2

ABUJA – The first light of dawn washed Abuja in a pale orange haze as I packed my bag for Maiduguri—a city whose name had, for more than a decade, been synonymous with terror, displacement, and defiance. To travel there today was not just a trip across Nigeria’s northern highways, it was a quiet pilgrimage through the geography of resilience.

Leaving Abuja before sunrise, the highway stretched like a long, uncertain sentence—each kilometer punctuated by the memory of news headlines that once carried words like ambush, checkpoint attack, IDP camp, and suicide bomber. Yet, for every haunting recollection, there was also the hum of possibility. Petrol stations along the way were busy, food sellers arranged their wares, and the faint optimism of a normal day whispered through the morning air.

Past Kaduna, the journey assumed its Northern texture. The sky widened; trees grew sparse and low; the Sahelian dust began to rise in soft swirls. Between Zaria and Potiskum, the security presence thickened—armoured personnel carriers, sand-bagged checkpoints, soldiers peering from helmets. It was an uneasy reassurance: protection and reminder rolled into one. At each stop, passengers descended to stretch, joke, or offer silent prayers. One young man from Gombe, travelling to see his parents for the first time in three years, told me quietly, “Things are calmer now. Before, we only heard explosions. Today, we hear generators and markets again.”

The words stayed with me.

Between Damaturu and Benisheikh, the security intensity deepened. Soldiers waved down every vehicle, their rifles slung with practised ease. The officer at one checkpoint, sweat trickling down his temple, inspected our IDs and said almost casually, “The road is safe, but stay alert. We’ve worked hard for this calm.”

I asked if he missed home. He smiled, tiredly. “This is home now. The war may be quiet, but it’s not over. We’re just making sure peace learns to walk again.”

Those words—making sure peace learns to walk again—summed up the new Borno. It is a fragile peace, one guarded by weary soldiers and determined civilians.

By late afternoon, the road opened into the familiar city that had dominated Nigeria’s counter-insurgency headlines for years. Maiduguri was calm—too calm, perhaps, for a place that had endured so much. The wide roads were surprisingly clean, lined with neem trees and the low murmur of commerce. Motorcycles buzzed again, keke NAPEPs ferried commuters, and children in neat uniforms trotted home from school.

At the city gate, the signboard Welcome to Maiduguri Metropolitan Council stood like a quiet badge of honour. The driver muttered, “This city no dey fall.” He was right. Maiduguri never fell, not even in its darkest nights.

Monday Market, once burned and bombed, now throbs with new life. Women balanced baskets of tomatoes, men shouted prices over sacks of millet and beans, and the smell of fried groundnuts mingled with the sharp scent of petrol fumes. Near the rebuilt stalls, a young trader named Bakura offered me a cold sachet water. I sat, watching hundreds of bicycles parked near the market by traders.

“We are starting small again,” he said. “Before, everything scatter. Now, customers are coming from villages that were empty before. We still fear sometimes, but hunger is stronger than fear.”

Across the street, two women from Konduga sold colourful fabrics beneath a patched umbrella. One of them, Falmata, told me she had lost her husband in 2015. “For three years I was in Muna IDP camp. When I came back, I started this business with five thousand naira. Every day, I thank Allah that I can feed my children.”

It struck me how every sentence in Maiduguri seemed to carry both loss and survival in equal measure.

At dusk, the call to prayer rolled over the city. The muezzin’s voice felt like a lullaby to a wounded place. Not far from the mosque, the walls of the University of Maiduguri still bear faint scars of past explosions. Yet students thronged the gates—laughing, debating, clutching notebooks. A lecturer told me enrollment had grown again. “Education is our victory,” he said. “When the classrooms are full, Boko Haram has lost.”

Night in Maiduguri is not what outsiders imagine. The curfew still exists in pockets, but small restaurants stay open late. I ate rice and suya at a roadside joint where soldiers, journalists, and aid workers mixed easily. A group of students teased one another about generator noise drowning their phone calls. Life, it seems, refuses to stay silent.

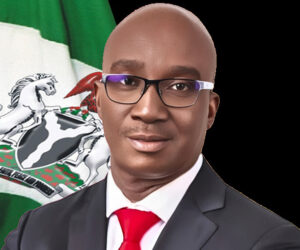

Governor Zulum’s Imprint

It is impossible to journey through today’s Borno without noticing the administrative energy of Governor Babagana Zulum. His picture is everywhere—not out of vanity, but as shorthand for a new social contract. Residents speak of him with a blend of affection and awe.

At the newly opened flyover near the Post Office Roundabout, a commercial driver said, “Zulum is our stubborn father. He goes everywhere. Even soldiers respect him.”

Indeed, the governor’s approach— combining fearlessness with welfare delivery—has become the backbone of Borno’s gradual healing. Schools rebuilt, markets reopened, thousands resettled. Yet even he admits the task is incomplete. The ghosts of insurgency still hover on the state’s peripheries.

I visited the outskirts where some internally displaced persons still live in transition shelters. Children chased each other in the sand, their laughter filling spaces once occupied by despair. In a small hut, I met Aisha, a widow from Bama, who now runs a micro-loan cooperative for 20 women. “They told us to wait for help,” she said, “but we decided to help ourselves. Each week, we contribute one thousand naira and buy goats. That’s our new life.”

Nearby, aid workers from an international NGO distributed solar lamps and food packs. A volunteer whispered, “The big challenge now isn’t just hunger—it’s rebuilding trust. Many people still fear returning home. But every returnee brings a little more confidence to others.” In the heart of the city stands the Shehu of Borno’s palace—an ancient seat that has witnessed empires, jihad, colonialism, and now insurgency. The Shehu’s court remains a place of counsel and calm. Traditional institutions, once dismissed as relics, now play vital roles in reconciliation and community surveillance.

At a Friday prayer, I watched men and women pour into mosques under the blazing sun, their shadows merging on the sandy ground. For them, faith is not just religion; it is resilience. The sermons focus on forgiveness, tolerance, and rebuilding community life. One imam said in Hausa, “Peace is like water; if you don’t fetch it daily, it dries.”

Education: The New Frontline

Across town, a newly refurbished school compound buzzed with students reciting English alphabets. The headmistress, Mrs. Yagana Modu, showed me classrooms built from the ruins of a previous attack. “These children were born in IDP camps,” she said. “Now they want to be teachers, doctors, journalists. That’s the real victory.”

The state government’s partnership with donor agencies has helped rebuild over 500 classrooms since 2019. Yet the greater achievement is psychological—convincing families that school is safer than silence.

Perhaps nothing captures the city’s transformation better than its evenings. As the heat softens, people gather at tea stalls known as maishayi joints. Men sip sugary tea, debating politics; young women in hijabs scroll through TikTok; soldiers in mufti share jokes with bus drivers. In these casual scenes, the extraordinary becomes ordinary again.

At one stall, a young man named Abba Yusuf, once displaced from Gwoza, now studies computer science. “When I first came here,” he said, “I slept under a tree. Now, I design websites for small businesses. Life can start again if you refuse to stop dreaming.”

To outsiders, Maiduguri may still evoke images of destruction. But to those who live here, the narrative has shifted from tragedy to tenacity. Roads once feared are now busy again. The hum of generators replaces the sound of explosions. Markets pulse with commerce; classrooms with laughter.

Yes, there are still attacks in remote villages. Yes, the scars remain. But within the city walls, there’s a collective vow never to return to the darkness.

On the return trip, the checkpoints felt less intimidating, the horizon less heavy. The sun, dropping low over the plains, cast a soft golden light that made even the warscarred landscape seem forgiving.

At a roadside canteen near Damaturu, a soldier eating beans beside me said, “People think we’re fighting only Boko Haram. We’re also fighting hopelessness. When people believe again, our job gets easier.”

Back in Abuja the next evening, the city lights looked different— cleaner, almost innocent. I realized that Maiduguri had not only survived; it had taught me something profound about Nigeria itself: that a nation, like a person, can walk through fire and still emerge with its soul intact.

The journey to Maiduguri is no longer an expedition into fear; it is a window into Nigeria’s slow but steady recovery. The North East remains scarred, yet its people are rebuilding from beneath the ashes. Their courage is quiet but unmistakable—the teacher reopening a classroom, the trader restarting her stall, the farmer returning to a reclaimed field.

For a region once reduced to headlines of horror, Maiduguri today offers a different story: of hope under the desert sun, of women and men reclaiming dignity, of peace learning, indeed, to walk again.