President Trump very recently signed into law a sweeping budget reconciliation bill that includes an interesting measure: a levy on remittances sent from the United States (U.S.) by non-nationals to their home countries. Framed by its proponents as an innovative way to shore up domestic revenue and reduce budget deficits, this new excise tax imposes an additional 1 per cent on money transfers, meaning roughly $3.50 out of every $100 sent from the U.S. will now be lost to taxation. Yet when viewed through the lens of business ethics, the policy’s shortcomings become painfully clear. It reveals an ethical blind spot in fiscal policymaking that fails to account for fairness, social responsibility, and the broader network of stakeholders affected by such decisions.

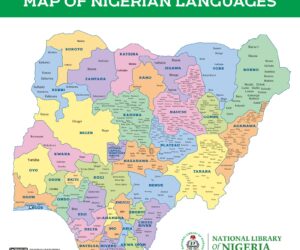

Remittances are far from luxuries. They are lifelines for millions of households across Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2023 alone, the region received over $54 billion in remittances, exceeding official development assistance and often surpassing foreign direct investment. For countries like Nigeria, Ghana, Kenya, and Senegal, these funds cover essentials such as food, housing, healthcare, and education. In smaller economies like Liberia and The Gambia, remittances account for more than 6 percent of GDP. From a business ethics standpoint, targeting such flows with an additional tax is deeply problematic. U.S. non-nationals typically remit not from surplus wealth but from a sense of obligation and compassion, a profound ethical responsibility to family and community. By taxing these acts, the policy effectively penalises virtue, undermining the core ethical principles of solidarity and justice. While the tax appears to target senders who are often low-income immigrants working in agriculture, domestic care, and sanitation, the real burden falls squarely on recipients: elderly parents, children, and extended families who depend on these funds for survival. This contradicts the ethical principle of fairness, which holds that the weakest stakeholders should not disproportionately bear the cost of policy decisions. From a business perspective, it mirrors the classic trap of seeking short-term gains at the expense of long-term stakeholder value. While the United States may collect some additional revenue in the short term, the broader social and economic harms risk undermining trust, stability, and goodwill across entire communities and regions.

Read also: Nigerians, others to be affected as US plans 5% tax on remittances

Crucially, the measure neglects the broader network of stakeholders involved. Remittances are not merely financial transactions; they are social contracts that bind diaspora communities to their countries of origin. By imposing extra costs, U.S. policymakers send a troubling message that short-term domestic gains matter more than shared global responsibility. This approach runs counter to the ideals of ethical globalisation, which call on nations, particularly wealthy ones, to act responsibly beyond their own borders. As ethicist Thomas Donaldson has argued, ethical obligations do not end at a nation’s shores. The United States benefits greatly from immigrant labour that supports its economy, yet it now proposes to burden the very communities those workers sustain. In diplomatic terms, this policy risks straining longstanding trade, security, and development partnerships between the U.S. and African nations. It threatens to reinforce exploitative global patterns where wealthier countries prosper from migration, only to extract more value through taxation at the expense of the vulnerable. Beyond the moral questions, there are significant practical risks. By making formal remittance channels more expensive, the tax could push migrants toward informal, unregulated methods of sending money, such as cash couriers or hawala systems. This not only undermines financial transparency but also exposes families to fraud and other risks. Moreover, by destabilising remittance-dependent economies, the policy could deepen aid dependency, drive up irregular migration, and even provoke social unrest. These are real-world consequences that a narrow, revenue-focused policy fails to consider.

For African nations, this development should serve as a wake-up call to reduce overreliance on remittances. Governments must invest in regional economic resilience and support alternative channels, including regulated fintech and cryptocurrency solutions, to reduce exposure to external policy shocks. Encouraging formal remittance platforms can also help protect diaspora contributions and transform them into sustainable investments in infrastructure, education, and entrepreneurship. Regional bodies like the African Union, ECOWAS, and SADC should intensify diplomatic engagement with United States lawmakers, civil society, and business groups to highlight the ethical and economic harms of the policy.

While the remittance tax may appear fiscally pragmatic on paper, it remains ethically flawed. It prioritises narrow national interests over principles of equity, solidarity, and global interdependence. Every remittance represents a story of sacrifice, hope, and responsibility across borders. True ethical governance must blend fiscal responsibility with moral clarity, ensuring policies do not punish those who give the most from the least. In the end, ethical policymaking requires more than economic calculation; it demands compassion, foresight, and respect for our shared humanity. Anything less risks turning fiscal policy into a tool of injustice rather than progress.

Chinedu Okoro is the Centre Manager of the Christopher Kolade Centre for Research in Leadership and Ethics (CKCRLE), Lagos Business School. Contact: [email protected]

Emmanuel Orakwe is a doctoral student in development studies and a research assistant at the Christopher Kolade Centre for Research in Leadership and Ethics (CKCRLE), Lagos Business School.