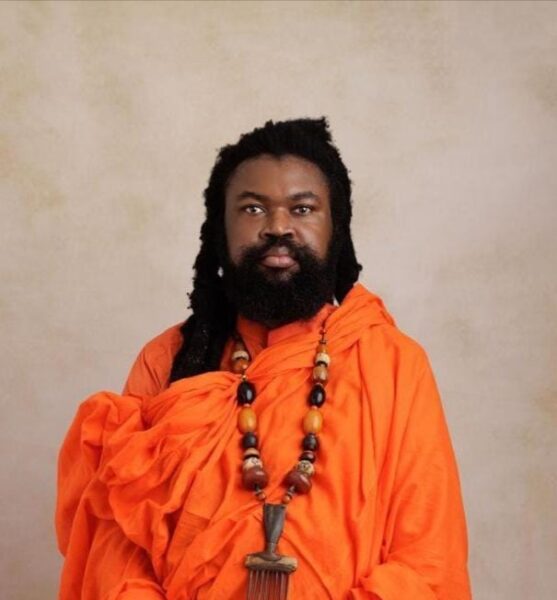

Onyeka Nwelue, an internationally-acclaimed writer, discusses his writing, inspirations and life with AWAAL GATA

What sparked your passion for writing, and how did you know it was what you wanted to do with your life?

I was introduced to creative ideas and thinking at a very young age. I already knew what I wanted to do with my life at 9. However, I was surrounded by people who read Law. As I grew up, they kept trying to get me to read Law and become a church priest. Otherwise, I knew I wanted to be a visual artist, a musician and a writer.

Your novel “The Nigerian Mafia Mumbai” explores themes of violence, drugs, and human trafficking. What drew you to these topics, and how did you approach researching and writing about them?

I travel a lot and people wonder why. I felt something within me needed to write mostly about travellers. In the midst of all that, I listen to conversations a lot and also build up characters in my head. People around me inspire me and newspaper captions too. I see a lot of people getting busted for carrying cocaine at the airports and I never see them in real life but only on front pages of newspapers. A lot of inspirations come from newspapers.

You have spoken about the influence of Wole Soyinka on your writing career. What specific lessons or values did you take away from his mentorship, and how have they shaped your approach to writing?

I still do. Wole Soyinka is an ocean of ideas and knowledge. A stream that never dries as we say in Igbo, ‘osimmiri ataata’. Every moment spent with him is a new opportunity and a chance to learn something new. What people who have never come up close to him, don’t know, is that any moment spent with him, is a class. A masterclass. He is not only brilliant, but the best company to hang around. Then, he has written more than 100 books. What is Guinness Book of Records doing?

I wouldn’t want to go on, before the witches say this conversation with you is a smokescreen. There are some demented people who always say that. This is a man I have loved from my teenage years and I haven’t found any flaw in him.

As a prolific writer, how do you balance your creative work with your academic and other pursuits? Do you have any tips for aspiring writers on managing multiple passions and responsibilities?

It is important to have a lot of money, so you can do whatever you want. People have questioned my source of income. I have been attacked for that. My circle of friends will tell you I am the one who bugs them a lot; who is always asking for money. They also understand that I do a dignifying job: writing and filmmaking. These things need money.

I am not sure I should say this here, but there was a time my health failed me badly, and Professor Wole Soyinka wired me money to focus on my health. That gave me time to also think and write and not worry about my medications.

My health is fragile. So, I spend more time at home, thinking and writing. I am always creating outlines of new books. This is not a life for everyone so it is not for everyone.

Your writing often explores themes of identity, culture, and social justice. What role do you see literature playing in shaping our understanding of these issues, and how do you hope your work contributes to these conversations?

I am currently teaching at a university far away in North America. One of my aunts told me today that low profile is her default setting. Stemming from my experience at Oxford and Cambridge, I will not mention the name of this prestigious university – mostly for my sake. The lessons that I teach there are based on Africa.

Your novel “The Abyssinian Boy” was published when you were just 21. What was it like to achieve such early success, and how did it shape your approach to writing and your career aspirations?

Young people come up to me and want me to help make their journey in life easy. I laugh. Starting early in life is very important. I even tell my younger brothers. These days, everyone in our generation is confused. They just don’t get it. The public gyms are full of them. They are confused. They don’t know what to do with their lives. They say they are gym instructors. In their heads, they think they are now doctors and can prescribe medicines for them. At the same time, they think they are traders. A lot of things going on, because they didn’t start early in life. They are not sure what to do any more. So, they go to the gym so it will look like they are not jobless. Where I stand, they are jobless and they don’t know what to do at all.

You’ve written about your experiences travelling and living in different countries, including India and Rwanda. How have these experiences shaped your perspective on identity, culture, and belonging, and how do they inform your writing?

Currently, one country I am obsessed with is Japan. I have even written a book called “Think Like a Japanese” and another one called “A Japanese Professor in Accra”, which Chief Dele Momodu recently posted pictures of himself handing over to the President of Ghana, Dr. Dramani Mahama.

I visit countries to study them and understand their history and ethos. So, that is what I do with all these travels. I have written extensively about India.

I have a book on Rwanda. It is not a nice book. It was inspired by my experience there. I was in prison in Rwanda, for tweeting at the President.

As a writer and academic, what advice would you give to young Nigerians who are interested in pursuing careers in the arts or humanities?

No advice.

What is next for you? Do you have any upcoming projects or initiatives that you’re excited about, and how do you see your writing evolving in the future?

I have a new book that I am excited about. It comes out next year. It is a novel without a title, set in Peru and Mexico; written in Spanglish. I will like to talk more about it but nothing more but to say it is about crime and CIA and FBI.