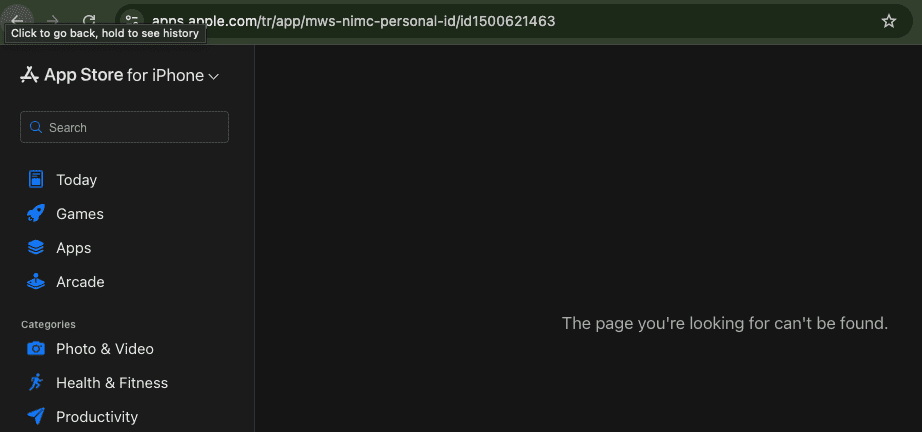

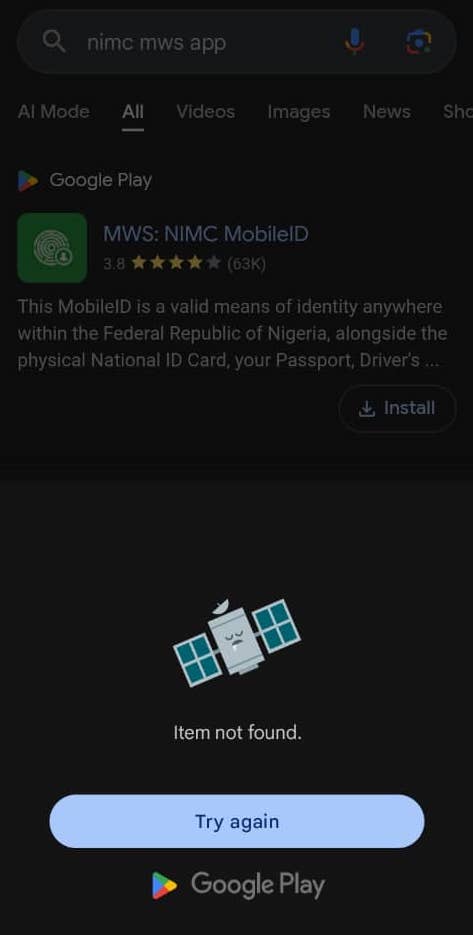

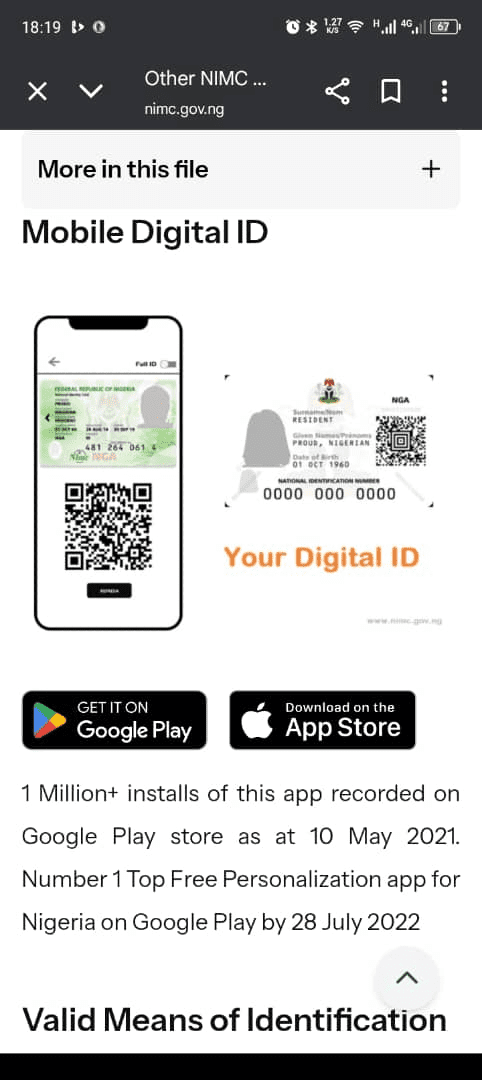

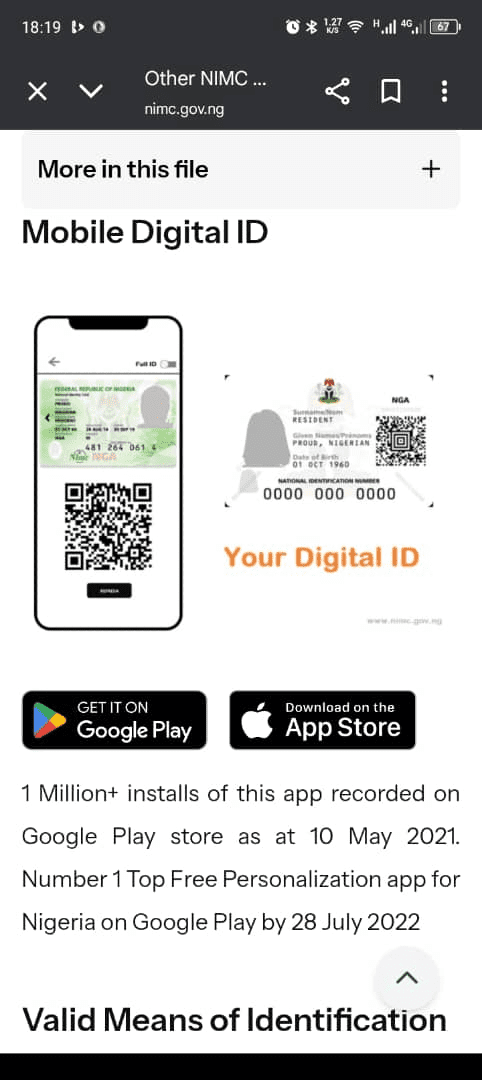

Nigeria’s national ID verification system has quietly transformed, and the government hasn’t bothered to explain what’s happening. The NIMC Mobile Web Service portal, which banks, telecoms, and fintech companies have relied on for years to verify customers’ identities, is currently inaccessible. The agency’s mobile app has disappeared from both the Google Play Store and the Apple App Store. And there’s been no official communication about any of this.

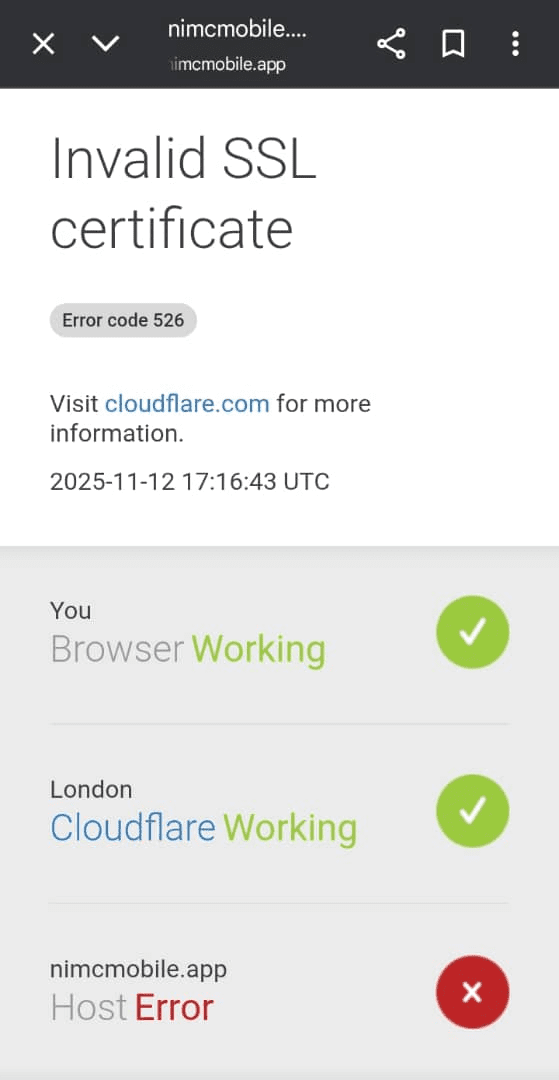

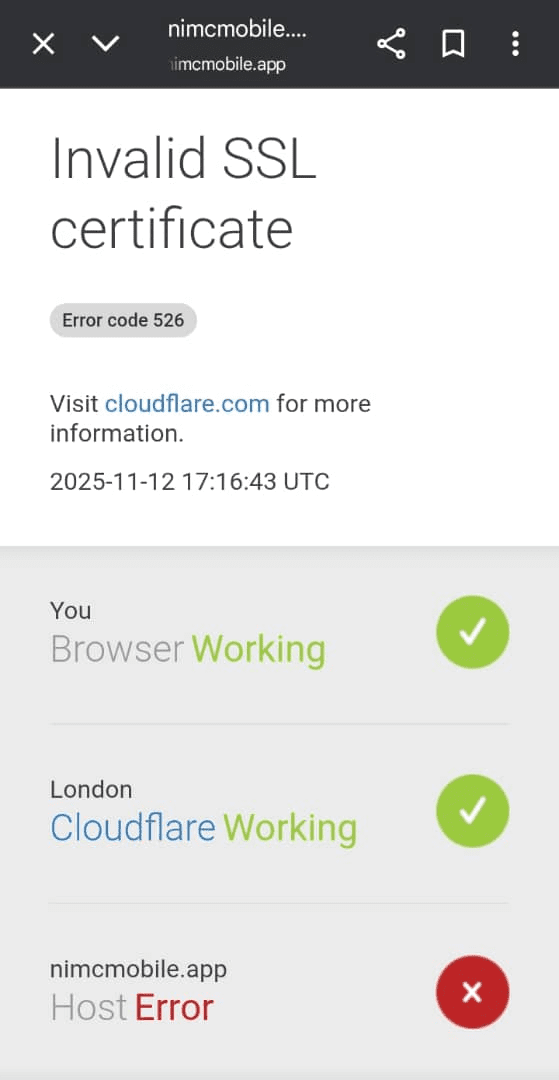

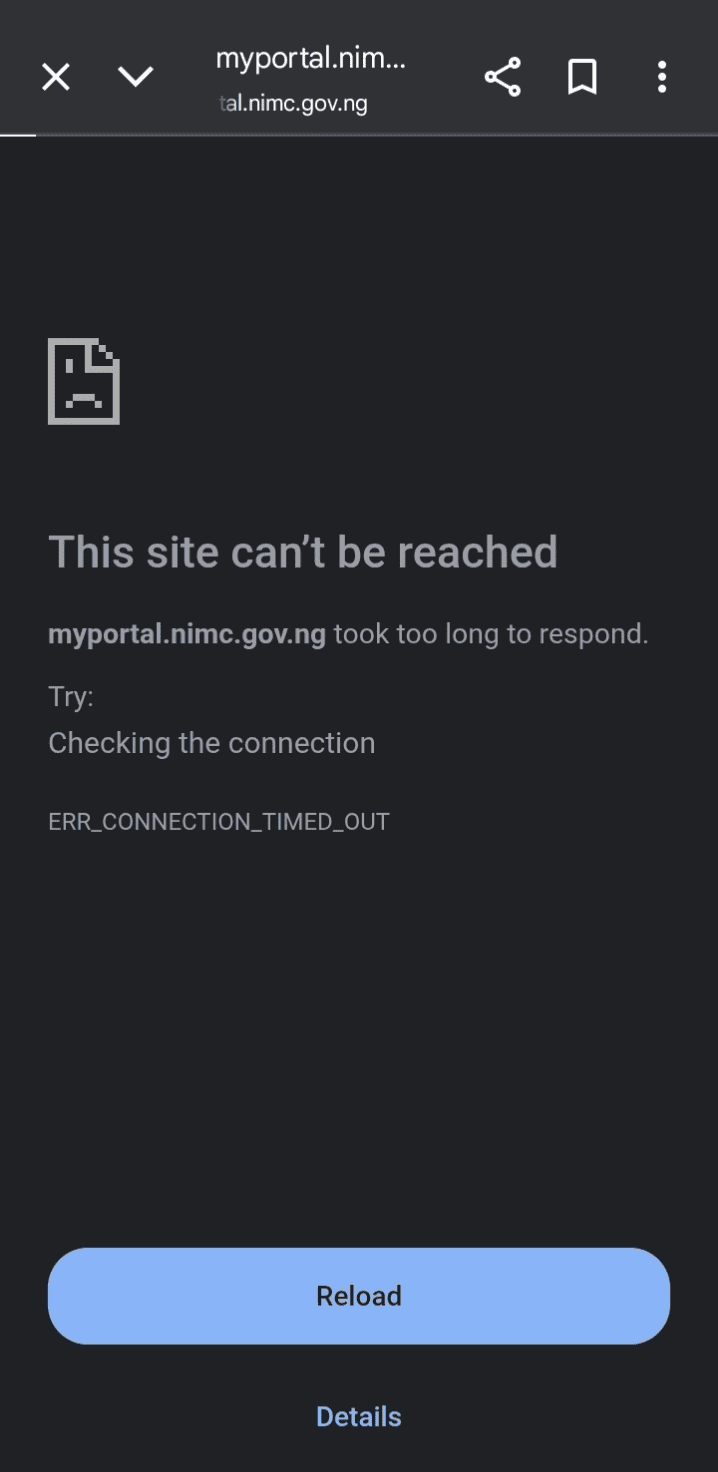

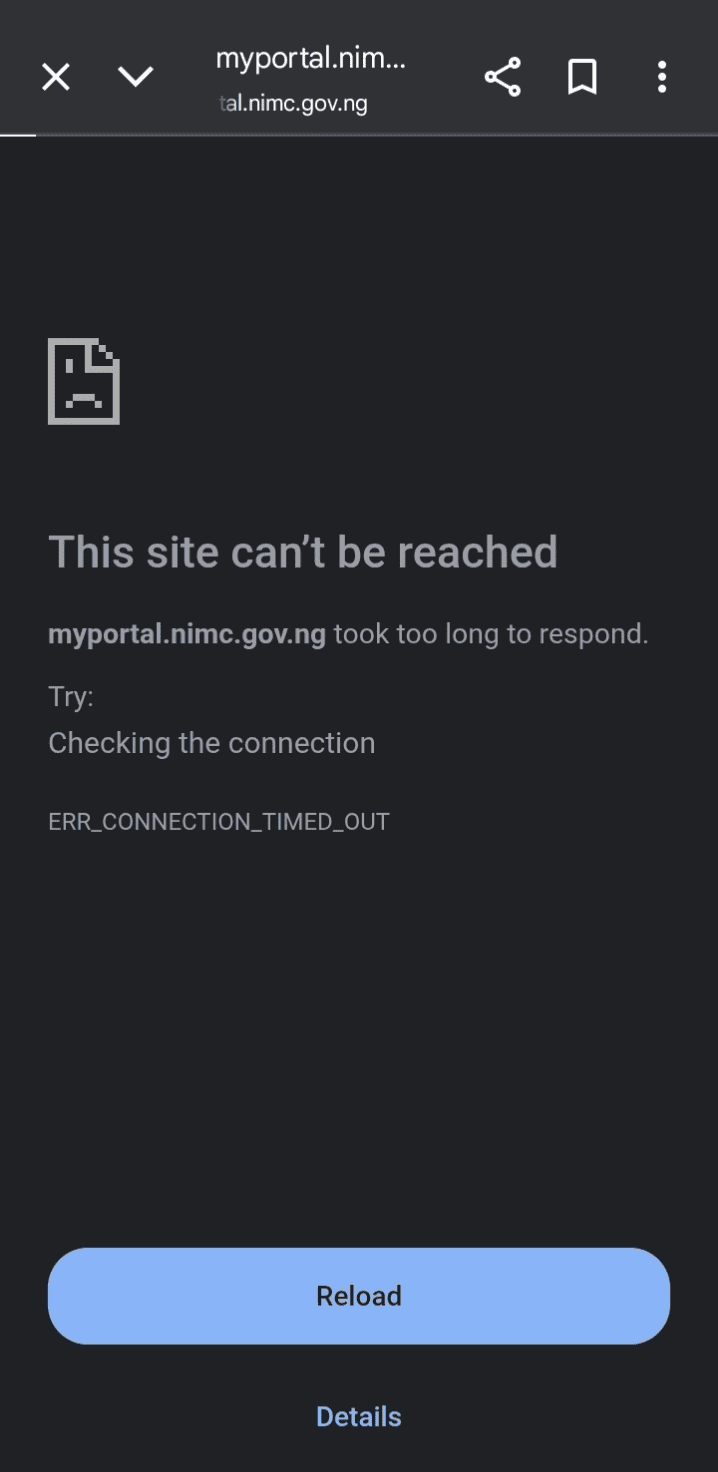

Technext confirmed on multiple occasions that the MWS portal at mws.nimc.gov.ng returns error messages when accessed. Searches on both major app stores show the previous NIMC app is no longer available for download. As of the time of publication, these services remain unavailable, and the National Identity Management Commission has made no public statement explaining the changes.

What we know about ID verification

The timing coincides with the recent launch of NINAuth, a new digital verification platform unveiled by President Bola Tinubu at the State House in Abuja.

NINAuth offers tokenised authentication, digital ID display, and facial matching technology. It’s positioned as a modern, secure way for citizens and institutions to verify identities without exposing personal NIN data.

The platform integrates directly with Nigeria’s National Identity Database and allows government agencies and private companies to authenticate identities through what NIMC describes as a more secure framework. The technology appears aligned with global digital identity standards, emphasising data protection and interoperability.

On paper, this sounds like progress. In practice, the transition has been opaque and potentially disruptive.

What we don’t know

Critical questions remain unanswered. When exactly did the MWS portal go offline? NIMC hasn’t said. Is this a temporary technical issue or a permanent decommissioning? No announcement has been made. Has the old mobile app been officially retired, or is its absence from app stores an error? There’s been no clarification.

More importantly, what happens to the hundreds of institutions that built their verification systems around MWS infrastructure? Banks use NIN verification for Know Your Customer compliance. Telecoms rely on it for SIM registration. Fintech companies integrate it into their onboarding processes. These aren’t small players experimenting with new tech, they’re essential services that millions of Nigerians use daily.

For these institutions, a new platform means new integration requirements, new APIs to learn, new developer documentation to study, and new migration timelines to plan. None of this information appears to be publicly available. NIMC’s channels have provided no guidance on how organisations should transition from MWS to NINAuth, or whether they’re expected to at all.

Why silence is unacceptable

For a system as foundational as national identity management, this communication gap creates real problems. Digital infrastructure depends on predictability. Organisations need lead time to adapt their systems. Users need to understand how to access services. When changes happen without warning or explanation, the result is confusion at best and operational disruption at worst.

This isn’t how serious countries handle critical infrastructure transitions. When India modernised its Aadhaar system, the government provided phased announcements and clear migration guides. Kenya’s Huduma Namba rollout included public communication about timelines and changes. These weren’t perfect processes, but they recognised a basic principle: when you’re changing systems that affect millions of people and thousands of institutions, you tell them what’s happening.

Nigeria’s approach suggests either poor coordination or a troubling disregard for transparency. Neither reflects well on the institutions responsible for managing the country’s digital identity infrastructure.

There’s another concern worth considering. The MWS portal was web-based, allowing relatively open integration for third-party services. NINAuth appears to be app-centric, requiring explicit registration and authorisation through NIMC’s backend. This gives the Commission tighter control over who accesses the system and how.

Control isn’t inherently bad, as better security and reduced fraud risk are legitimate goals. But an app-based model also creates potential barriers. Smaller organisations without significant technical resources might struggle with integration. Individuals in areas with limited smartphone access could find themselves locked out of verification services they previously accessed through web portals.

If NINAuth is now the primary, or only, channel for identity verification, its design and accessibility will determine whether this transition represents progress or another form of digital exclusion.

What should happen now?

NIMC owes Nigerians clarity. If MWS has been replaced by NINAuth, that decision should be publicly announced with a clear explanation of why the change was made and what benefits it provides. If there’s a technical issue affecting MWS, the timeline for resolution should be communicated immediately. If the old mobile app has been decommissioned, users who downloaded it need guidance on the next steps.

Organisations that depend on identity verification services need migration documentation, developer access to NINAuth’s APIs, and realistic timelines for transitioning their systems. These aren’t unreasonable demands—they’re basic requirements for managing critical infrastructure responsibly.

Beyond the technical details, there’s a broader principle at stake. Government digital services are not products that can be swapped out silently in the night. They’re public infrastructure that citizens and businesses depend on. Managing them requires not just technical competence but institutional transparency and accountability.

Right now, Nigeria’s national identity system exists in a state of unexplained transition. Whether this represents technological progress or bureaucratic dysfunction depends largely on information NIMC has chosen not to share. That silence, more than any technical decision, is what demands attention and explanation.