1

LAGOS – Every morning on Nigeria’s highways, thousands of cars, buses, and trucks set off carrying families, traders, and goods. Many arrive safely; some do not. A central but often overlooked reason is that too many vehicles that should have been grounded continue to ply the roads.

Vehicle inspection – the systematic examination of brakes, steering, lights, emissions, and structural soundness – remains one of the most effective tools for reducing mechanical failures and preventing avoidable crashes.

Yet, in Nigeria, the promise of modern, computerised inspection has collided with patchy implementation, uneven standards, and, in many cases, outright corruption. The result is a system that sometimes ensures safety – and sometimes merely produces a certificate.

A System Designed To Protect

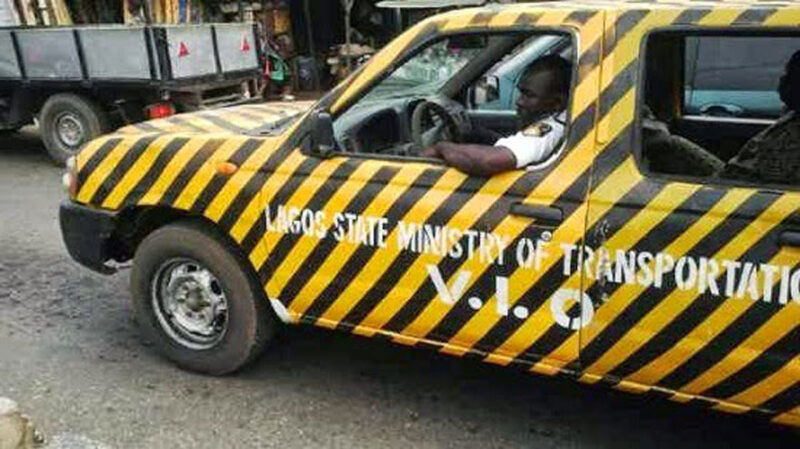

The Vehicle Inspection Service (VIS) – operating at federal and state levels – was established to certify that vehicles meet minimum road-worthiness standards before registration or renewal.

The VIS issues a Road Worthiness Certificate valid for a period of one year from the date of issuance. At the expiration of this period, vehicle owners are required to renew the certificate annually to ensure that their vehicles remain compliant with safety and environmental standards set by the authorities.

While some states may issue temporary certificates valid for six months, particularly for newly registered vehicles, the standard validity period for both private and commercial vehicles remains twelve months.

By standard, renewal is subject to a mandatory inspection process at designated centres to confirm that each vehicle meets the necessary road safety requirements before a new certificate is granted.

Over the past decade, there has been a drive to automate these checks. Computerised centres equipped with diagnostic tools such as brake testers, gas analysers, suspension rigs, and headlamp aligners were introduced to eliminate subjectivity and human interference.

Dr. Yusuf Suberu, who coordinates road safety advocacy activities for the VIS Mayor, as an auxiliary officer, has publicly urged motorists to use these computerised facilities. “Regular vehicle inspection will reduce road crashes,” he said at a recent transport forum, stressing that “many vehicles with mechanical defects ply the roads daily because of poor enforcement and lack of awareness.”

But while technology is spreading, malpractice remains entrenched.

How It’s Bypassed

In Lagos State, the cost of obtaining and renewing a road worthiness certificate varies depending on the vehicle category. Reports indicate that for private vehicles that go through due process, the official renewal fee ranges between N10,000 and N15,000, while commercial vehicles attract higher charges, estimated between N20,000 and N25,000.

However, investigations by Daily Independent reveal that the inspection process, in many centres has been undermined by what insiders call “paper road-worthiness” – certificates issued at exorbitant rates without actual mechanical tests.

In Lagos, two vehicle owners shared their experiences anonymously. One, a commercial driver operating between Ikotun and Oshodi, admitted that he obtains his road-worthiness certificate within a few hours without his vehicle ever entering the inspection bay.

“All I do is meet an agent outside the VIO centre,” he recounted. “He usually tells me not to bother with inspection because it takes days. I always pay about twice the official rate, and within hours, the paper is ready. I have been doing that for over seven years now, and my bus never even entered the compound.”

A second Lagos motorist, a private car owner based in Surulere, echoed a similar story.

“I always try to keep my car in good condition since I bought it. But because having a road-worthiness certificate is mandatory to avoid harassment, I usually renew it before it expires. I have someone at the VIO in Ikeja that helps me to get the certificate because I don’t have time to go join the long queue for inspection. I don’t even know the official rate but I usually pay him a reasonable amount, and by the next day, my certificate is ready,” he said. “I haven’t taken my car for any inspection. Just paperwork.”

In Abuja, where the Federal Capital Territory Directorate of Road Traffic Services (DRTS) operates some of the country’s most modern facilities, one vehicle owner also confessed that the system is not immune.

“I know someone inside the DRTS who helps me process my papers,” said the owner, who drives a 2014 Toyota Corolla. “The official charge might be less but sometimes I pay him N20,000, sometimes N25,000, and he gets the certificate within hours. They don’t even ask for an inspection report. If you want it fast, you pay more; that’s how it works.”

These voices reflect a widespread practice that undermines the very foundation of Nigeria’s road safety regime.

An Insider Speaks: The Abuse From Within

A serving VIS officer in Lagos, who spoke on condition of anonymity, confirmed to Daily Independent that the process has been “deeply compromised” – particularly at inspection centres attached to local government secretariats.

“The truth is that many vehicle owners don’t go through actual inspection anymore,” he revealed. “They prefer to ‘settle’ agents or officers to get the certificate quickly. Top officers in the system know about it and have turned it into a money-making racket.”

He provided a vivid account of how the practice operates at the VIS inspection centre located within the Ikotun Local Government Secretariat.

“At the Ikotun centre, for example, some officers collaborate with touts who approach motorists at the gate,” he explained. “They collect documents, process them internally, and print the certificate without any physical inspection. The money is shared – some to the junior staff, some to senior officers. A vehicle that should go through brake and suspension tests leaves with a clean bill of health on paper. It happens every day.”

The officer said similar cases occur in other centres across the state, especially in overcrowded areas like Ojodu, Badagry, and Mushin.

“When the head office conducts random audits, officers quickly arrange for a few cars to be tested for show, just to pretend that procedures are followed,” he added. “But behind the scenes, most certificates are bought.”

The Numbers Tell Their Own Story

The Federal Road Safety Corps (FRSC) recorded 5,081 road traffic deaths in 2023, a figure that rose to 5,421 in 2024, despite reported decreases in total crash numbers. According to FRSC data, over 20 percent of accidents in 2024 were linked to mechanical faults such as brake failure, burst tyres, and steering problems – faults that standard inspection should have detected.

In the FCT, official data from the Directorate of Road Traffic Services show that 63,256 vehicles were registered, 66,954 revalidated, and 13,716 subjected to inspection in a six-month period. Yet, insiders say a large number of these so-called “inspections” never involved an actual mechanical test.

Across Lagos, official estimates suggest that about 2.1 million vehicles are registered, with roughly 400,000 undergoing “roadworthiness renewal” annually. But with only a handful of fully operational computerised centres – less than 10 in the entire state – experts question how many vehicles can realistically be inspected under existing capacity.

Why It Persists

Investigation reveals that systemic corruption, inadequate infrastructure, and weak enforcement feed the cycle. “The process is designed to be transparent,” said the anonymous VIS official, “but it’s been overtaken by human shortcuts.”

Daily Independent gathered that in Lagos, inspection centres are run in partnership with private operators under the public-private partnership (PPP) model. While the arrangement was meant to ensure efficiency, it has also created opportunities for rent-seeking. Some operators reportedly issue certificates based on record entries rather than physical inspection, especially when pressure mounts to meet revenue targets.

The anonymous Lagos VIS officer confirmed this link:

“The PPP centres are supposed to remit revenue to the state government, so they are under pressure to process as many vehicles as possible. Some staff simply issue certificates to meet targets – the fewer vehicles fail inspection, the more revenue they record.”

Consequences On The Road

The implications are deadly. The FRSC attributes roughly one in five fatal crashes to vehicle defects that could have been detected and fixed during a proper inspection. In one widely reported incident in Ogun State in early 2025, a tanker with faulty brakes overturned on the Sagamu-Benin Expressway, killing six people and injuring nine others. The vehicle’s last inspection certificate had been issued only two weeks earlier.

The findings are alarming – if computerised inspections can be bypassed with cash, the system becomes meaningless. “You can’t rely on paper certificates when lives are at stake,” said the anonymous VIS officer. “It means any car, no matter how dangerous, can be declared roadworthy.”

Calls For Transparency And Reform

Experts argue that fixing the inspection system requires more than machines – it requires integrity, oversight, and digital accountability.

Civil society groups like the Safety Advoc a cy and Empowe rment Foundation (SAEF), a registered non-governmental, not-for-profit organisation based in Lagos, have called for the digitisation of inspection records linked directly to the national vehicle registration database, making it possible to verify the authenticity of any certificate by plate number.

In practice, if each vehicle’s inspection result should be uploaded in real time to a national portal accessible to the FRSC, insurers, and the public, fake certificates will become harder to issue.

Also, linking inspection data to insurance underwriting, would encourage honesty. Insurers could refuse to cover vehicles without verifiable inspection histories, creating an incentive for compliance.

A Matter Of Life And Policy

For many Nigerians, vehicle inspection remains a bureaucratic formality – another stamp to obtain, not a safety requirement. The VIO’s repeated calls for motorists to embrace computerised testing have been drowned by public distrust and cost concerns.

But the evidence is clear: inspection saves lives. As Dr. Suberu once remarked, “Every vehicle that passes inspection genuinely becomes less of a danger to its passengers and others on the road.”

Until that principle becomes reality across Nigeria, thousands of vehicles will continue to bear glossy certificates of road-worthiness – but remain, in truth, potential death traps.

![Olubadan: Nigerians condemn Taye Currency’s song at Ladoja’s coronation [VIDEO]](https://nnu.ng/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Taye-currency-300x250.jpeg)