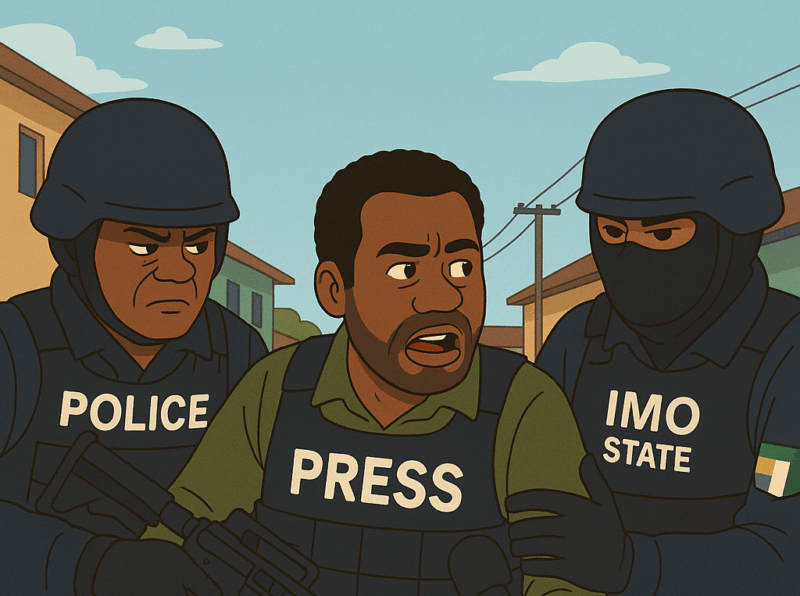

In its 2024 Openness Index, the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) declared Imo State the worst place to be a journalist in Nigeria. The index, a subnational assessment of press freedom and civic space in Nigeria, was published in July. It ranked states based on political openness, media independence, and the safety of civic actors.

The Imo State Government quickly dismissed the report. Commissioner for Information Declan Emelumba described the report as “fraught with fallacies and sensational stunts,” insisting it was “biased, jaundiced, unreliable, and absolutely unempirical.”

But when Martin Opara, editor of the Nigerian Watchdog Newspaper, read the report, he simply smiled, because his organisation had been a victim of targeted harassment and attack by the state government. For him, the CJID report reflected reality, his newspaper having borne the brunt of state hostility.

“Since 2015, our office has been raided more than five times by the police, usually because of publications we released,” Mr Opara told PREMIUM TIMES in late August. “In 2023, our correspondent was banned from covering proceedings at the House of Assembly. They told us outright: ‘We don’t want Watchdog here.”

Unlike many local outlets, Mr Opara said the Nigerian Watchdog Newspaper insists on publishing reports that hold institutions and governments accountable.

That independence has also made them a target. “Independent journalism has become very difficult here,” he lamented. “We face raids, arrests, bans, false accusations, and constant intimidation. But we continue to do our work.”

Press freedom under siege.

The CJID’s index paints a troubling national picture: 48 press freedom violations were recorded between December 2023 and November 2024, mostly perpetrated by security agencies. Police, military, and state security agents were identified as the main culprits in harassing journalists and suppressing dissent.

At the end of the spectrum, Cross River ranked highest for openness, with Ondo, Delta, Katsina, and Ekiti also performing well.

By contrast, the lowest-performing states based on the perception index are Anambra, Nasarawa, Bauchi, Ebonyi, and Imo, with Imo sitting at the bottom.

The index evaluates states across seven factors: political environment, legal framework, economic pressures, socio-cultural context, journalistic principles, treatment of journalists, and gender inclusion.

Press freedom advocate Stephanie Adams-Douglas told PREMIUM TIMES that arbitrary arrests, assaults, and lawsuits targeting journalists violate constitutional rights. “When accountability is absent for these violations, it leads to a deterioration of the system, ultimately undermining integrity and truth in the media,” she said.

She added: “This entails ensuring that perpetrators who commit acts of violence or intimidation against journalists are held accountable.”

Inside Imo: “They threatened to kill me”

For Anslem Anokwute, the findings in CJID’s report are not abstract metrics. They are his lived experiences. Mr Anokwute had worked with several newspapers, including Watchdog Newspaper, before floating an online outfit, Otikpu Newspaper.

On 17 June, he published a report detailing how the governor’s aide on Monitoring and Compliance, Chinasa Nwaneri, allegedly usurped the Ministries of Lands and Transport roles by issuing directives under his own name.

“After the story went viral, on July 10th, he threatened me openly, saying he would send boys to my house and have me bundled away,” Mr Anokwute recalled. “Colleagues called to warn me, but I wasn’t afraid. I only reported the truth.”

The backlash was immediate. The report was republished by several online platforms, casting the conflict as government hostility toward journalists. Amid mounting pressure, Mr Nwaneri backed off, but the threat lingered.

“Because of the backlash, people started calling the governor’s aide from different corners. Since then, he has avoided confrontation with me, but I know the matter isn’t settled,” Mr Anokwute said.

“I even met the commissioner of police, who advised me to file a petition. I told him I would wait until the threats turned into action,” he said.

On the state of press freedom in the south-eastern state, Mr Anokwute’s conclusion is blunt: “There is no real press freedom in Imo. When journalists are arrested, threatened, or told they will be killed, what freedom exists?”

Since 2020, Mr Anokwute added, appointees have been under strict orders not to grant interviews to journalists.

“Even commissioners speak off the record and beg us not to quote them. They are afraid of sanctions.”

“Today, threats come directly from the state government (Imo),” he said, adding that “Under former governor Rochas Okorocha, even when we criticised him, he told us: ‘Use my name, make your money, just tell the truth.’ But this administration is different.”

Assaulted, sued, and silenced

Physical assault and lawsuits are also common weapons against journalists in Imo.

In January 2024, a journalist working with Newsbreak Newspaper, Kelechi Ugo, was attacked while investigating allegations against Rosemary Izuogu, the former chairperson of the state’s Local Government Service Commission.

“We learned her son assaulted a staff member,” Mr Ugo explained. “At the hospital, I photographed the victim. When I went to Mrs Izuogu’s office for her side of the story, she claimed it was a private office and ordered me out. Then her son physically assaulted me, saying journalists had no right to be there.”

Despite the assault, Mr Ugo filed his report. But instead of accountability, the official sued the publishing newspaper in court. The case remains pending in court.

“As journalists, we only have our pens. We don’t have guns,” Mr Ugo said. “Yet when we do our job, they sue us to silence us.”

The Nigerian Watchdog is also battling lawsuits filed by political figures over its reports.

Its editor, Mr Opara, told PREMIUM TIMES that Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) are increasingly deployed to drain media houses financially and intimidate reporters.

Precious Nwadike, publisher of the Nigeria Watchdog Newspaper, corroborated this account, saying press freedom is entirely absent in Imo State.

Mr Nwadike recalled that in 2015, he was arrested and detained for his story, which exposed how a cook attached to Uche Nwosu, the chief of staff to then-governor of Imo State, Rochas Okorocha, allegedly stole a huge sum of money.

“The matter lasted four years from 2015 to 2019,” he told PREMIUM TIMES.

The journalist maintained that the frequent attacks, arrests and litigations against reporters blur claims of press freedom in Imo State.

“If for any reason a journalist holds the government accountable, or questions their programmes and activities, you have become an enemy of the government,” Mr Nwadike said, noting that the Nigerian Watchdog and its journalists have become targets of sundry lawsuits in such instances.

“Frightening degree of intolerance”

A human rights lawyer, Inibehe Effiong, told PREMIUM TIMES that the solution to frequent harassment, police invitations, and lawsuits against journalists is for journalists to intensify “factual” reporting to expose society’s ills.

Mr Effiong said harassment and lawsuits persist primarily due to ignorance of the law.

“Under the Cybercrimes Act as amended, it is no longer permissible to arrest journalists based on publications they have made which someone finds offensive or defamatory,” he said.

“The continued reliance on the Cybercrimes Act by the police and other persons; they’re completely ignorant and misguided.”

In the case of Imo State, Mr Effiong argued that Governor Uzodinma has demonstrated a “frightening degree of intolerance” against dissenting views, citing the case of a lawyer in the state recently invited by the police for criticising the governor.

Threats before publication

The intimidation sometimes begins before a story is even published.

Mr Opara of the Nigeria Watchdog recounted texting the official involved to get her response while investigating alleged corruption in the education ministry.

“Instead of replying, she accused me of trying to bargain with her,” he said. “Then I received a call from Ferdinand Uzodinma, the governor’s brother and deputy chief of staff. He asked me to drop the story. When I refused, he invited me to Government House. A contact later warned me it was a trap, that I would have been picked up at the gate without a record of my visit, and they would sue me.”

“These are the kinds of pressures we face,” Mr Opara said. “Despite the intimidation, I plan to publish my report with evidence to back it up.”

“Nobody treats us as human beings”

For many Imo journalists, the hostility goes beyond official circles.

Nkechi Ojukwu, a journalist with Newspoint Newspaper, lamented: “It’s a horrible situation in Imo State. Nobody treats us as human beings. We are the fourth estate of the realm, recognised by the constitution, yet people treat us like we are nobody (in Imo State). We are the watchdog of society.”

Although security operatives have not arrested Ms Ojukwu, the fact that some of her colleagues have been detained and intimidated raises concerns.

Curiously, journalists working for state-owned media organisations in Imo State also battled restricted access to information.

Charles Nnaji (not his real name), a journalist with the state-owned Statesman Newspaper, told PREMIUM TIMES in August that the state government had been “very unfriendly” to journalists.

Mr Nnaji said the government uses a “divide and rule” style by choosing to work with a few journalists who produce reports that are “favourable” to them while fighting others who try to hold them accountable.

He added that he has not suffered any attacks because he does not do “critical reports” against the government, considering that he works for them.

Mr Nnaji said even community members and non-state actors contribute to making the environment hostile for journalists.

“You can’t boldly identify as a journalist anymore, especially if you do investigative work,” Mr Nnaji said.

“Here in Imo State, the environment is hostile (for journalists who do critical reports) not only from the government but even from private individuals in communities.”

Fighting repression

In response to mounting threats and intimidation, some journalists formed the Association of Imo-Based Journalists, led by Mr Ugo.

“All those harassed usually run to me. We defend them,” he said.

When the governor’s aide threatened Mr Anokwute, the association rallied behind the journalist. “We issued a press release defending him. If we hadn’t, I don’t know what would have happened.”

The group has documented several cases of police brutality against journalists and instances where reporters were barred from covering public events. “Journalism in Imo is a herculean task,” Mr Ugo said.

Arrests on repeat

Beyond harassment and lawsuits, arrests are frequent.

In July 2023, broadcaster Chinonso Uba, popularly known as Nonso Nkwa, was arrested after anchoring his morning programme on Ozisa FM, a privately owned radio station in Owerri, the capital of Imo State.

Mr Uba’s arrest was based on allegations of cyberstalking, character defamation, and misinformation. Police claimed they had clips proving his offences.

An FCT high court later ordered his release after one month in detention.

“They (Imo State Government) said I committed cybercrime against the governor (Gov Uzodinma) by saying that the governor brought in Ebubeagu in Imo to kill Imo people and youths,” he told PREMIUM TIMES.

Ebubeagu is a security outfit created by the Imo State Government. But the outfit has repeatedly been accused of extrajudicial killings, torture, extortion and other crimes.

“The case is still in court till now,” Mr Uba told PREMIUM TIMES. The journalist later faced a fresh arrest in 2024, again on allegations of defamation.

“On October 20, 2024, I was arrested again by the government of Imo State and taken to a magistrate court that works with the government, and the court remanded me in prison after charging me with treasonable felony, arson, terrorism and others,” he said.

Mr Uba recalled that the charges against him followed his criticism of the alleged planned establishment of an Internally Displaced Persons Camp for people from northern Nigeria in the Nsu community in Ehime Mbano LGA.

“I spent two months in prison before I was finally released by the court,” he said, pointing out that the case later died because the charges could not be proved.

In mid-September, the journalist was invited by the police in Imo State after uploading a video clip on a Facebook page which showed police operatives were allegedly colluding with others to carry out illegal organ harvesting in the state.

“I will be going to the police today with one or two victims of organ harvesting. I will meet with the Commissioner of Police today (22 September 2025),” he said. “From 2020 till date, we have had a very terrible suppression of freedom of expression and fundamental human rights of Imo people by the government of Hope Uzodinma.”

Imo State officials continue to deny responsibility for these attacks.

But the verdict is clear for journalists working on the ground: in Imo, accountability journalism has become a perilous occupation.

Angela Nkwo-Okpolu, a journalist with Leadership Newspaper, practised journalism in Lagos State for years before relocating to Imo State in 2015.

Mrs Nkwo-Akpolu told PREMIUM TIMES that, unlike in Lagos, journalists in Imo State face heavy intimidation and suppression.

“Well, in Lagos, you do your report, maybe you can only be lobbied to drop a report, unlike in Imo State, where it is outright intimidation (of journalists),” she said.

The journalist said Imo government officials often refuse to respond to enquiries by reporters or, at best, ask you to contact the governor himself.

“But it is a near impossibility,” she said of having an audience with the governor.

She said there was access to information in Imo State before now, particularly during the administration of Rochas Olorocha, who governed the state from 2011 to 2019.

“Access to government officials under the Okorocha administration was better. They could play pranks, but in the end, you would get what you wanted. But no intimidation or prosecution (of journalists),” Mrs Nkwo-Akpolu recalled.

She suggested that press freedom in Imo State worsened under Mr Uzodinma’s administration, which came on board on 14 January 2020 after the Supreme Court nullified the election of the then-Governor of the state, Emeka Ihedioha of the Peoples Democratic Party.

Meanwhile, besides Mr Uba and Mrs Nkwo-Akpolu, no journalist interviewed for this report participated in the CJID survey. This shows that more journalists in the state shared similar views as Mr Uba and Mrs Nkwo-Akpolu.

Attacks, arrests, lawsuits against journalists in Nigeria

Journalists continue to battle attacks, arrests and lawsuits in many parts of Nigeria for simply carrying out their constitutional duties of holding institutions and governments accountable.

The 2025 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders (RSF) listed Nigeria as one of West Africa’s “most dangerous and difficult countries for journalists.”

Nigeria ranked 122nd out of 180 countries in the index. In 2024, the country ranked better in the press freedom index, emerging 112th out of 180 countries.

The RSF noted in the 2025 index that Nigerian journalists “are regularly monitored, attacked and arbitrarily arrested.”

According to a report by Media Rights Agenda (MRA), between May 2023 and May 2025, for instance, there were at least 141 incidents of attacks on journalists, media workers, and ordinary citizens for expressing their views on various issues, including governance, economic hardship, and the security situation in Nigeria.

The MRA earlier reported that between 1 January and 31 October 2024, there were 69 attacks, of which security agencies (police, military, intelligence) were responsible for 45, representing 65 per cent of the total attacks.

Some of the attacks against journalists, the group noted, occurred in the form of unlawful arrests and detention, physical assault, threats to life, raids on homes/offices, abduction, obstruction from reporting, harassment, and intimidation.

Similarly, a 2023 survey by the International Centre for Investigative Reporting found that within 12 months, 40 organisations, including media organisations, journalists, and civic advocates, faced frivolous lawsuits for reporting or advocating about issues of public concern.

READ ALSO: Israel strikes Gaza hospital, kills another five Palestinian journalists

The survey, with 141 respondents, further showed that some of these affected organisations received up to 10 lawsuits within one year, which often require the organisations or journalists to either reveal their source of information, retract a published report, or pay a ‘damage fee’ running into millions of Naira.

One of the Nigerian laws often used to harass and prosecute journalists is the Cybercrimes (Prohibition, Prevention) Act.

First enacted in 2015, the Act was later amended in 2024 after heavy criticism for suppressing free speech and dissent, mainly through its vague sections like Section 24, which had been used against journalists and activists for online statements deemed “false” or “insulting.”

According to a report by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), at least 29 journalists had faced prosecution under the Act before its amendment.

The CPJ further observed that despite the amendments, journalists have continued to be targeted for publishing news in the public interest.

The group had earlier documented at least 24 journalists killed in Nigeria between 1992 and 2023, many of them in connection with their reporting.

Government response

When PREMIUM TIMES contacted Imo’s Information Commissioner, Declan Emelumba, he dismissed most accounts.

Mr Emelumba later demanded the names of the journalists and specific cases of harassment, arrest, and lawsuits against the journalists in the state, all of which were supplied to him.

“Most of those are from local newspapers. You didn’t speak to journalists from national newspapers with credibility,” he said.

The commissioner did not respond directly when asked if he categorised the individuals as non-journalists because they do not work in national newspapers.

When provided with the name of a journalist working with a national newspaper, Mr Emelumba claimed that he was unaware of harassment, arrest, threat, or charges against the journalist and others in the state.

Even when provided with specific cases and the government officials involved, the commissioner argued that the officials might have had “personal issues” with the affected journalists and could not have been carrying out such assignments on behalf of the state government.

“I don’t know them,” Mr Emelumba said when provided with the names of journalists who had suffered harassment, arrests, or litigation in the state.

When pressed on lawsuits filed by government officials, he responded:

“If somebody believes he was defamed and goes to court, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. The court is the due process for settling issues.”

Regarding lack of access to information, Mr Emelumba claimed state government officials make information available to “only recognised and accredited journalists.”