashed physically, the first wife laid a devastating curse:

“It will not be well with you. No man will call your house a home… Your descendants will suffer for man’s sake. Ko ni da fun e,” she promised.

This curse sets the stage for a cycle of broken engagements, unhappy marriages, and tragic losses that plague the Falodun women for generations.

Monife’s heartbreak is central to the story’s emotional core and shows the curse’s brutal effect.

Despite her relationship with the “golden boy,” Kalu, his mother rejected her because of the Falodun curse. Desperate, Mo visited a spiritual practitioner who instructed her to bind him through blood:

“These kinds of unbreakable bonds… they always require blood.”

The ritual involved writing his name, placing it in her menstrual pad, and drinking a sandy concoction, a disturbing, painful depiction of how far women go to be loved when they’ve been told love will never stay.

Kalu eventually married someone else but continued his affair with Monife. She became pregnant, and so did his wife, Ada. Monife lost her baby, lost Kalu, and ultimately lost herself. She walked into a river and didn’t return. Her death is the ghost that haunts the novel.

READ ALSO: What “Only Big Bum Bum Matters Tomorrow” Says About The Battle for Approval

A Reincarnated Shadow: Eniiyi

Back in the present, Ebun names her daughter Eniiyioluwa, but Aunty Bunmi insists the child is Monife returned and names her Motitunde, which means “I have come back again.”

As she grows, Eniiyi resembles Mo frighteningly: the full hair, the mannerisms, the artistic references to “big her and little her.”

Ebun refuses to believe her daughter is Mo reborn, but the novel makes it clear that the past is not finished with this family.

The Curse Returns in a New Generation

When Eniiyi falls for Zubby, her mother rejects him immediately, and only later do we learn why. Zubby is Kalu’s son. The same Kalu who destroyed Monife, and it’s evident that it is the curse looping back.

But Eniiyi refuses to follow her foremothers into ruin. She ends the relationship before it ends her. She decides the curse stops with her, even if her heart aches for what could have been.

My Takeaways

As a Yoruba woman from an extended family myself, reading Cursed Daughters was surprisingly nerve-wracking. The Falodun household, full of aunties, children, secrets, and that big ancestral house built “just in case”, felt too familiar. The idea that a man didn’t believe in curses yet built a six-daughter fallback home? Very Nigerian. Very Yoruba. Very real.

I was also struck by the religious duality of how a devoutly Christian family could so casually consult mamalawos when it came to marriage, childbirth, or destiny. This mix of Christianity and traditional belief is common in many Nigerian households but rarely depicted honestly in fiction.

Reincarnation, also called ‘Àtúnwáyé’ or ‘Ìpadàwáyé’, is another thread woven delicately into the novel.