Africa can no longer depend on aid or external capital to finance its growth, four central bank governors said, arguing that the future of the continent’s financial system must be built on its own savings, institutions, and innovation.

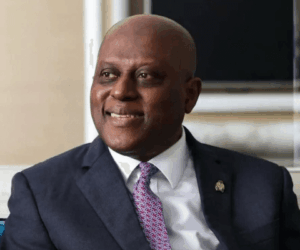

“Banks, for their part, must do more to mobilise resources,” Jean-Claude Kassi Brou, Governor of the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO), said during the closing panel of the Africa Financial Summit in Casablanca on Tuesday. “We will review regulations, if necessary, but the first move must come from the banks themselves. Too often, they rely on deposits from governments and large corporations. They must be more imaginative, especially in tapping long-term resources such as insurance funds, pension funds, and diaspora bonds.”

It was a challenge aimed squarely at the continent’s banking system, which remains heavily dependent on short-term deposits. Kassi Brou’s call for “imagination” reflected a broader argument that Africa’s financial strength lies not in new aid packages but in unlocking the wealth already circulating within its borders.

According to World Bank data, gross domestic savings in Sub-Saharan Africa have trended at roughly 16 % of GDP. By comparison, many Asian peers enjoy savings rates well above 30%. With lower domestic savings, the pool of capital available for investment is smaller.

Meanwhile, bank assets across the region, as a share of GDP, averaged about 41.5% in 2021. That suggests banks are active, but not necessarily channeling savings into long-term investment. The question raised by the governors: are these assets working for development, or still parked in short-term government or large-corporate deposits?

Digitalisation as the next frontier of financial supervision

For Manuel Antonio Tiago Dias, Governor of the Banco Nacional de Angola, the path forward will be shaped by technology. “We know that digitalisation will be central to expanding financial inclusion,” he said. “The central bank itself is looking to integrate AI into its work: in supervision, reporting, and risk analysis. Commercial banks will not wait for us to act first, so we must evolve together.”

His remarks underscored a growing reality among African regulators that technology is no longer peripheral to finance but embedded in its infrastructure. In Angola, the central bank has automated its monitoring processes with AI tools and is finalising a cybersecurity regulatory framework for financial institutions. Kenya’s Central Bank has licenced 153 digital credit providers and is developing a Fast Payment System that will allow instant transactions across all financial institutions, including banks and payment service providers (PSPs). Nigeria’s Central Bank is expected to roll out open banking “soon.”

André Wameso, Governor of the Central Bank of the Congo, offered a reminder that digital transformation is also a development shortcut. “We must embrace the world as it is — one driven by digitalisation,” he said. “In countries like ours, industrial infrastructure is scarce, but new technologies can help us leapfrog traditional development paths. Thanks to systems like Starlink, we no longer need to wait two or three centuries to build fiber-optic networks.”

Michael Atingi-Ego, Governor of the Bank of Uganda, pointed to another challenge: the imbalance in credit allocation. “Governments are increasingly crowding out the private sector in credit markets,” he said. “We must be innovative. One path forward is to institutionalise Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) principles within our financial systems. By embedding environmental, social, and governance criteria, we can encourage banks to channel more credit into agriculture and to support local content.”